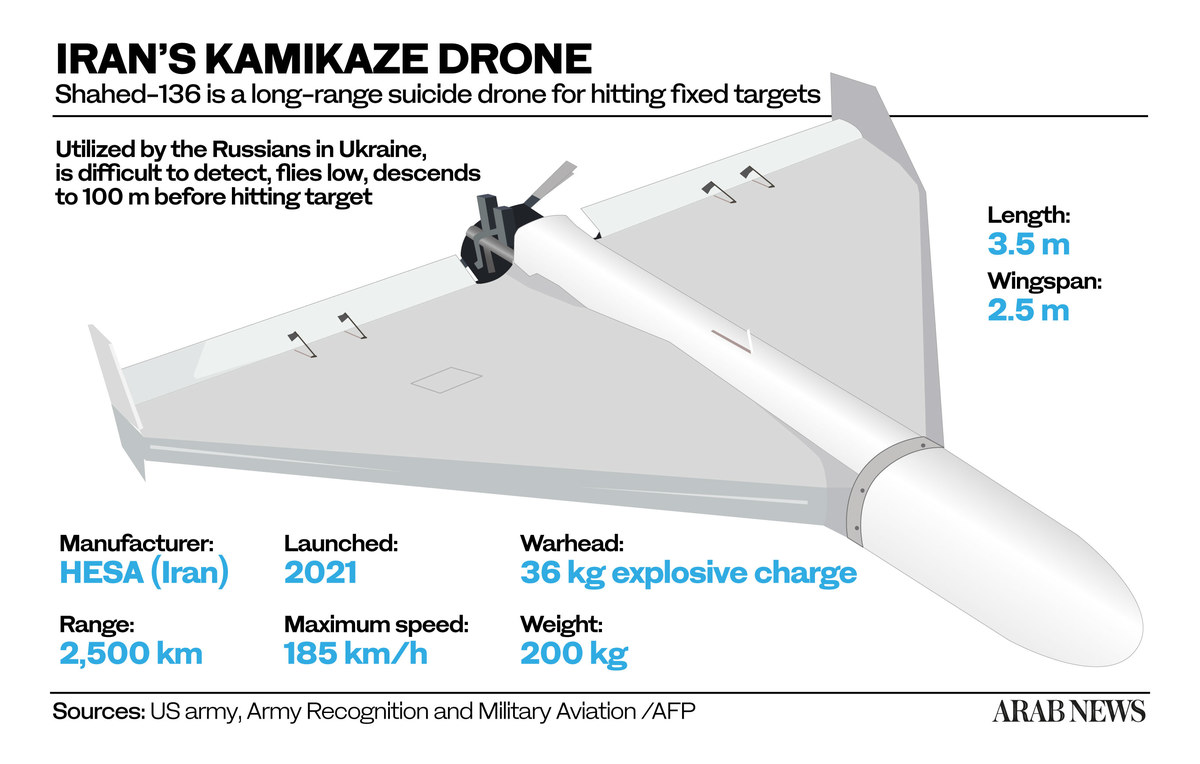

WASHINGTON, D.C.: The distinctive sound of an approaching wave of loitering munitions, commonly known as kamikaze drones, has become all too familiar over the cities of Ukraine since Iran began supplying the Russian military with its domestically designed and manufactured Shahed-136.

With its roughly 2,000 km range and 30 kg explosive payload, these destructive, swarming drones have become an almost daily terror for civilians in the capital Kyiv since September, routinely striking apartment buildings and energy infrastructure.

“The Russian purchase and deployment of Iranian drones has allowed Russia to attack the broad range of civilian infrastructure in Ukraine,” David DesRoches, a military expert at the US National Defense University, told Arab News.

Designed and built by an Iranian defense manufacturer closely linked to the regime’s powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the Shahed is low-tech compared with the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) systems developed by other nations.

However, their strategic utility lies in the fact that they can be mass produced at a relatively low cost. According to Ukrainian officials, the Russian military has ordered more than 2,000 of these drones and has been in talks to establish a joint manufacturing facility on Russian soil.

A recent report by the Washington Institute also claims the Kremlin has expressed interest in purchasing more advanced Iranian drones, such as the Arash, which has a longer range and can carry a larger explosive payload than the Shahed.

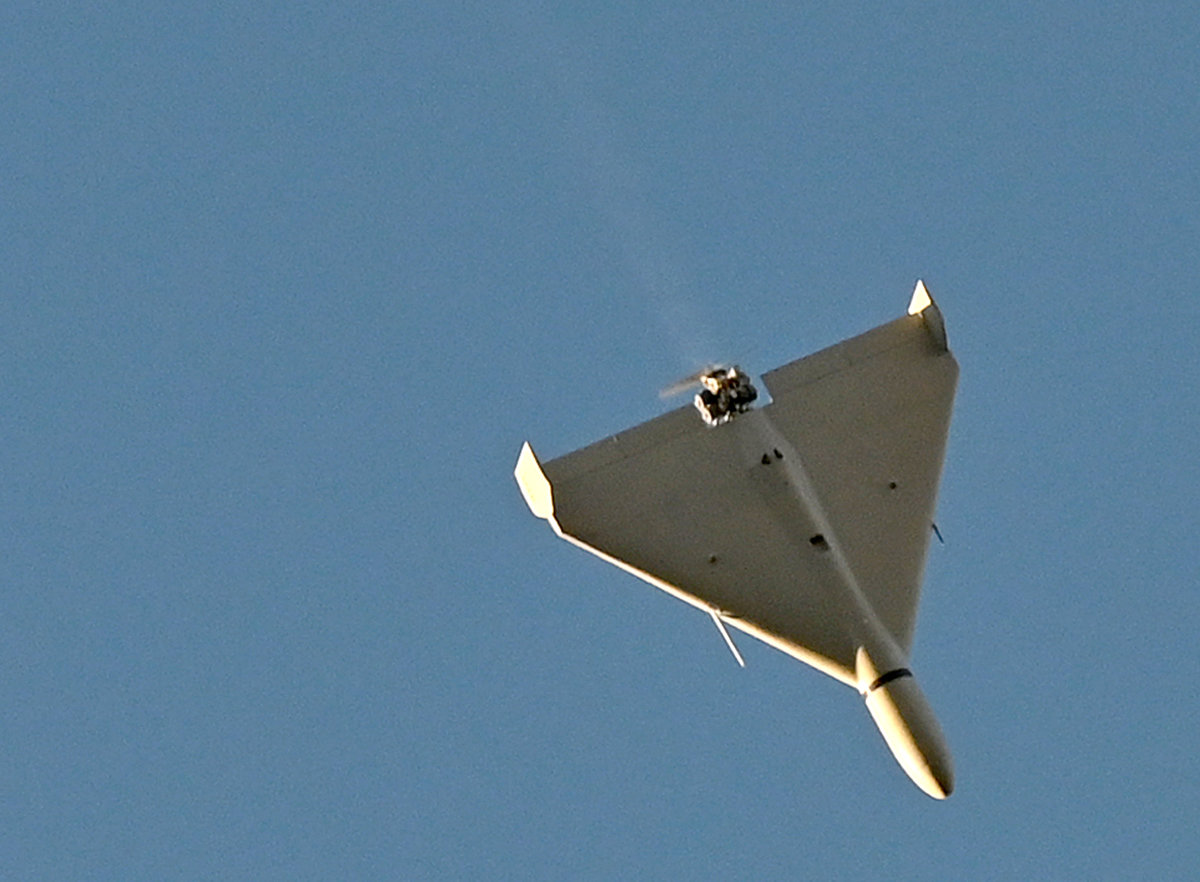

A drone flies over Kyiv during an attack on October 17, 2022, amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine. (AFP file)

But before Iran’s drones made their debut in the largest and most significant conflict on the European continent since the Second World War, they were battle-tested across multiple fronts in the Middle East where the IRGC and its proxies are active.

Iran has been able to trial its drone technology against US-built air defenses stationed in Iraq and the Arabian Gulf, including the Patriot surface-to-air missile system. Now that know-how is proving invaluable to the Russian military against the Western-backed Ukrainians.

Battle-testing of Iranian drones in Ukraine against Western and Soviet-era air defense systems will undoubtedly also enhance their strategic use in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen and beyond, creating new security headaches for Israel and the wider Arab region.

Wreckage of an Iranian kamikaze drone, which was shot down in Odessa on September 25, 2022, amid Russia's invasion of Ukraine. (AFP)

Kamikaze drones pose a unique problem for modern militaries. Although advanced air defense systems are able to shoot down most Shaheds before they reach their intended target, a sufficient number will inevitably break through, raining down on Ukrainian apartment buildings and civilian infrastructure.

“The drones, which fly below the radar level of conventional air defense radar, are able to penetrate into Ukraine and cause more damage than the Russians would be able to do on their own,” DesRoches said.

Firefighters struggle to halt a blaze after a Russian attack using Iranian drones destroyed a Kyiv residential building. (AFP)

“A distributed drone attack against civilian infrastructure across a large country means that you will never have enough assets to ‘kill’ all the drones. It is far more expensive to defeat a drone than to launch one, and no one has enough equipment to protect every electrical substation in their country.”

He added: “By targeting them at civilian infrastructure, Russia is able to force Ukraine to dissipate its air defense assets and may be able, at some future point, to mass missiles and drones against a significant military target. So their impact has been significant.”

According to some analysts, as a result of prior Western inaction on the proliferation of Iran’s “conventional” weapons, as opposed to its nuclear ambitions, the regime’s kamikaze drones have now been exported to Europe, potentially posing a long-term security threat to the wider continent.

These analysts say that warnings to Western officials about the threat posed by Iran’s burgeoning drone program long went unheeded, allowing the regime to develop a large manufacturing base and trade network relatively unimpeded.

According to a UK defense intelligence report, published before the outbreak of war in Ukraine, various versions of the Shahed have been covertly deployed by the regime, including in an attack on the British-flagged oil tanker MT Mercer Street in 2021, which killed two, including a British civilian.

Prior to that attack, in September 2019, a volley of cruise missiles and kamikaze drones slammed into the Abqaiq and Khurais oil fields in Saudi Arabia. US Central Command believes the attack originated from Iran, crossing Iraqi airspace.

Wreckage of Iranian weapons used to attack Saudi Arabia's Khurais oil field and Aramco facilities in Abqaiq in 2019 are displayed at a Defense Ministry press conference. (AN file photo)

Following that attack, the American Enterprise Institute urged the US government to retaliate directly against IRGC drone facilities.

“Increasing American economic pressure has not deterred Iranian military or nuclear deal-violation escalation, and American military actions have only changed the precise shape of Iranian military escalation,” it said at the time.

The 2019 attack was also the first known instance of the combined use of cruise missiles and kamikaze drones to target a major energy facility, setting a dangerous precedent that foreshadowed the same tactic’s use in Europe against Ukraine’s power grid.

Western intelligence officials believe the Russian military is growing increasingly reliant on Shaheds as a substitute for more expensive and difficult-to-manufacture long-range precision guided intermediate range missiles, in part due to Western sanctions on Russia’s purchase of crucial electronic components.

This handout picture provided by the Iranian Army on May 28, 2022, shows Iranian military commanders visiting an underground drone base in an unknown location in Iran. (AFP)

Jason Brodsky, policy director at United Against Nuclear Iran, a New York-based bipartisan think tank, tweeted that the US and its allies had been “behind the curve” in tackling Iranian drone proliferation.

Although the Biden administration has announced fresh sanctions targeting Iranian arms manufacturers responsible for building Shaheds, Brodsky said the West squandered precious time that could have been spent nipping the Iranian drone threat in the bud.

“Washington and allies should have been laser focused on this a decade ago with respect to Iran. But the nuclear file dominated all,” he said, referring to the now largely defunct 2015 Iran nuclear deal, also known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

Omri Ceren, foreign policy adviser to US Senator Ted Cruz, was even more direct in his criticism of the Biden White House — for allowing Iran’s drone proliferation to reach this point and relying on Russia as the go-between with Iran on nuclear negotiations.

He tweeted: “Team Biden has made it a day 1 priority to weaken arms restrictions between Iran and Russia. They rushed to the UN to rescind the arms embargo vs Iran.”

European Union delegates attend talks to revive the Iranian nuclear deal. (AFP file)

Jake Sullivan, the administration’s national security adviser, recently acknowledges that Iran was likely “contributing to widespread war crimes” in Ukraine by actively providing a large number of combat drones and other weapons to the Russian military.

Nevertheless, serious questions remain over whether new sanctions on Iran’s drone manufacturing industry will come too little too late following years of a singular policy focus on reaching a nuclear agreement with Tehran.

Lessons provided by Israel, which has perhaps the most experience of neutralizing the Iranian drone threat, could offer US and European policymakers greater clarity, encouraging a more rapid response.

According to the Israeli defense think tank Alma, Iran’s extraterritorial Quds Force has established joint drone production facilities with a secretive division of Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia, known as Unit 127.

Military drones are displayed at a Hezbollah memorial landmark in the hilltop bastion of Mleeta, near the Lebanese southern village of Jarjouaa. (AFP file)

Satellite imagery provided by Alma shows what appear to be sprawling bases, which reportedly belong to Hezbollah, established in Al-Qusayr, Syria, near the Lebanese border, and in the far eastern Syrian desert city of Palmyra.

A number of airstrikes late last year attributed to Israel (although never officially claimed) directly targeted these bases and suspected joint drone manufacturing centers. Some analysts would like to see the West similarly target Iran’s drone technology at its source.

In the meantime, DesRoches said Ukraine’s Western allies must continue to provide air defense systems, while also helping to reinforce the structural integrity of critical infrastructure to withstand air attacks.

“Instead of starting with the threat and trying to defeat it, a state needs to start with its vulnerabilities and look to protect them, assuming that a drone will get through,” he said.

Hardening key energy facilities and developing a multilayered defensive plan based on this assumption was more realistic in meeting immediate needs in blunting the impact of Iranian drones, he said.

“Soldiers don’t like to think in these ways, and the profit a defense firm will make on sandbags is much less than will be made on a surface to air missile. But national security interests are best served by a vulnerability-based assessment of drone threats.”

It does appear the Biden administration is coming to the realization — belatedly — that Iran’s asymmetric drone capabilities and proliferation have become a global security threat.