DUBAI: A day before the second anniversary of the Aug. 4, 2020, Beirut port blast, the World Bank published a scathing report on Lebanon’s financial crisis and alleged acts of deception that appear to have made the country’s economic collapse inevitable.

Entitled “Ponzi Finance?,” the report compares the Mediterranean country’s economic model since 1993 to a Ponzi scheme — an investment fraud named after Italian swindler and con artist Carlo Ponzi.

During the 1920s, Ponzi promised investors a 50 percent return within a few months for what he claimed was an investment in international mail coupons. Ponzi then used the funds from new investors to pay fake “returns” to earlier investors.

The World Bank report claims a similar act of deception has taken place in Lebanon since the end of the civil war, whereby public finance has been used for the capture of the country’s resources, “serving the interests of an entrenched political economy, which instrumentalized state institutions using fiscal and economic tools.”

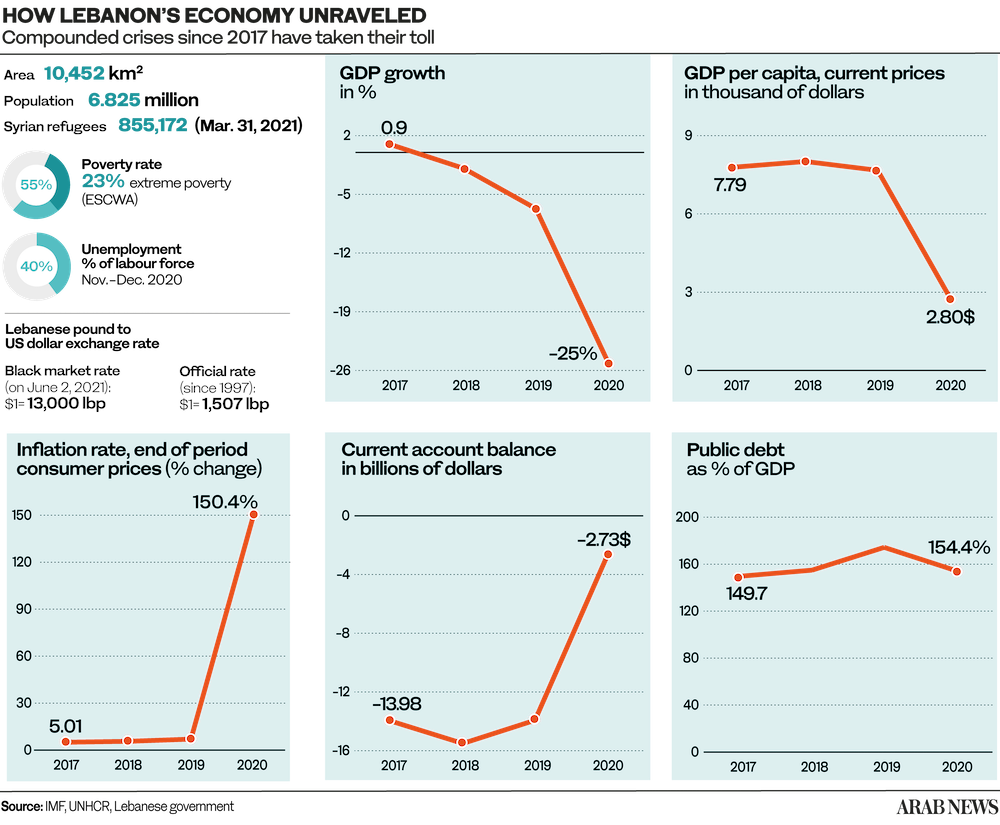

The report says excessive debt accumulation has been used to give the illusion of stability and to reinforce confidence in the economy so that commercial bank deposits keep flowing in. The study analyzes Lebanon’s “public finances over a long horizon to understand the roots of the fiscal profligacy and its eventual insolvency.”

At the same time, according to the report, there has been a “conscious effort” to weaken public-service delivery to benefit the very few at the expense of the Lebanese people. As a result, citizens end up paying double while receiving low-quality services.

The World Bank experts who wrote the report describe Lebanon’s financial crisis as “a deliberate depression” because “a significant portion of people’s savings in the form of deposits at commercial banks have been misused and misspent” over the past 30 years.

“It is important for the Lebanese people to realize that central features of the post-civil war economy — the economy of Lebanon’s Second Republic — are gone, never to return. It is also important for them to know that this has been deliberate.”

A protester stands with a Lebanese national flag during clashes with army and security forces near the Lebanese parliament headquarters in the centre of the capital Beirut on August 4, 2021, on the first anniversary of the blast that ravaged the port and the city. (AFP/File Photo)

The report adds: “These are earnings by expats who toil in foreign lands; they are retirement funds for citizens and perhaps the sole resource for a dignified living; they are necessary financing for essential medical and education services that consecutive governments have failed to provide; they are funds to pay for electricity in light of colossal failures in Electricite du Liban.”

Since 2019, Lebanon has been in the throes of its worst ever financial crisis, which has been compounded by the economic strain of the COVID-19 pandemic and the nation’s political paralysis.

In October 2019, the Lebanese took to the streets in the short-lived “thawra,” or revolution, demanding political and economic change. Their hopes were soon crushed by the trauma of the Beirut port blast, which on Aug. 4, 2020, killed 218 people, injured 7,000, and left 300,000 homeless.

These overlapping crises have sent thousands of young Lebanese abroad to search for security and opportunity, including many of the country’s top medical professionals and educators.

A World bank review of Lebanon's public finances has blamed an entrenched political elite for the economic collapse plaguing the country. (AFP)

Lebanese economists and financial analysts largely agree with the World Bank’s Ponzi scheme analogy.

“Lebanon is the greatest Ponzi scheme in economic history,” Nasser Saidi, a Lebanese politician and economist who served as minister of economy and industry and vice governor for the Lebanese central bank, told Arab News.

Unlike financial crises elsewhere in the world through history, Saidi said the cause of Lebanon’s woes could not be pinned to any single calamity that was outside the government’s control.

Unlike financial crises elsewhere in the world through history, Saidi said the cause of Lebanon’s woes could not be pinned to any single calamity that was outside the government’s control.

“In Lebanon’s case it was not due to an actual disaster, not due to a sharp drop in export prices in commodities, it is effectively man-made.

“The World Bank talks about Ponzi finance, and they are right to point to the fact that you have two deficits over several decades. One was a fiscal deficit brought on by continued spending by the government more than revenues.

“The problem was that the government’s spending did not go for productive purposes. It did not go for investment in infrastructure or to build up human capital. It went for current spending. So, you didn’t build up any real assets. You had a buildup of debt, but you didn’t build up assets in proportion or to compare to the borrowing that you had.”

Since the end of the civil war, Lebanon should have been undergoing a period of reconstruction. However, spending on such infrastructure projects remained low, with the money seemingly siphoned off elsewhere.

“The infrastructure that was required — electricity, water, waste management, transport, and airport restructuring — was neglected,” said Saidi.

A Lebanese activist displays mock banknotes called “Lollars” (top) for a 100 USD bill, in front of a fake ATM during a stunt to denounce the high-level corruption that wrecked the country in Beirut on May 13, 2022. (AFP)

But it was not just material infrastructure of this kind that was neglected. Institutions that would have improved and solidified governance, accountability, and inclusiveness were also ignored, leaving the system vulnerable to abuse.

“Whenever you go through a civil war, you need to think about the causes of the war, and much of it was due to dysfunctional politics, political fragmentation, and the break-up of state institutions,” said Saidi.

“There was no rebuilding of state institutions and because of that, budget deficits continued, and a very corrupt political class began owning the state. They went into state-owned enterprises and government-related enterprises and considered that all state assets are their possessions and instead of possessions of the state.”

Lebanon’s “Ponzi scheme” was also driven by current account deficits and the overvalued exchange rate caused by the central bank policy of maintaining fixed rates against the dollar.

In economics, said Saidi, this is what you called the “impossible trinity,” meaning that a state could not simultaneously have fixed exchange rates, free capital movements, and independence of monetary policy.

The portside blast of haphazardly stored ammonium nitrate, one of the biggest non-nuclear explosions ever, killed more than 200 people, wounded thousands more and decimated vast areas of the capital. (AFP/File Photo)

“If you peg your exchange rate, you no longer have any freedom of monetary policy. Lebanon’s central bank tried to defy the impossible trinity and tried to maintain an independent monetary policy at a time in which the exchange rate was becoming more and more over-valued.”

The Lebanese central bank increased borrowing in an attempt to protect the currency and, in 2015, bailed out the banking system, all the while insisting the system was sound and suppressing IMF reports claiming otherwise.

“The World Bank report states things that we have all been saying since the beginning of the crisis,” Adel Afiouni, Lebanon’s former minister for investments and technology, told Arab News.

“Of course, the crisis was predictable. The indicators were there for years. The debt to GDP level and the unsustainability of this debt to GDP level and the unsustainable deficit that kept growing, and the way (the central bank) has managed public finances in an irresponsible way was a red flag for years.

“Countries usually react in a responsible way by announcing a set of measures to control public finance to reduce the deficit and the debt. This did not happen in Lebanon. The current authorities have ignored basic principles of how to avoid a crisis pre-2019 and how to manage a crisis post-2019.”

In April 2022, Lebanon reached a draft funding deal with the IMF that would grant the equivalent of around $3 billion over a 46-month extended fund facility in exchange for a batch of economic reforms. However, in June, the Association of Banks in Lebanon called the IMF draft agreement “unlawful,” stalling the process.

“This is the first step that should have happened in the first few weeks of the crisis, not two and a half years later,” said Afiouni. “Yet we still need to see radical reforms before we see the funding, and there is no indication now that we are about to see serious implementation of those reforms.”

The World Bank report calls for a comprehensive program of macro-economic, financial, and sector reforms that prioritize governance, accountability, and inclusiveness. It says the earlier these reforms are initiated, the less painful the recovery will be for the Lebanese people. But it will not happen overnight.

“Even if the reforms and laws were passed, it will take time to recover and to restore trust,” said Saidi. “Trust in the banking system, in the state, and in the central bank has been destroyed. Until that trust is rebuilt, Lebanon will not be able to attract investment and it will not be able to attract aid from the rest of the world.”

And although Lebanon held elections in May, propelling several anti-corruption independents to parliament, Saidi doubted their influence would be enough to drive change.

“Some 13 new deputies entered parliament, but they are unlikely to make the changes that are required,” he said. “Politically, business continues as usual. There is a complete denial of reality.”