LANGLEY: They like to call it ‘the greatest museum you’ll never see.’

Tucked away in the corridors of its Langley, Virginia, headquarters, the revamped Central Intelligence Agency museum – while still closed to the public – is revealing some newly declassified artifacts from the spy agency’s most storied operations since its founding 75 years ago.

Top among them: a slightly more than foot-long (30.5 cm) scale model of the compound in Kabul, Afghanistan, that was used to brief President Joe Biden before the drone strike that killed Al-Qaeda leader Ayman Al-Zawahiri just two months ago.

A model of Al-Zawahiri compound which was used to brief U.S. President Joe Biden on the mission that killed Al Qaeda's leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, is on display at the newly revamped Central Intelligence Agency museum, which is revealing some newly declassified artifacts from the spy agency's most storied operations since it's founding 75 years ago, at CIA headquarters in McLean, Virginia, U.S., September 24, 2022. (REUTERS)

“It’s very unusual for something to get declassified that quickly,” said Janelle Neises, the museum’s deputy director.

“We use our artifacts to tell our stories. It’s a way to be really honest and transparent about the CIA, which is sometimes hard,” said Neises, who joined the museum’s director Robert Byer on Saturday in leading a media on a tour of renovated exhibits.

A replica of the tunnel that spanned West to East Berlin, jointly built by CIA and the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI-6) during the Cold War, is on display at the revamped Central Intelligence Agency museum at CIA headquarters in McLean, Virginia, U.S., September 24, 2022. (REUTERS)

The items, some of which are available to view online, are part of a broader effort to expand public outreach and recruitment by the legendary but secretive agency, known as much in some quarters for its scandals as for intelligence successes.

CIA officials often say that the agency’s successes are secret but its failures sometimes public.

The newly revamped Central Intelligence Agency museum, while still closed to the public, features a ceiling with hidden messages, at CIA headquarters in McLean, Virginia, U.S., September 24, 2022. (REUTERS)

The outreach effort includes the launch earlier this week of the CIA’s first public podcast on which Director William Burns said the agency sought to “demystify” its work at a time when “trust in institutions is in such short supply.”

The hundreds of museum items, some of which have been on display since the 1980s, are all declassified. Neises said the agency does from time to time loan some to presidential libraries and other non-profit museums.

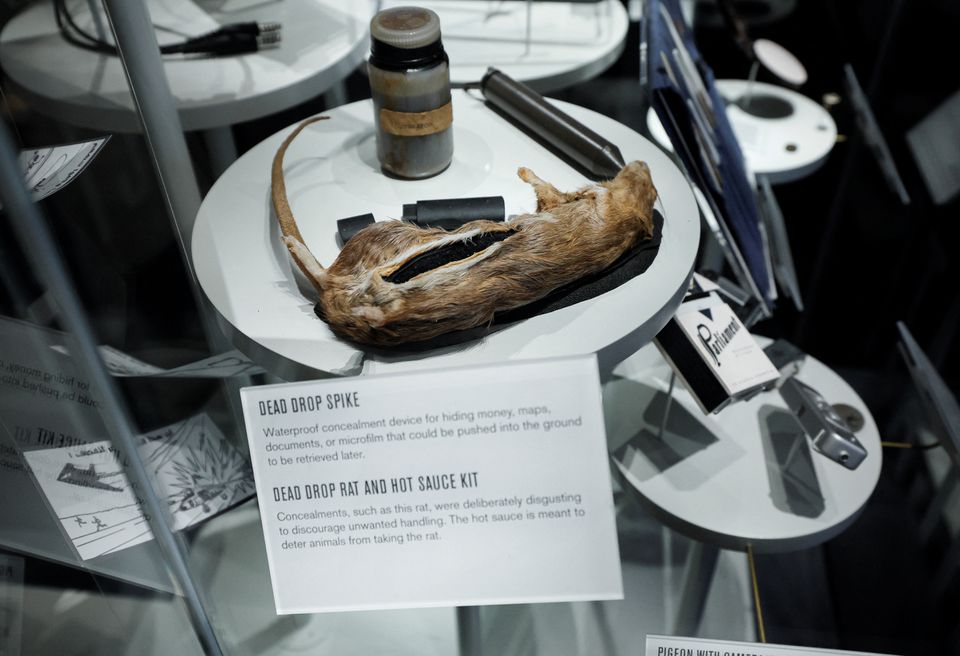

A dead drop rat and other tools used in spycraft are on display at the newly revamped Central Intelligence Agency museum, at CIA headquarters in McLean, Virginia, U.S., September 24, 2022. (REUTERS)

On view for those cleared to visit: the AKM assault rifle toted by Osama bin Laden the night US Navy SEALs killed him in a raid of his Abbottabad, Pakistan, compound in 2011, and a leather jacket found with former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein when he was captured in 2003.

Other exhibits range from flight suits worn by pilots of Cold War-era U-2 and A-12 spy planes to a wood-framed saddle, similar to those used by members of CIA’s Team Alpha as they navigated Afghanistan’s mountainous terrain by horseback shortly after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks on the United States.

Artifacts from Iraq including playing cards of the most-wanted members of Saddam Hussein's government are on display at the newly revamped Central Intelligence Agency museum, which is revealing some newly declassified artifacts from the spy agency's most storied operations since it's founding 75 years ago, at CIA headquarters in McLean, Virginia, U.S., September 24, 2022. (REUTERS)

None of the items, all of which are considered US government heritage assets, have been assessed for value.

“Our museum is operational,” Neises said. “It’s here for our workforce to learn from our successes and failures.”