LONDON: As congratulations flooded into London this week from heads of state around the world, two messages in particular served as reminders of the special relationship that has flourished between the Saudi and British royal families throughout the 70-year reign of Queen Elizabeth II.

Behind the formality of the cables sent by King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, wishing her “sincere felicitations and best health and happiness” on the occasion of her platinum jubilee, is a history of friendship dating back to the earliest days of her reign, which began on Feb. 6, 1952.

That day, her father King George VI died while the 25-year-old Elizabeth and her husband Philip, duke of Edinburgh, were in Kenya on a tour of Africa.

Having left England a princess, she flew home in mourning as Queen Elizabeth II. Her coronation took place on June 2 the following year.

Among the guests at the coronation were members of four royal families from the Gulf: The rulers or their representatives of the then-British protectorates of Bahrain, Kuwait and Qatar, and Prince Fahd bin Abdulaziz, representing the 78-year-old King Abdulaziz, Saudi Arabia’s founder and first monarch, who had only five months left to live.

The bonds between the Saudi and British monarchies cannot be measured by the frequency of formal occasions alone, although an examination of the record of state visits held by Buckingham Palace reveals an illuminating distinction.

Since the queen succeeded her father, there have been no fewer than four state visits to Britain by Saudi monarchs, a number matched by only four other countries, including the UK’s near-neighbors France and Germany.

The first to travel to London was King Faisal, greeted with all the pomp and ceremony of a full British state welcome at the start of his eight-day visit in May 1967.

Queen Elizabeth II speaks with Emirati Minister of State Reem al-Hashemi during a visit to the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi on Nov.24, 2010. (WAM via AFP)

Met by the queen, members of the British royal family and leading politicians — including then-Prime Minister Harold Wilson — King Faisal rode to Buckingham Palace with Elizabeth and Philip in an open horse-drawn state carriage, drawn through London streets lined with cheering crowds.

During a busy eight-day schedule, the king found time to visit and pray at London’s Islamic Cultural Centre.

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II with Saudi Arabia’s King Khaled in 1981. (AFP/Getty Images)

His son Prince Bandar, who that year graduated from the Royal Air Force College Cranwell, deputized for his father on a visit to inspect English Electric Lightning fighter jets being readied for shipment to Saudi Arabia. Later, the prince would fly Lightnings as a fighter pilot in the Royal Saudi Air Force.

King Faisal was followed on state visits to Britain by his successors King Khaled in 1981, King Fahd in 1987 and King Abdullah in 2007.

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II with Saudi Arabia’s King Fahd in 1987. (AFP/Getty Images)

In February 1979, traveling on board the supersonic jet Concorde, Queen Elizabeth visited Riyadh and Dhahran during a Gulf tour that also took her to Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the UAE and Oman.

In Saudi Arabia, she was hosted by King Khaled and enjoyed a series of events, including a desert picnic and a state dinner at Maathar Palace in Riyadh.

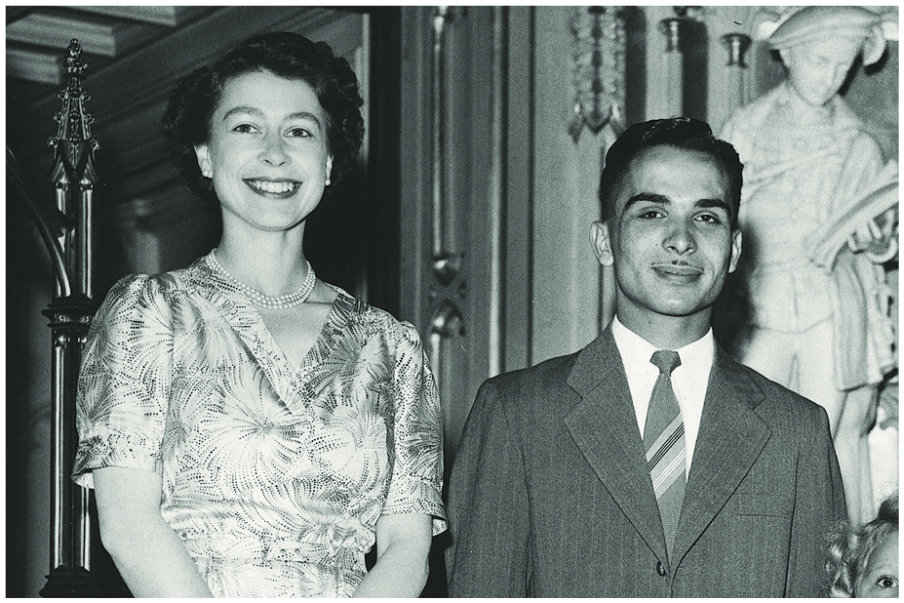

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II with King Hussein of Jordan in 1955. (AFP/Getty Images)

In return, she and her husband hosted a dinner for the Saudi royal family on board Her Majesty’s Yacht Britannia.

Poignantly, Britannia would return to the Gulf one last time, in January 1997, during its last tour before the royal yacht was decommissioned in December that year.

However, the relationship between the two royal families has not been limited to the great occasions of state.

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II with Oman’s Sultan Qaboos bin Said in 2010. (AFP/Getty Images)

Analysis of the regular Court Circular published by Buckingham Palace shows that members of Britain’s royal family met with Gulf monarchs more than 200 times between 2011 and 2021 alone — equivalent to once a fortnight. Forty of these informal meetings were with members of the House of Saud.

Most recently, in March 2018, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman had a private audience as well as lunch with the queen at Buckingham Palace.

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II with Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in 2018. (AFP/Getty Images)

Later, he dined with the prince of Wales and the duke of Cambridge during a visit to the UK that included meetings with then-Prime Minister Theresa May and Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson.

Serious topics, such as trade and defense agreements, are often the subjects of such meetings. But good-natured fun, rather than stiff formality, is frequently the hallmark of private gatherings between the royal families, as Sir Sherard Cowper-Coles, the British ambassador to Saudi Arabia from 2003 to 2006, would later recall.

In 2003, Crown Prince Abdullah, Saudi Arabia’s future king, was a guest of the queen at Balmoral Castle, her estate in Scotland.

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II with Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah in 2007. (AFP/Getty Images)

It was his first visit to Balmoral and, happily accepting an invitation to be taken on a tour of the large estate, he climbed into the passenger seat of a Land Rover, only to discover that his driver and guide was to be the queen herself.

Having served during the Second World War as an army driver, she has always driven herself at Balmoral, where locals are used to seeing her out and about behind the wheel of one of her beloved Land Rovers.

She is also known for having great fun at the expense of guests as she hurtles one of the vehicles along the narrow lanes and across the rugged terrain of the estate.

Queen Elizabeth (2nd R) and Prince Philip (L) receive Qatar's Emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani (R) and his wife Sheikha Mozah bint Nasser at Windsor Castle on Oct. 26, 2010. (AFP)

By Sir Sherard’s account, Prince Abdullah took the impromptu fairground ride well, although at one point, “through his interpreter,” he felt obliged to “implore the queen to slow down and concentrate on the road ahead.”

Aside from the commonality of their royalty, the queen and the monarchs of the Gulf have always bonded over their mutual love of horses, a shared interest that dates back to at least 1937, when Elizabeth was an 11-year-old princess.

To mark the occasion of her father’s coronation that year, King Abdulaziz presented King George VI with an Arabian mare.

A life-size bronze statue of the horse, Turfa, was unveiled in 2020 at the Arabian Horse Museum in Diriyah, where it has pride of place today.

At the time of the unveiling, Richard Oppenheim, then-Britain’s deputy ambassador to Saudi Arabia, highlighted how the two royal families had always bonded over this common interest.

“The queen has many horses, and King Salman and the Saudi royal family also have a long-held love of horses,” he said.

The queen also shares that love with Sheikh Mohammed Al-Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai and vice president of the UAE, who owns the internationally renowned Godolphin horse-racing stables and stud farm in Newmarket, the home of British horse racing.

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II with Dubai’s Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al-Maktoum in 2010. (AFP/Getty Images)

The two have often been seen together at great events on the horse-racing calendar, such as the annual five-day Royal Ascot meeting, regarded as the jewel in the crown of the British social season, which this year runs from June 14-18.

Team Godolphin has had several winners at Royal Ascot, where the queen’s horses have won over 70 races since her coronation.

Britain's Queen Elizabeth with the Emir of Kuwait, Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah. (AFP)

This weekend, as flags fly from homes and public buildings, thousands of events are taking place across Britain to mark her platinum jubilee, including street parties; the traditional Trooping the Colour at the Horse Guards Parade; gun salutes; a fly-past by the Royal Air Force, watched by the queen from the balcony of Buckingham Palace; and the lighting of more than 3,000 beacons nationwide.

At the age of 96, Elizabeth — queen of the UK and the Commonwealth, and monarch to more than 150 million people — has reached a royal milestone rare not only in Britain, but across the world.

By Friday, she will have reigned for 70 years and 117 days, putting her within nine days of becoming the second-longest-serving monarch in world history.

Bhumibol Adulyadej, king of Thailand from 1946 until his death in 2016 at the age of 88, ruled for 70 years and 126 days.

Only Louis XIV of France was on the throne for longer, ruling between 1643 and 1715, for 72 years and 110 days.

The secret to Elizabeth’s longevity, perhaps, lies in the words of the British national anthem “God Save the Queen,” which will be sung heartily at events across the UK this weekend: “Long live our noble queen … Happy and glorious, long to reign over us, God save the queen.”