LONDON: Hit by endless delays, political upheavals and, most recently, the curse of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Grand Egyptian Museum has been a long time coming.

But 2023 is the year that the modern complex billed as the world’s largest museum devoted to a single civilization is finally due to open, just in time to help Egypt to revive its badly missed tourism industry.

The opening of the building will be more than an opportunity to kickstart the country’s battered economy. It represents a symbolic cultural victory, not only for Egypt but also an entire region whose ancient history was looted by generations of Western adventurers.

No one knows how the young pharaoh Tutankhamun met his death at the age of 18, around 3,344 years ago. Theories — none of them proven — include malaria, a chariot accident, a bone disorder and even murder.

One thing we do know, however, is that when the “boy king” approached his untimely end, he would have done so comforted by the belief that he and the many possessions that would be buried with his mummified body would soon be on their way to the afterworld, and a glorious afterlife spent in the company of the god Osiris.

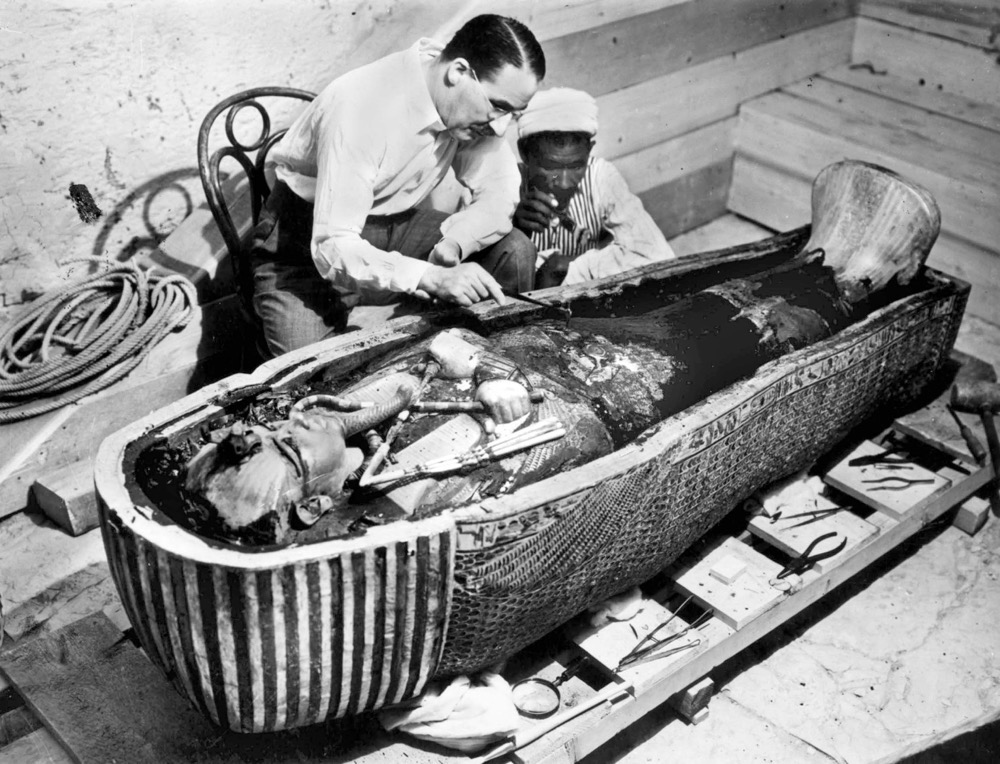

But that eternal journey was rudely interrupted in 1922 when the British archaeologist and part-time antiquities dealer Howard Carter discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb.

The only place to see all 5,400 of the artifacts in the Tutankhamun collection from now on will be at the Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo. (AFP)

Like all Western archaeologist-adventurers of his time, Carter’s plan was to ship the bulk of the treasures back to Europe and sell them to museums.

That this plan was par for the course during the heyday of heritage looting posing as scientific research is attested to by the countless thousands of artifacts, statues, funerary goods, coffins, sarcophagi and mummies from ancient Egypt that today can be found scattered about the Western world, in museums large and small.

In Carter’s case, however, such was the significance of the find that, even though Egypt was a British protectorate at the time, Egyptian officials managed to foil his plans — more or less. In recent years it has emerged that Carter and his colleagues managed to smuggle various items out of Egypt, which they sold to a number of museums in the West.

In 2010 Egypt welcomed the return by the Metropolitan Museum in New York of 19 items taken from Tutankhamun’s tomb. “These objects,” said Thomas P. Campbell, director of the Met at the time, “were never meant to have left Egypt, and therefore should rightfully belong to the Government of Egypt.”

Regardless, since the 1960s, it seems as though the Tutankhamun collection has spent more time out of Egypt than in, circling the world in a series of endless tours.

The first touring exhibition, “Tutankhamun Treasure,” was seen in 24 cities in the US and Canada between 1961 and 1966. Between 1961 and 2021, much of the treasure spent 30 years outside Egypt — three decades during which generations of young Egyptians were denied access to some of the most totemic elements of their heritage.

The existence of the long-awaited Grand Egyptian Museum will bring this disgraceful state of affairs to an end.

All 5,400 of the artifacts entombed with the king more than 3,300 years ago, including the iconic golden mask, have finally been reunited for the first time since they were unearthed by Carter in the Valley of the Kings.

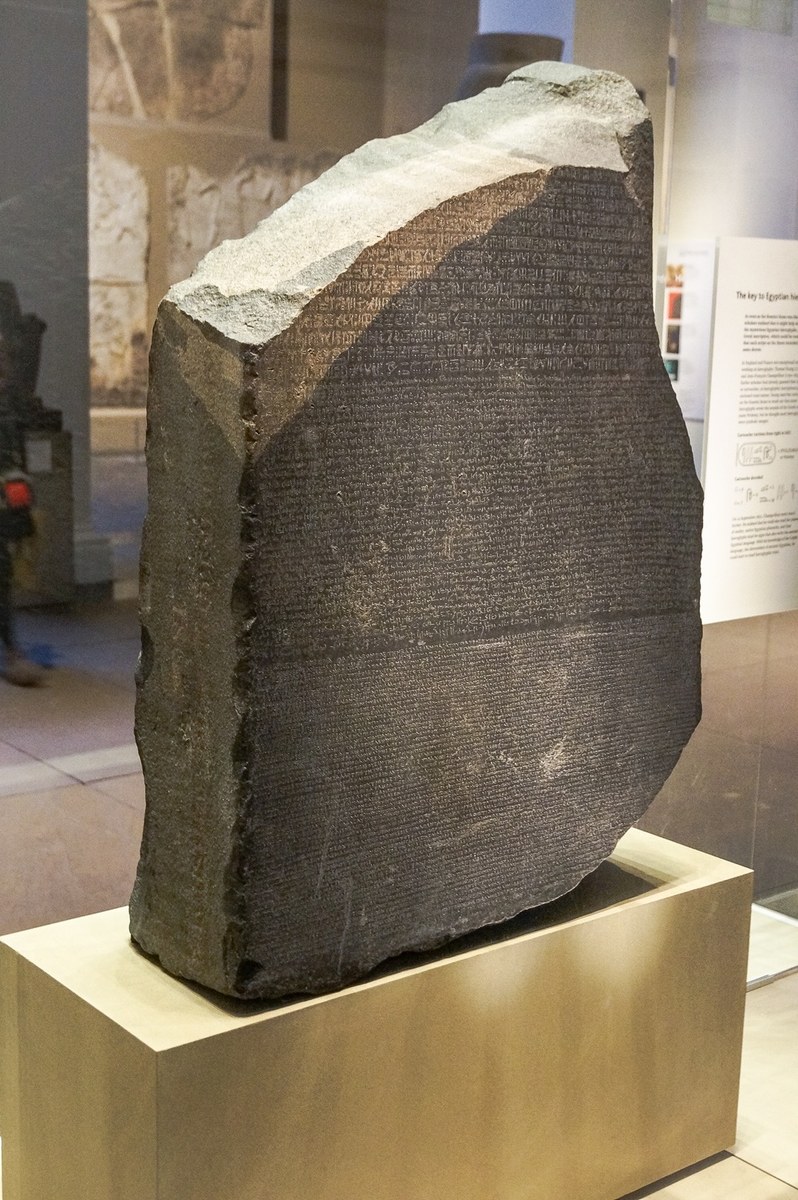

Rosetta Stone at the British Museum.

From now on, the only place to see them will be in the correct place — in Egypt, at the Grand Egyptian Museum.

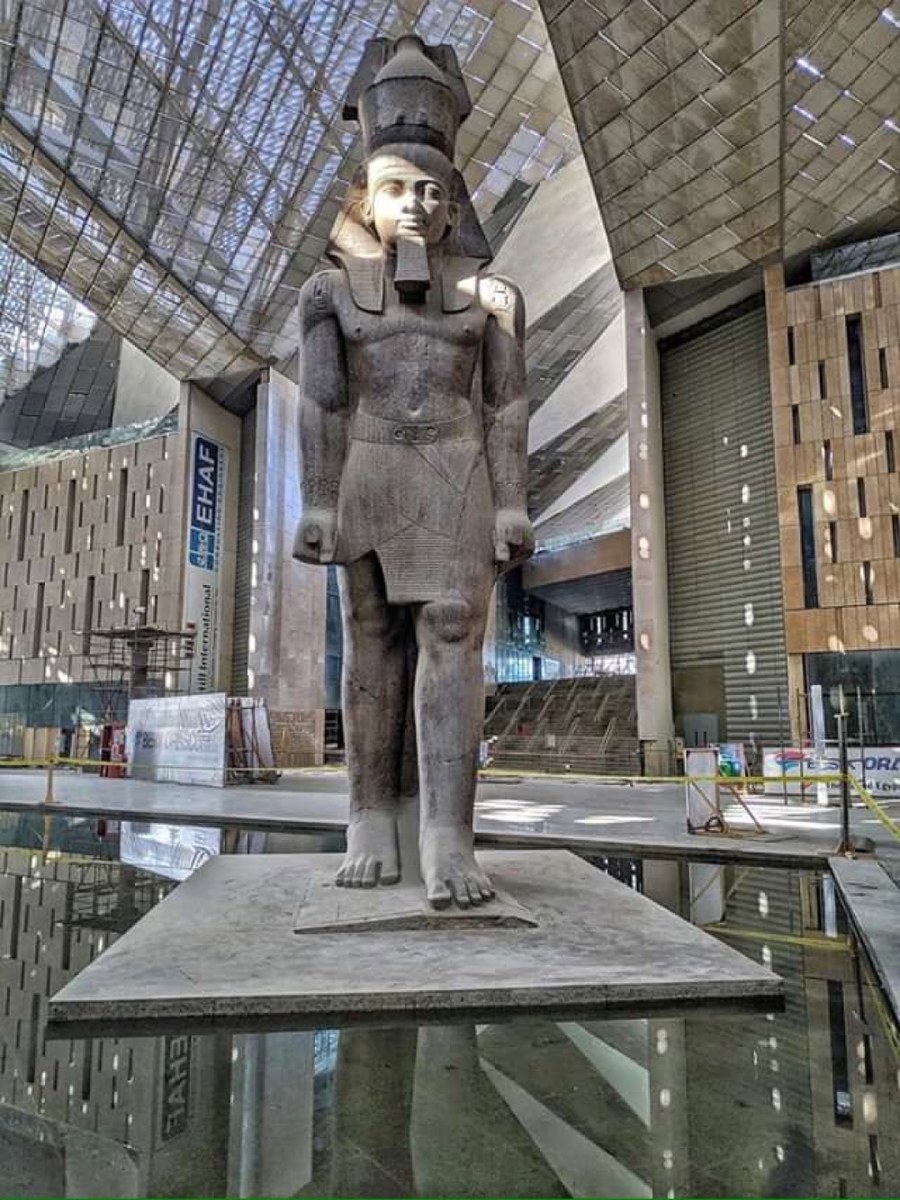

This is a museum like no other. Covering a site of almost 500,000 square meters, the building offers visitors a spectacular panoramic view of the nearby pyramids of Giza.

Besides the headliner, Tutankhamun, the museum houses more than 100,000 artifacts from Egypt’s rich past, dating from prehistory through pharaonic times to the Greek and Roman periods. An 11-meter statue of Ramses the Great dominates the museum’s vast, light-filled entrance atrium, which was built around the imposing 83-ton granite figure.

In the West, museum curators mutter about the superior abilities of Western institutions to protect the heritage of other countries, which, by inference, they deem incapable of doing so.

Egypt, however, has undisputed, and indeed unrivaled, expertise when it comes to protecting and conserving artifacts from its past. A conservation center at the museum has been operational since 2010, having made its mark with Tutankhamun’s outer wooden coffin, which has undergone eight months of careful preservation.

The British Museum argues it is “a museum for the world” — a place where the entire history of the evolution of global civilization can be seen by the whole world, all in one place.

That is fine, provided one lives in London, or has the means and inclination to travel there. But for most Egyptians, that is not an option.

English egyptologist Howard Carter (1873-1939) working on the golden sarcophagus of Tutankhamun in Egypt in 1922. (Apic/Getty Images)

In 2003, the last time Egypt made a determined but ultimately futile attempt to persuade Britain to part with the Rosetta Stone, one of the icons of Egyptian heritage, the British Daily Telegraph remarked sniffily that “if the stone were to be moved” — at that stage, to the Cairo Museum — “it would be seen by far fewer people than is the case today, about 2.5 million visitors a year, compared with the 5.5 million who visit the British Museum annually.”

Again: How many of those 5.5 million are Egyptians, and how many more people from around the world might travel to Egypt to see the stone if it were in the Grand Egyptian Museum?

The opening of the museum comes a century since the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, and 200 years since the deciphering of the Rosetta Stone, the ancient stele that held the key to the translation of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

In the past, Egypt has made repeated attempts to have the Rosetta Stone returned. Looted by Napoleon’s troops during his Egyptian campaign of 1798 to 1801, it was seized from him in turn by the British and shipped to the UK in 1802, where it was presented to the British Museum by King George III.

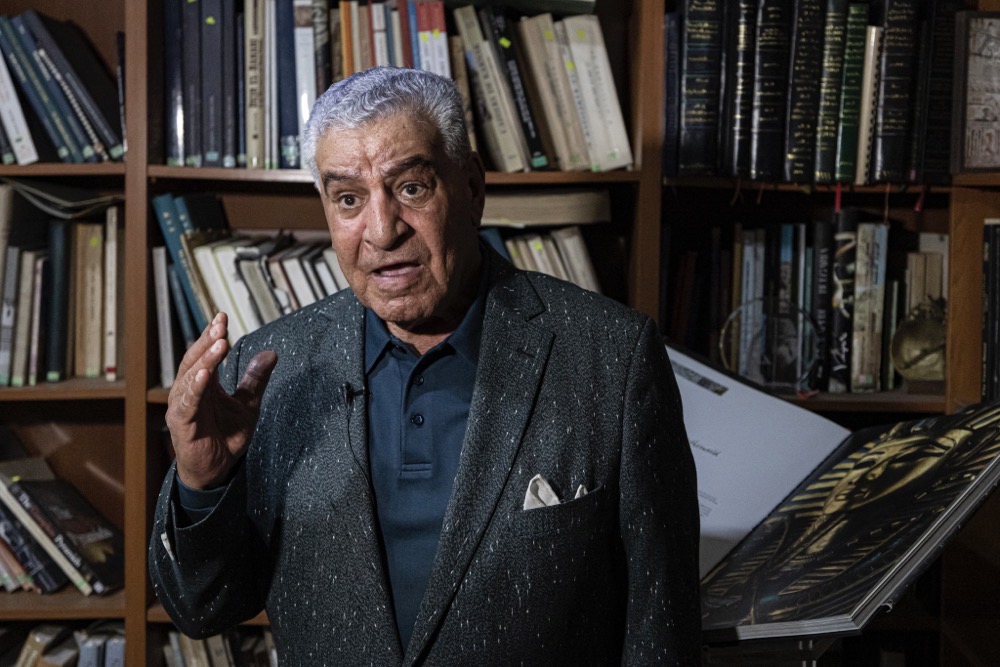

In 2003, Egyptologist Dr. Zahi Hawass, then director of the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Cairo and a future minister of antiquities, told the British press that “if the British want to be remembered, if they want to restore their reputation, they should volunteer to return the Rosetta Stone because it is the icon of our Egyptian identity.”

In 2020, Hawass renewed his campaign, broadening Egypt’s claims to include the return of the bust of Nefertiti from the Egyptian Museum of Berlin, and the Zodiac of Dendera and several other pieces from the Louvre in Paris.

The pressure on international institutions to do the right thing increased in December, when Germany returned to Nigeria 21 artifacts that were among thousands looted by British troops from the west African kingdom of Benin 125 years ago. More than 100 of the so-called Benin bronzes are also held by the University of Cambridge, which last month also agreed to return them to their homeland.

Egypt’s former antiquities minister Zahi Hawass, who campaigned for the return of Egyptian artifacts. (AFP)

However, the bulk of the Benin artifacts are in the possession of the British Museum, which says it has “excellent long-term working relationships with Nigerian colleagues and institutions,” but nevertheless has so far refused to return the items.

The museum also shows no sign of willingness to part with its Egyptian artifacts. In addition to 38 items “found or acquired” by Howard Carter of Tutankhamun fame, it holds more than 45,000 other artifacts from ancient Egypt — of which fewer than 2,000 are on display.

In February 2020, Dr. Khaled El-Anany, minister of tourism and antiquities, said Egypt was “in direct negotiations with the British Museum and other museums,” insisting that “any objects which left Egypt in an illegal way will return to Egypt.”

As ever, the museum plays its “museum of the world” card.

“At the British Museum, visitors can see the Rosetta Stone alongside other pharaonic temple monuments, but also within the broader context of other ancient cultures, allowing a global public to examine cultural identities and explore the complex network of interconnected human history,” a spokesperson for the British Museum told Arab News.

An 11-meter statue of Ramses the Great at the Grand Egyptian Museum. (Supplied)

The British Museum also points out that it is one of four European museums collaborating with Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities to renovate the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square as part of a €3.1 million EU-funded project. But does this really compensate for centuries of looting?

Whether any of the world’s museums harboring artifacts taken from Egypt during the imperialist era will take this golden opportunity to return them, boosting their reputations in the process, remains to be seen.

But if ever there was a good time for Egypt’s heritage to be restored to its rightful home, it is surely now, so it may be displayed in the country’s vast new temple to its past, for the benefit of all Egyptians and the many tourists from all over the world who will surely journey to see it.

Twitter: @JonathanGornall