KARACHI: Pakistani director Seemab Gul is eyeing an Oscar after her short film, ‘Sandstorm’ (Mulaqat), won big at Oscar-qualifying festivals, HollyShorts and the Flickers Rhode Island International Film Festival (RIIFF) 2022.

HollyShorts is an annual independent short film festival that ran from August 11 till August 20, 2022, in Hollywood, California. ‘Sandstorm’ (Mulaqat in Urdu) emerged as one of the top three winners at the festival on Saturday (August 20).

Prior to this, the short film, written and directed by London-based filmmaker Gul, won the Best Live Action title at RIIFF 2022.

The film revolves around a schoolgirl in Pakistan’s southern port city of Karachi, who shares a dance video with a boy she meets online. The film takes a sinister turn when the boy blackmails her with the video.

“It is wonderful to represent Pakistan and most importantly, a female story from the female perspective, which is actually rare in the mainstream industry,” Gul told Arab News in a telephonic conversation on Tuesday.

Gul said she is now eyeing the Oscars shortlist, for which only 10 films will be selected by the end of January. Out of these 10, only five are nominated for the award.

“Only around 200 films from the win at one of these Oscar qualifying festivals are eligible to apply for the Oscars formally,” she explained.

In another still, from Sandstorm, a perplexed Zara sits in an empty classroom. (Supplied)

Sandstorm had its world premiere at the 78th edition of the Venice Film Festival organized by the international art exhibition La Biennale di Venezia, in September 2021. Since then, the film has made it to the world’s most prestigious film festivals, including the Sundance Film Festival and Ischia Film Festival (IFF) in 2022, where it bagged three trophies.

“It does feel great that Sandstorm has been to now nearly 50 festivals worldwide, many of them really recognized and old festivals,” Gul said.

“It is been a great privilege to know that my story resonates. And yes, it is a proud moment to even hear Urdu on the big screen in so many different places,” she added.

Gul said she wanted to explore the dangers that Muslim girls face because “it’s not just the stigma that everyone faces around the world.”

“Girls in Pakistan, for example, have more restrictions on who they can meet, what they can share and whether dancing is at all acceptable in public spaces,” Gul explained.

“So, I wanted to explore the conflict between the desire to meet a partner and desire in general in girls and then all the societal constraints that are up against them when something could go wrong,” she added.

The director said Sandstorm is inspired by a true story that she heard about an Egyptian girl who was shamed online after her video was leaked by a male friend.

Gul was doubtful at first that the short film would resonate with audiences around the world but said she was pleasantly surprised to find people even in progressive Western countries such as France, Canada and the US, had “widely accepted” the movie.

“Ultimately, it is not about what you reveal, it is really about control over your own image and how you lose that control once you pass it on to someone else, online,” she said. “It is about dignity and self-empowerment,” Gul added.

Sandstorm is available online around the world in most countries, on The New Yorker’s screening room.

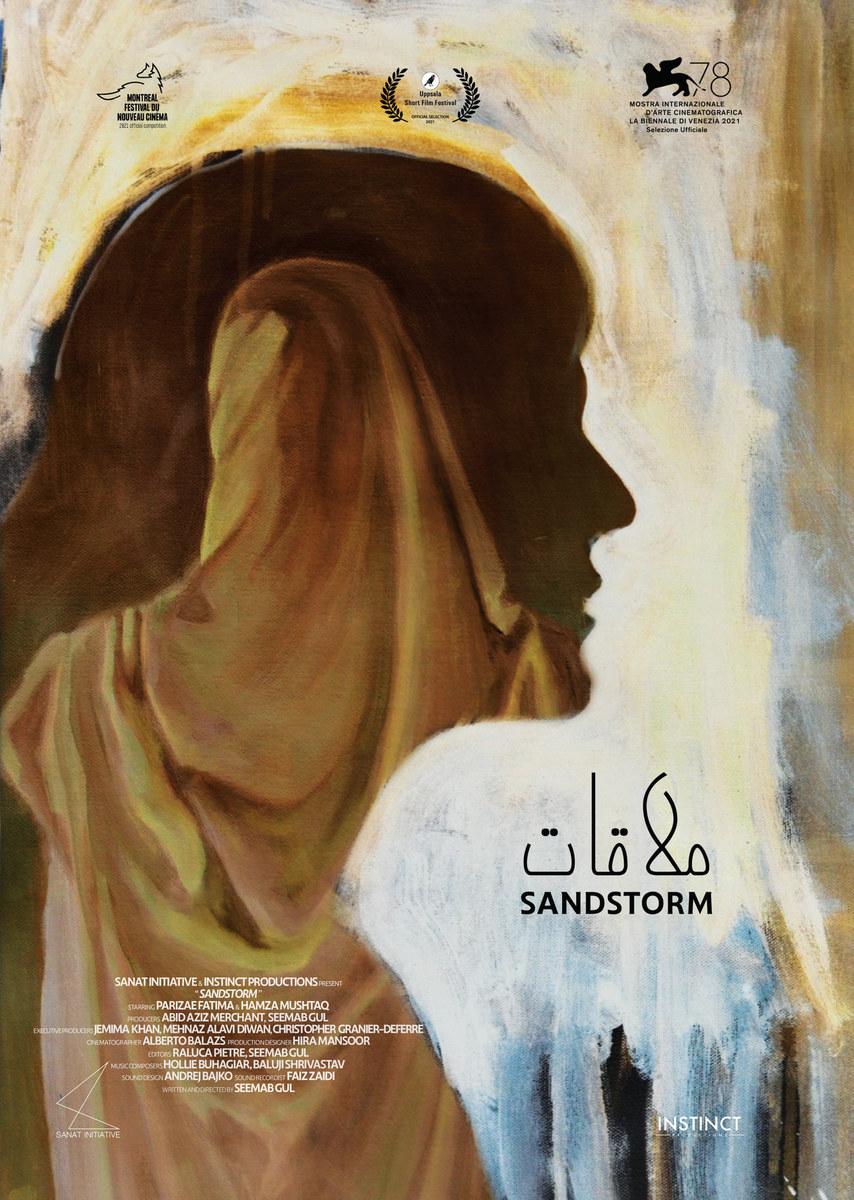

Poster of award-winning short film Sandstorm, which won big at two recent Oscar-qualifying festivals, HollyShorts Film Festival 2022 and Flickers Rhode Island International Film Festival 2022. (Supplied)

Merchant, the film’s producer, said the team wanted Sandstorm to make it big at international film festivals as Pakistan did not seem to be a viable market for short films.

“Pakistani films are not very well known internationally so getting the right visibility, especially in Europe, was the aim,” he said. “This is the market where you get funds and grants from respective governments.”

He said funding was not easily available in Pakistan, the only exception being TV channels that fund films or commercial filmmakers who receive funding from the channels and other sources.

“For independent filmmakers, that is not a possibility,” Merchant added. “So, the only way we can make films like we want to is by accessing European funds from Germany, from France, from Netherlands, so on and so forth.”