DUBAI: The fighting in Sudan, now in its second month, shows no sign of ending, and is contributing to Africa’s swelling number of people displaced by conflicts. What began as a feud between two factions in Khartoum had spread to other regions, claiming lives, shutting down public life, destroying infrastructure and sparking a humanitarian crisis characterized by shortages of medicine, fuel and food.

Now, Sudan’s neighbors, many of which have for decades dealt with their own conflicts, instability and humanitarian challenges, are calling for an end to the fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces, or SAF, and the paramilitary group Rapid Armed Forces, or RAF, before it spills across borders and engulfs them.

Even prior to the eruption of violence in Khartoum on April 15, efforts were underway to prevent simmering tensions between the rival Sudanese factions from turning into an all-out conflict.

A view shows black smoke and fire at Omdurman market in Omdurman, Sudan, May 17, 2023. (Screengrab/Reuters)

“One week before the crisis, our chief negotiator went to Khartoum to meet with the chairperson of the Sovereign Council, Gen. Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, and the then-deputy chairperson of the Sovereign Council, Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo,” Deng Dau Deng Malek, the acting minister of foreign affairs of South Sudan, told Arab News in a recent Zoom interview from Juba.

He said the last-ditch diplomatic efforts by the South Sudanese government were aimed at ironing out the kinks of the planned transition to a civilian-led government in Khartoum.

Among the many roadblocks in the path of a peaceful settlement was the thorny issue of the integration of Dagalo’s RSF into the military, an issue which lit the fuse of Sudan’s current conflict.

Malek declined to assign blame exclusively to one side or the other, saying merely that, in some ways, the conflict in Sudan was inevitable.

He said that while the world was largely caught off guard by the eruption of fighting in Sudan, his own country’s experience with conflict resolution and peacemaking equipped him with the foresight to predict that a war was inevitable within the borders of its northern neighbor.

Smoke rises above buildings in southern Khartoum on May 19, 2023, as violence between two rival Sudanese generals continues. (AFP)

In South Sudan, Malek recalled, “there was a provision that provided (for) two armies in one country, which was a really big mistake at that time. So, once the two armies came to Juba, it led to a war in July 2016.”

He added: “We were very much aware that there is always a problem to agree to two armies in one country, whatever the nature, whatever the standing of that army.

“So, yes, the situation in Sudan was known to be really going toward that.”

Even though the South Sudan government expected tensions over Sudan’s power-sharing agreements, Malek acknowledged that it was unprepared for the crisis that arose on April 15.

“We were not very prepared (for) that kind of scale of war (that) would blow out like that,” he said.

“We knew it would be a limited engagement, with a very practical coming together for the SAF and RSF — (but) not to go the way they have gone so far.”

INNUMBERS

- 705 People killed in fighting since April 15 (WHO).

- 5,287+ Those who have suffered injuries (WHO).

- 1.1m Displaced internally or into neighboring countries.

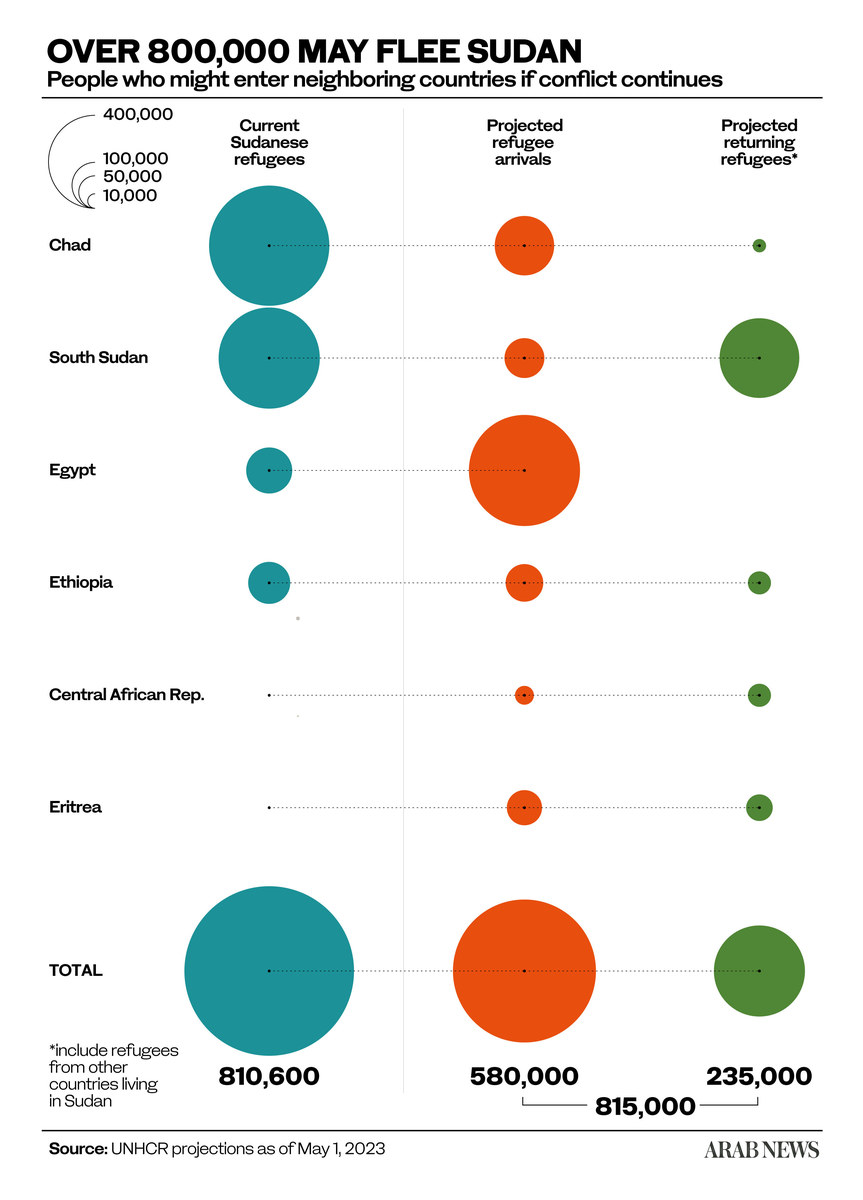

With neither Al-Burhan nor Dagalo willing to call a timeout, South Sudan and other neighbors of Sudan are bracing themselves to deal with the repercussions. Hundreds of thousands have already fled the strife-torn country, with the UN refugee agency, or UNHCR, predicting that the fighting would force 860,000 people to flee.

“This is one of our biggest concerns, the spillover,” Malek said.

Sudan shares a border, in order of length, with South Sudan, Chad, the Central African Republic, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Libya.

The UNHCR has envisioned three scenarios: Sudanese refugees fleeing to neighboring countries; refugees hosted by Sudan returning home; and refugees hosted by Sudan moving to other neighboring countries.

“At this particular stage, there are (relatively) very few people who have moved to South Sudan,” Malek said, alluding to the fact that while the majority of those displaced by the fighting in Sudan have fled to Egypt and Chad, South Sudan has received 58,000 people.

Of these, according to Malek, only 8,000 are Sudanese. Incidentally, prior to the fighting that began last month, Sudan itself was home to more than a million refugees — mostly from South Sudan — as well as more than 3 million IDPs, or internally displaced persons.

With the security situation in Sudan no longer suitable for those who once sought shelter there, many former refugees are now twice displaced, returning to their countries of origin or seeking safety elsewhere.

Aside from dealing with waves of refugees and IDPs, Sudan’s neighbors will also have to face up to the wide-ranging consequences of the conflict.

“(South Sudan’s) economic viability is also dependent on the pipeline, the oil that passes through the territory of the Republic of Sudan,” Malek said.

South Sudan’s crude oil exports reached around 144,000 barrels per day early this year, with the majority of this being piped to Sudan’s Red Sea coast. Now, the price of oil has fallen from $100 per barrel to $70.

Though oil continues to flow through the vital pipeline, the conflict has threatened oil revenues as well as the world’s energy supply.

“Our message to both of the (Sudanese factional) leaders and those who are fighting — (something) we will say to both — is this: We need protection of this pipeline because it is the viability of the economy of (our) country,” Malek said.

United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) personnel use an excavator to repair the dykes in Bentiu on February 8, 2023. Four straight years of flooding, an unprecedented phenomenon linked to climate change, has swamped two-thirds of South Sudan. (AFP)

The combined blow of economic setbacks and influx of displaced people threatens to overwhelm Sudan’s neighbors in northern and central Africa, most of whom are impoverished and unstable themselves.

South Sudan is still reeling from a six-year civil war which ended just three years ago. That human-made catastrophe was followed by severe floods, which continue to this day and have pushed the country’s roughly 12 million residents, more than 2 million of whom are internally displaced, to the brink of starvation by making agricultural lands inaccessible.

“The UN too is overwhelmed by our own situation,” Malek said, adding that “UN agencies have been under very serious stress.”

As a result of the many overlapping crises, three-quarters of South Sudan’s population is dependent on humanitarian aid, according to UNHCR data.

Nearly a million people were affected by South Sudan flooding. (AN photo by Robert Bociaga)

Malek pointed out that South Sudan had been hosting 340,000 Sudanese in several camps in the Upper Nile state. “We are coordinating with the UN agencies to be able to address the situation of those who are returning and the (people who) are crossing (into South Sudan) from Sudan,” he said.

“Particularly now, when we are talking about the northern part of South Sudan, to which the refugees and IDPs are returning. The infrastructure there is a challenge. Also, Sudan was the only way that we received commodities from Port Sudan, and now (there is) a very big challenge as to whether that will continue to work.”

Looking to the future, Malek said international support is vital to limiting the damage being caused by the crisis in Sudan and preventing its neighbors from being destabilized by a humanitarian catastrophe.

In this context, Malek said UN agencies would have to “provide the necessary support to localities inside Sudan” so that they can stop the free movement of fighters.

Provision of water, sanitation and hygiene to a growing number of IDPs in South Sudan has become an alarming issue. AN photo by Robert Bociaga)

He cautioned once more that if “the insecurity and war spread out of Khartoum to the region, the situation will be difficult for all the neighboring countries.”

Turning to the problems that beset South Sudan, Malek noted that while the US has long been an ally, supporting the world’s youngest nation through times of conflict — from the 2011 independence referendum through to the 2018 peace talks in Kenya — work still needs to be done for the sanctions and arms embargoes imposed on the country to be lifted.

“We have said that now we have to open up a new page with the United States of America and for us to work together,” he said. “Of course, they have issues with (our) human rights issues, issues of democracy, issues of corruption, or issues of governance.”

“South Sudan is under sanctions and the US is the penholder on these particular sanctions (at the UN). There are about five benchmarks that (the US wants) to see. If these five benchmarks are met by the government of South Sudan, then we will be able to get out of sanctions and the arms embargo.”