IRBIL, Iraqi Kurdistan: Fewer Syrians were killed in 2022 than in any other year since the civil war began in 2011. What is unclear is whether this represents the beginning of the end of this seemingly endless conflict or merely an interlude before another round of grinding violence.

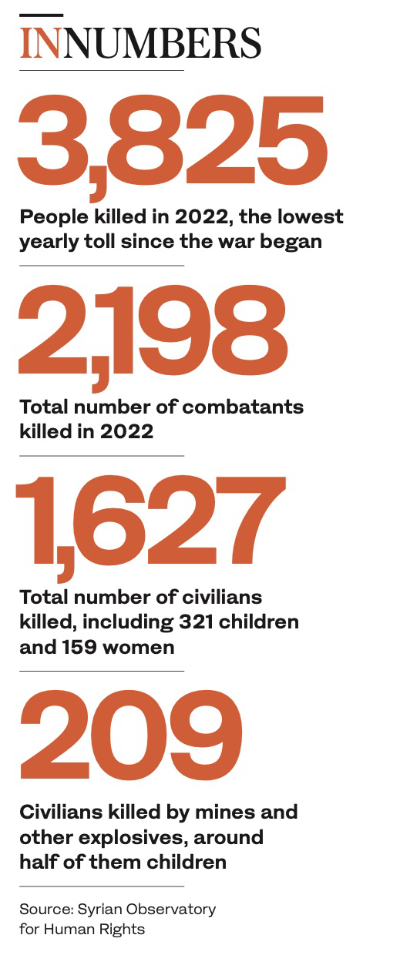

An estimated 3,825 Syrians perished in 2022 — a small decrease from the 3,882 who lost their lives in 2021, but still a continuation of the observable downward trend in the overall deaths caused by the war since 2018.

There is no guarantee, however, that this trend will continue into 2023. While violence overall has subsided in recent years, there are still isolated flashpoints across the country that could yet explode depending on local political factors.

There is no guarantee, however, that this trend will continue into 2023. While violence overall has subsided in recent years, there are still isolated flashpoints across the country that could yet explode depending on local political factors.

Aron Lund, a fellow at Century International and a Middle East analyst at the Swedish Defense Research Agency, has observed two main trends play out in Syria over the past few years.

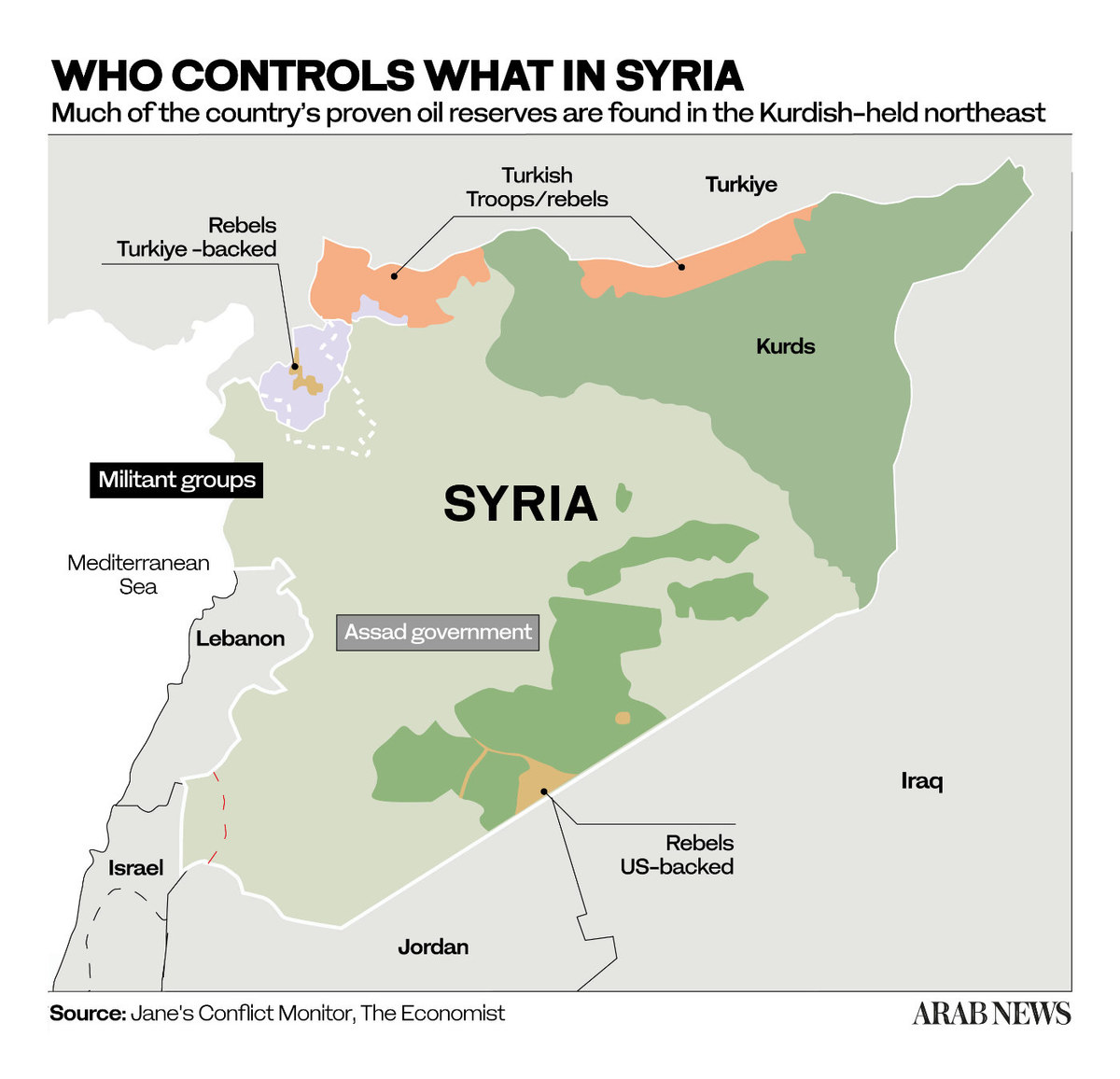

“One is toward stagnation and more thoroughly frozen frontlines. It’s the result of all-around exhaustion and the presence of Russian, Turkish and US troops that seek to deconflict their spheres of influence,” he told Arab News.

“The other trend has been one of intensified humanitarian despair. It is a result of the country’s economic decline, which began to accelerate dramatically around 2019-2020.

A mourner sits at a cemetery during the burial of a fighter of the Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG), in Syria's Kurdish-majority city of Qamishli, on Dec. 7, 2022. (AFP file photo)

“There are crippling shortages of key imports, energy and water. New UN data says 15.3 million Syrians now depend on humanitarian assistance, or nearly 70 percent of the country’s current population.

“So even though violence has ebbed to its lowest point, the situation for civilians is, paradoxically, worse than at any previous time.”

Although Syria has experienced a period of relative stability, Lund notes that it has been “inherently fragile.”

“The status quo could break down due to unpredictable internal developments, with social conditions and governance being dragged down by the failing economy,” he said.

“Conflict actors may lose control or grow desperate. New crises can also be set in motion by external factors.”

External factors could potentially include Russia and Iran being forced to reduce their military presence in the country or a shift in Turkish foreign policy. US Middle East policy could also undergo “dramatic changes” depending on the results of the next presidential election.

A Syrian fighter fires a sniper rifle during military drills by the Turkish-backed "Suleiman Shah Division" in the opposition-held Afrin region of northern Syria on Nov. 22, 2022. (AFP)

Joshua Landis, a noted Syria expert and director of both the Center of Middle East Studies and the Farzaneh Family Center for Iranian and Persian Gulf Studies at the University of Oklahoma, describes Syria’s economic prospects as “grim.”

“The proposed budget for 2023 is about $3.2 billion, compared with about $4 billion in the budget last year,” he told Arab News. “The collapsing Syrian currency means that, in dollar terms, it will be even lower.

“The deteriorating economic numbers, the fuel crisis, which has caused constant demonstrations and protest, as well as rocketing commodity prices for both wheat and fuel due to the war in Ukraine, all indicate further economic stagnation and deterioration of services for the average Syrian.”

A woman and a girl dry their clothes at a camp for those displaced by conflict in the countryside near Syria's northern city of Raqqa on Dec. 19, 2022. (AFP file)

The fall in the value of the budget and the continuing collapse of Syria’s currency strongly indicate that 2023 will be a harsher year for Syrians than 2022.

At the same time, Russia and Iran, the Bashar Assad regime’s two main sponsors, face their own mounting economic problems and may well choose to reduce their crucial financial backing.

Nicholas Heras, director of the Strategy and Innovation Unit at the New Lines Institute, believes the Syrian conflict is heading for a “decisive diplomatic moment” in 2023, with Turkiye now closer than ever to normalizing relations with Assad.

Turkish troops are pictured in the area of Kafr Jannah on the outskirts of the Syrian town of Afrin on October 18, 2022. (AFP file)

“It cannot be overstated: If Ankara reaches a deal with Damascus through Russian-backed talks, the Syrian revolution will be over,” he told Arab News.

At the same time, Turkiye has repeatedly threatened a new cross-border offensive against the US-allied and Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in northern Syria. Ankara appears to have set its sights on Tal Rifaat, a Kurdish-controlled enclave north of Aleppo.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has also hinted at plans to capture the strategically important towns of Manbij and Kobani further east.

A Syrian fighter fires an RPG during military drills by the Turkish-backed "Suleiman Shah Division" in the opposition-held Afrin region of northern Syria on November 22, 2022. (AFP)

“This Turkish saber-rattling has been going on in parallel with the resumption of public dialogue between Damascus and Ankara, so it’s a complicated issue,” Lund said.

If the rapprochement between Syria and Turkiye continues, Lund believes “some form of coordinated action is going to be very likely during the year.”

Such coordinated action could see Turkiye supporting a Russian-backed Syrian government offensive to recapture these areas or Damascus green-lighting a Turkish operation.

“Under this kind of threat, the SDF could decide to voluntarily withdraw from some areas in the hopes of securing their control elsewhere,” Lund said. “But that kind of military ballet is going to take a lot of careful coordination, and these are all stubborn, aggressive actors that tend not to take instructions very well.

“It’s not obvious what will happen. If relations break down, a military flare-up is entirely possible.”

On the other hand, Heras and Landis doubt Turkiye will mount an offensive against the SDF as long as US troops remain in northeast Syria and Joe Biden remains president. The SDF remains Washington’s main ally in the fight against Daesh in Syria.

“Biden has promised not to withdraw US troops from Syria,” Landis said. “The ongoing war between Turkiye and the SDF will mean more deaths in northeast Syria.”

US forces patrol in the town of Tel Maaruf in Syria's northeastern Hasakeh province on December 15, 2022. (AFP file)

Heras also argues that no actor can overwhelm the SDF as long as the US maintains a military presence in Syria.

“Turkiye does not have the unilateral ability to deliver large parts of northeast Syria that are under SDF control back to Assad because the US remains there,” he said.

“Turkiye wants to remove the Kurds from Syria to free up its southern border, and Assad views the SDF as an enemy, but neither country can challenge the US. And Russia cannot do the job for them.”

A deal by Syria and Turkey backed by Russia could spell an end to the Syrian revolution , say analysts. (AFP file)

As for diplomatic developments, Landis views the nascent Turkiye-Syria talks as a “ray of hope” for greater long-term stability.

“Talks with Turkiye are extremely important to ending the war,” he told Arab News. “Although significant headway can be made toward resolving many of the outstanding differences between Turkiye and Syria, the war will not end this year.”

Turkiye and Syria have many differences to hammer out before they can normalize relations. Over 4 million Syrians live within enclaves in the country’s northwest protected by Turkiye, including many Islamist fighters. Neither Assad nor these fighters welcome any form of reconciliation.

An aerial view taken on November 5, 2020, shows a refugee camp in the Syrian town of Salwah, less than 10 kilometres from the Syria-Turkey border. (AFP file)

“Although Turkiye has said it is willing to withdraw from these areas, it has many preconditions, some — such as political compromise with the opposition — the Assad regime is unlikely to accept,” Landis said.

US and European sanctions against Russia and Iran will likely impact Syria over the coming year. Landis notes the 2015 Iran nuclear deal is effectively dead, and the new US budget will impose new sanctions on Syria.

“This all means that Syrians face another year of belt tightening, deterioration in services, electricity shortages and health problems,” Landis said.

“Much will depend on whether the winter rains bring relief to the persistent drought and whether headway is made in negotiating peace with Turkiye.”