LONDON: One day, in late February 1986, a young man from Jubail in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province decided to put his new 4WD through its paces on the sand dunes west of the coastal city. Before very long, however, he made two startling discoveries.

The first was that neither he nor his new car were well suited to dune-bashing, as both man and machine soon found themselves stuck fast in the sand.

But then, in the words of a paper published in the journal “Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy” in 1994, “in the process of digging out, (he) discovered he was on top of a wall which disappeared down into the sand.”

Although the young man had no idea what he had found, he realized it must have been very old. Having freed his vehicle and returned to Jubail, he alerted the authorities about his discovery.

What he had stumbled on, it would later transpire, was the remains of a Christian church, long buried beneath the drifting sands.

Archaeologists who later excavated the site would find an open, walled courtyard, about 20 meters long, with doorways leading onto three rooms.

Although Christianity began to wane as Islam rose, Christians were not seen as outsiders at that time, for the simple reason “they were family.” (Department of Archaeology and Tourism Umm al-Quwain)

Although Christianity began to wane as Islam rose, Christians were not seen as outsiders at that time, for the simple reason “they were family.” (Department of Archaeology and Tourism Umm al-Quwain)

The central room, at the eastern end of the structure, was determined to be the sanctuary, where the altar would have stood. The room to the north was where the bread and wine for the Christian ritual of the Eucharist would have been assembled. To the south was the sacristy, where the sacred vessels and the priest’s robes were kept.

All the walls were covered in gypsum plaster, in which there were clear impressions of four crosses, the distinctive symbol of Christianity, each about 30 cm tall.

Several stone columns remained intact, as did a pair of decorative plaster friezes, featuring a pattern of flowers linked by vine motifs.

This, it turned out, was not just any church. Dated by archaeologists to the 4th century AD, it predated the coming of Islam by about 300 years, and proved to be among the oldest known Christian churches in the world.

The discovery was just one small piece in a historical jigsaw puzzle which has since been all but completed, assembling a picture of a time when two faiths, Islam and Christianity, coexisted along the shores of the Arabian Gulf.

Now, 36 years after that young Saudi’s discovery, another major piece has been added to the puzzle with the excavation of a Christian monastery on Siniyah Island, just off the coast of Umm Al-Quwain in the UAE.

Using pottery and carbon dating of organic remains found in the foundations of the complex, the monastery has been dated to between 534 and 656 AD, a period that spans the lifetime of Prophet Muhammad, who was born around the year 570 and died in 632.

The site appears to have been abandoned during the 8th century — not as a result of a clash between the two faiths, but because of an internal conflict within Islam, archaeologists believe.

“Eventually the walls collapsed, and the windblown sands moved over them, leaving low mounds with building debris, and pottery, glass and coins, which were visible on the surface,” said Tim Power, associate professor of archaeology at the UAE University in Al-Ain and co-director of the Siniyah Island Archaeology Project.

The site where the Christian altar once stood against the rear wall of the Siniyah Island building’s sanctuary. (Siniyah Island Archaelogy Project)

“But there is absolutely no evidence of destruction, or of deliberate damage to the site. We even have the stem of the glass chalice that was being used to deliver the Eucharist, in its original place, and the bowl that was used for mixing the Eucharist wine, also in situ.

“It really does feel like they just got up one day and walked away.”

Power believes the site was abandoned not because of religious differences, “but because of the Abbasid invasion of 750 AD, which fits with our ceramic dating and radio-carbon dating for the abandonment.”

In 750 AD, the Abbasid caliphate, based in Mesopotamia, overthrew the Umayyads. “We know from the Arabic historical sources that the Abbasid invasion was very violent, and the coastal towns of the emirates were destroyed,” he said.

“So I think these people fled in terror at the prospect of the invasion by the imperial authorities in Iraq, which were trying to maintain control of their restive provinces. It was a conflict between two different groups of Muslims.”

The existence of the monastery right up until this moment in the mid-8th century, more than a hundred years after the death of Prophet Muhammad, is evidence that “there was clearly a degree of intercommunal, interfaith tolerance at the local level.”

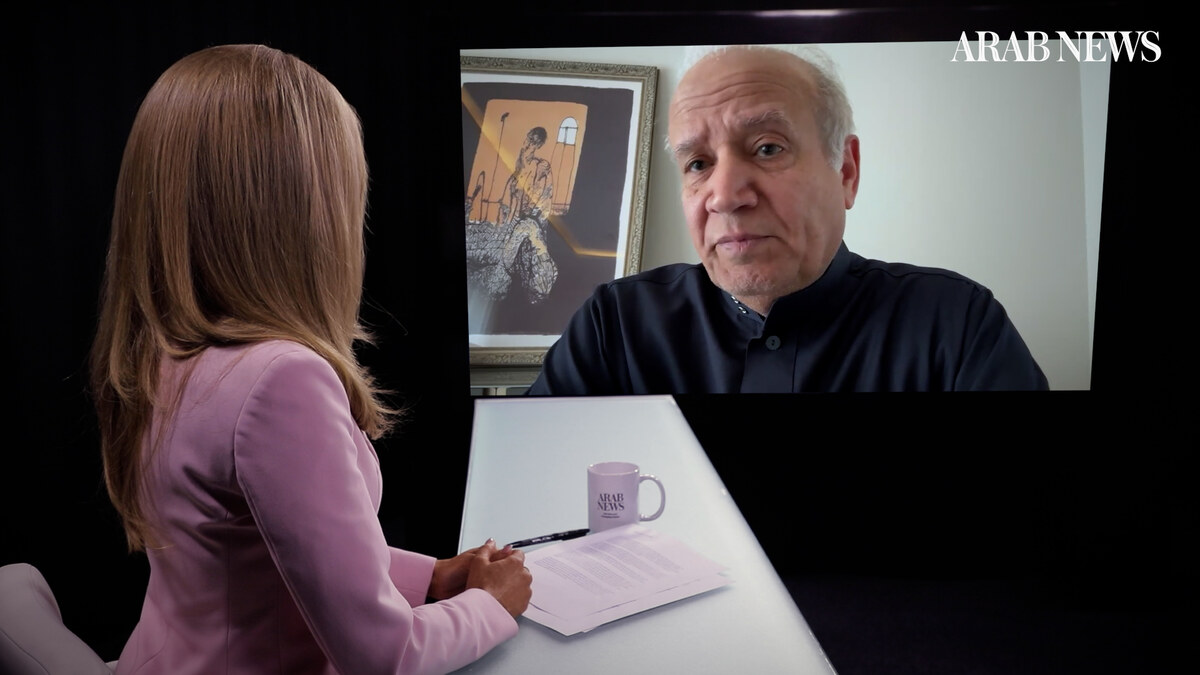

Power says it is a common mistake to assume that the Christians of the Gulf at the time of the rise of Islam were outsiders.

“It is worth remembering that Christianity is a Middle Eastern religion. Jesus Christ spoke Aramaic, which was the language of the Middle East at the time of the Arab conquests. These churches and monasteries were most likely not built by foreigners visiting these shores, but built by and for the local Christian Arab community.

“There is a great deal of historical and inscriptional evidence which tells us that probably the majority of the Arabian Peninsula until the rise of Islam was Christianized.”

Power says it is a common mistake to assume that the Christians of the Gulf at the time of the rise of Islam were outsiders. (Department of Archaeology and Tourism Umm al-Quwain)

And although Christianity began to wane as Islam rose, Christians were not seen as outsiders at that time, for the simple reason “they were family.”

“Over the course of several generations Christian Arabs started to convert to Islam. But as a Muslim you might have a cousin, say, who’s a Christian and, as they are still today, these were very strongly kinship communities.

“Membership of a tribe was probably the crucial piece of your identity, and religious affiliation almost secondary.”

This is the second discovery of a Christian monastery in the UAE. In 1992, the newly formed Abu Dhabi Islands Archaeological Survey, founded by the UAE’s then-president, Sheikh Zayed, began investigations on three islands.

On one of them, Sir Bani Yas, just 7 km off the coast in the Western Region of Abu Dhabi, they quickly found some tantalizing clues — the remains of several courtyard houses and fragments of pottery dated to between the 6th and 7th centuries AD.

The first evidence of Christian occupation was unearthed in 1994 — fragments of plaster crosses that bore a striking resemblance to others that had been found previously at several locations in the Gulf.

Over the next two seasons, as the survey reported in a paper published in 1997, “a very large, complex structure emerged ... which now proves to be a monastery, with a church standing in its center within a courtyard.”

There is now a wealth of evidence, both textual and archaeological, testifying to the existence of Christianity in the Gulf from at least the 4th century AD until the first couple of centuries of Islam.

According to sources written in Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic spoken by Christian communities in the Middle East from about the 1st to the 8th century AD, the Church of the East, which was also known as the Nestorian Church, thrived in a region known as Beth Qatraye.

A frieze from a Christian monastery on Sir Bani Yas. (DCT Abu Dhabi)

According to the Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage, published by the Syriac Institute, which exists to promote the study and preservation of the Syriac heritage and language, Beth Qatraye, “land of the Qataris,” included “not only the peninsula of Qaṭar, but also its hinterland Yamama” — today a historic region within Saudi Arabia — “and the entire coast of northeast Arabia as far as the peninsula of Musandam, in present-day Oman, along with the islands” of the Gulf.

References to Beth Qaṭraye are found in a number of Christian documents written in the years leading up to the emergence of Islam. The earliest comes from the “Chronicle of Arbela,” written in Syriac and supposedly composed between 551 and 569 AD by a monk from what is now Irbil, in the Kurdistan region of Iraq.

The chronicle refers to the existence of several Christian dioceses in the Gulf, and specifically in the area of Beth Qatraye, dating back as far as 225 AD.

First “rediscovered” in 1907, the chronicle has fallen in and out of favor with ecclesiastical historians. But although its authenticity has been challenged, many of its details appear to have been confirmed by subsequent archaeological discoveries in the Gulf.

There is, however, no doubt among scholars about the authenticity of preserved church correspondence that shows Christianity was established in Beth Qaṭraye by at least the 4th century.

Ishoyahb III, Patriarch of the Church of the East from 649 to 659, left a wealth of letters for historians to pore over, including five sent from his base in Adiabene in northern Mesopotamia to the clergy and faithful of Beth Qatraye.

Another valued source that mentions the region of Beth Qatraye is the “Book of Governors,” a monastic history written in the mid-9th century by Thomas, a bishop of Marga, an east Syriac diocese in the metropolitan province of Adiabene, a province of the Sasanian Empire in Mesopotamia.

Archaeologists who later excavated the site would find an open, walled courtyard, about 20 meters long, with doorways leading onto three rooms. (Supplied)

There is also an abundance of archaeological evidence of a Christian presence in the Gulf. The first clues were found in 1931 at Hira, an ancient city in south-central Iraq, which in about the 3rd century AD became the capital of the Lakhmids, a Christian tribe originally from Yemen.

In 1960, the French archaeologist Roman Ghirshman excavated a 7th-century Christian monastery on Iran’s Kharg Island, and in 1988 a church was discovered at Al-Qusur on Failaka Island, Kuwait.

Shortly before the church at Jubayl was discovered, three Christian crosses were found nearby at Jabal Berri, a rock outcrop about 10 km southwest of the city, some 7 km inland from the coast. Two were made of bronze, and the third, just 5 cm tall, was carved from a single piece of mother of pearl.

Ecclesiastical and Arabic records not only point to considerable Christian activity in areas that are now part of Saudi Arabia, but also demonstrate that “far from undergoing a decline, Christianity flourished in the Gulf immediately after the Muslim conquest,” as Robert Carter, professor of Arabian and Middle Eastern archaeology at UCL Qatar, wrote in the 2013 book, “Les preludes de l’Islam.”

Indeed, there was “a burst of Christian activity from the late 7th and/or 8th century, extending into the early 9th century at Kharg.”

One of the sites where Christianity flourished was on the island of Tarut, just off the modern-day governorate of Qatif in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. It was here in 635 AD that Muslim forces put an end to the “ridda,” the apostasy movement in the eastern region, in a final battle that was fought at Darin on the island.

However, “the Muslim conquest did not put an end to the Nestorian community here,” as Daniel Potts, professor of ancient Near Eastern archaeology and history at New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, wrote in a paper published in the journal “Expedition” in 1984.

There are records of a major synod, or church council, having taken place on the island more than 40 years later, in 676.

This was a significant gathering, as it was at this synod that the Christian practice of marriage in a church was first established, when George I, the chief bishop of the Church of the East, issued a ruling that henceforth only those unions blessed by a priest would be regarded as legitimate.

“There is absolutely no evidence of destruction or of deliberate damage to the Siniyah Island site,” Tim Power, associate professor of archaeology, UAE University, Al-Ain. (Supplied)

In mid-November this year, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman announced that up to SR2.64 billion ($703 million) had been allocated for the development of the island of Tarut, which today is home to 120,000 people, to preserve its heritage and enhance its potential as a tourism destination.

Tarut was not the only Christian site in what is now Saudi Arabia. Other centers or churches mentioned in Syrian texts included “Hagar” and “Juwatha,” both believed to have been located somewhere in Al-Hasa oasis, and at nearby Al-Qatif and Abu Ali Island, just north of Jubail.

Eventually, all these Christians sites, from Jubail in Saudi Arabia to Umm Al-Quwain in the UAE, disappeared from history. According to John Langfeldt, an American priest and historian who wrote the first paper about the church in Jubail after visiting the site in 1993, they did so as part of a peaceful process of assimilation.

“There was no forced conversion of the populace to Islam (and) Christianity remained the primary religious allegiance of the vast majority of the population,” Langfeldt wrote in a paper published in the journal “Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy in 1994.”

“Gradually, over several centuries, probably due to several factors — such as the burden of ... tax, isolation from outside Christian contact, convenience, some fine qualities of Islam, and the excellent witness of its adherents — almost all of the population was Islamized.”