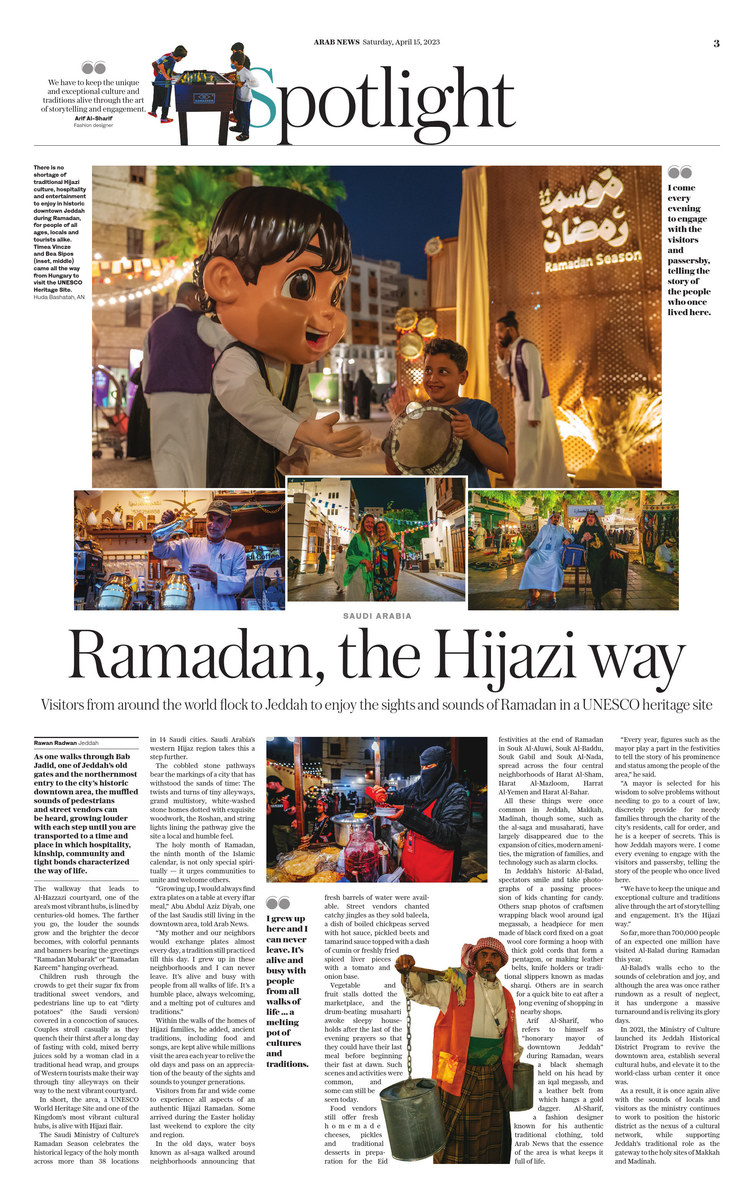

JEDDAH: As one walks through Bab Jadid, one of Jeddah’s old gates and the northernmost entry to the city’s historic downtown area, the muffled sounds of pedestrians and street vendors can be heard, growing louder with each step until you are transported to a time and place in which hospitality, kinship, community and tight bonds characterized the way of life.

The walkway that leads to Al-Hazzazi courtyard, one of the area’s most vibrant hubs, is lined by centuries-old homes. The farther you go, the louder the sounds grow and the brighter the decor becomes, with colorful pennants and banners bearing the greetings “Ramadan Mubarak” or “Ramadan Kareem” hanging overhead.

Children rush through the crowds to get their sugar fix from traditional sweet vendors, and pedestrians line up to eat “dirty potatoes” (the Saudi version) covered in a concoction of sauces. Couples stroll casually as they quench their thirst after a long day of fasting with cold, mixed berry juices sold by a woman clad in a traditional head wrap, and groups of Western tourists make their way through tiny alleyways on their way to the next vibrant courtyard.

Young boys join a crowd to get their share of traditional Ramadan sweets at a street in Jeddah's Al-Balad. (AN photo by Huda Bashatah)

In short, the area, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the Kingdom’s most unique cultural hubs, is alive with Hijazi flair.

The Saudi Ministry of Culture’s Ramadan Season celebrates the historical legacy of the holy month across more than 38 locations in 14 Saudi cities.

Saudi Arabia’s western Hijaz region takes this a step further. The cobbled stone pathways bear the markings of a city that has withstood the sands of time: The twists and turns of tiny alleyways, grand multistory, white-washed stone homes dotted with exquisite woodwork, the Roshan, and string lights lining the pathway give the site a local and humble feel.

The Hijazi neighborhoods in Jeddah's Al-Balad come alive every Ramadan night as people from all walks of life pour in to savor the food, sights and sounds of old. (AN photo by Huda Bashatah)

The holy month of Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, is not only special spiritually — it urges communities to unite and welcome others.

“Growing up, I would always find extra plates on a table at every iftar meal,” Abu Abdul Aziz Diyab, one of the last Saudis still living in the downtown area, told Arab News.

“My mother and our neighbors would exchange plates almost every day, a tradition still practiced till this day. I grew up in these neighborhoods and I can never leave. It’s alive and busy with people from all walks of life. It’s a humble place, always welcoming, and a melting pot of cultures and traditions.”

Men dressed in the traditional Hijazi attire relives the glory days of Jeddah at his nook and cranny in Al-Balad. (AN photo by Huda Bashatah)

Within the walls of the homes of Hijazi families, he added, ancient traditions, including food and songs, are kept alive while millions visit the area each year to relive the old days and pass on an appreciation of the beauty of the sights and sounds to younger generations.

Visitors from far and wide come to experience all aspects of an authentic Hijazi Ramadan. Some arrived during the Easter holiday last weekend to explore the city and region.

In the old days, water boys known as al-saga walked around neighborhoods announcing that fresh barrels of water were available. Street vendors chanted catchy jingles as they sold baleela, a dish of boiled chickpeas served with hot sauce, pickled beets and tamarind sauce topped with a dash of cumin or freshly fried spiced liver pieces with a tomato and onion base.

Characters portraying some of the most important figures in the historic days of Jeddah walk among the crowds as a means of telling a story. Al-saga, or waterboy, was an essential pillar of the community. (AN photo by Huda Al-Bashatah)

Vegetable and fruit stalls dotted the marketplace, and the drum-beating musaharti awoke sleepy households after the last of the evening prayers so that they could have their last meal before beginning their fast at dawn. Such scenes and activities were common, and some can still be seen today.

Food vendors still offer fresh homemade cheeses, pickles and traditional desserts in preparation for the Eid festivities at the end of Ramadan in Souk Al-Aluwi, Souk Al-Baddu, Souk Gabil and Souk Al-Nada, spread across the four central neighborhoods of Harat Al-Sham, Harat Al-Mazloom, Harrat Al-Yemen and Harat Al-Bahar.

All these things were once common in Jeddah, Makkah, Madinah, though some, such as the al-saga and musaharati, have largely disappeared due to the expansion of cities, modern amenities, the migration of families, and technology such as alarm clocks.

Food vendors are spread across Al-Balad's four central neighborhoods, offering traditional snacks and desserts. (AN photo by Huda Al-Bashatah)

In Jeddah’s historic Al-Balad, spectators smile and take photographs of a passing procession of kids chanting for candy. Others snap photos of craftsmen wrapping black wool around igal megassab, a headpiece for men made of black cord fixed on a goat wool core forming a hoop with thick gold cords that form a pentagon, or making leather belts, knife holders or traditional slippers known as madas sharqi. Others are in search for a quick bite to eat after a long evening of shopping in nearby shops.

Arif Al-Sharif, who refers to himself as “honorary mayor of downtown Jeddah” during Ramadan, wears a black shemagh held on his head by an iqal megassb, and a leather belt from which hangs a gold dagger. Al-Sharif, a fashion designer known for his authentic traditional clothing, told Arab News that the essence of the area is what keeps it full of life.

“Every year, figures such as the mayor play a part in the festivities to tell the story of his prominence and status among the people of the area,” he said.

Fashion designer Arif Al-Sharif, right, plays the role of the mayor during Ramadan. (AN photo by Huda Al-Bashatah)

“A mayor is selected for his wisdom to solve problems without needing to go to a court of law, discretely provide for needy families through the charity of the city’s residents, call for order, and he is a keeper of secrets. This is how Jeddah mayors were. I come every evening to engage with the visitors and passersby, telling the story of the people who once lived here.

“We have to keep the unique and exceptional culture and traditions alive through the art of storytelling and engagement. It’s the Hijazi way.”

So far, more than 700,000 people of an expected one million have visited Al-Balad during Ramadan this year.

Two Hungarian tourists, college student Timea Vincze and her cousin Bea Sipos, a financial analyst from Budapest, told Arab News that they have visited Al-Balad three times during their 10-day stay in the Kingdom.

Timea Vincze and Bea Sipos came all the way from Hungary to visit the UNESCO Heritage Site. (AN photo by Huda Bashatah)

“I didn’t expect it to look so nice; it’s very authentic and very different from Europe, as we don’t really have these kinds of downtowns … it’s amazing,” said Sipos.

She said her favorite part of Jeddah is “definitely the old town. The vibe here is really unique, so all these buildings (are) amazing. It’s totally empty during the day; I think that’s a good thing in Ramadan for us so we can visit when it’s totally empty, and at night it’s so busy with so many people.”

Vincze said: “It’s really beautiful here and I just can’t get enough. I think the buildings are very interesting, very different from what we have in my country or in Europe. It’s beautiful. It’s part of UNESCO and I hope it will be the same in a few years because it’s very unique and beautiful.

“The people were very nice to us; many would come (over) and just smile at us. I have never seen this kind of kindness in another country, and they’re also helpful, asking us where we’re from and telling us to enjoy our time. That’s very heartwarming.”

Locals relive the good old days as Al-Balad undergoes a massive turnaround after decades of neglect. (AN photo by Huda Bashatah)

Al-Balad’s walls echo to the sounds of celebration and joy, and although the area was once rather rundown as a result of neglect, it has undergone a massive turnaround and is reliving its glory days.

In 2021, the Ministry of Culture launched its Jeddah Historical District Program to revive the downtown area, establish several cultural hubs, and elevate it to the world-class urban center it once was.

As a result, it is once again alive with the sounds of locals and visitors as the ministry continues to work to position the historic district as the nexus of a cultural network, while supporting Jeddah's traditional role as the gateway to the holy sites of Makkah and Madinah.