LONDON: On July 16, the people of Damascus awoke to the shocking news that fire had torn through the city’s historical district overnight, destroying the palace of Abdulrahman Pasha Al-Yusuf in the Old City’s Souk Sarouja.

The blaze had started in a house adjacent to the palace at around 3 a.m. local time before quickly spreading, according to state media agency SANA. Local reports suggested it was sparked by an electrical fault, but social media users have speculated it may have been arson.

The fire also partially damaged Al-Azm Palace, which contains the Center for Historical Documents, and swept through several neighboring homes, stores, and workshops along nearby Al-Thawra Street.

It took firefighters more than four hours to bring the blaze under control. In that time, immense damage had been caused to the Old City, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the world’s oldest inhabited cities.

Recent fires in the Old City of Damascus, a UNESCO World Heritage site, have caused irrevocable damage. (Supplied)

For a city as ancient as Damascus, “Souk Sarouja is relatively new,” Sami Moubayed, a Damascus-based historian, writer, and former visiting scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center, told Arab News.

The neighborhood is approximately 800 years old and was built by the Mamluks to house soldiers.

Moubayed said: “By the mid-19th century, Sarouja grew to house some of Damascus’ finest homes.”

The district was known as Little Istanbul because some of the most senior officials from the Ottoman capital resided there and because its grandeur bore a striking resemblance to the city.

“During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it acquired its political significance because a handful of senior Arab officials at the Imperial Court in Istanbul established their palaces within its confines,” Moubayed added.

Among those prominent historical figures was Abdulrahman Pasha Al-Yusuf, the emir of Hajj, who was also the deputy head of the Pan-Syrian Congress before becoming president of the Shoura Council. It was Al-Yusuf’s home that was destroyed in the July 16 fire.

The fire also partially damaged Al-Azm Palace, which contains the Center for Historical Documents, and swept through several neighboring homes, stores, and workshops along nearby Al-Thawra Street. (Supplied)

“(Al-Yusuf’s house) lost its political significance following his assassination in 1920, but its cultural and social relevance remained,” Moubayed said.

Another notable figure in the history of Damascus was Muhammad Fawzi Pasha Al-Azm, father of Khalid Al-Azm, whose house was adjacent to Yusuf’s and which was partially damaged in the blaze.

“Al-Azm was named Ottoman minister of awqaf in 1912 but, prior to this, he was head of the Damascus municipality, and later was elected president of the Syrian National Congress, Syria’s first post-Ottoman parliament.

“After Muhammad Fawzi Pasha Al-Azm passed away in 1919, his son Khalid, who formed five governments in the modern history of Syria, continued to live in the palace,” Moubayed added.

“After Muhammad Fawzi Pasha Al-Azm passed away in 1919, his son Khalid, who formed five governments in the modern history of Syria, continued to live in the palace,” Moubayed added.

Also among Sarouja’s historically notable inhabitants was Ahmad Izzat Pasha Al-Abid, second secretary and confidant of Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II.

Moubayed said: “The house maintained its political relevance during the life of his son Muhammad Ali Al-Abid, who upon becoming the Syrian Republic’s first president in 1932, chose to rule from Sarouja for a brief period. He then moved to Al-Abid Palace in the Muhajirin district.”

Sarouja was fortunate to survive previous disasters.

“In 1945, Sarouja was impacted by France’s bombardment of Damascus. On May 29, 1945, Jamil Mardam Bey, who was (Syria’s) foreign minister and acting premier, was at government headquarters when the French aggression reached its vicinity.

“He fled with other officials from Zukak Ramy at sunset and sought refuge in Khalid Al-Azm’s house in Sarouja as there was an arrest warrant against them. This same house was partially damaged on Sunday.

“The house in 1945 provided sanctuary for over 100 people. When the French found out that Mardam Bey was in Al-Azm’s house, they began to heavily bomb Sarouja,” Moubayed added.

Although Sarouja has bounced back before, the July 16 fire damage was extensive and will leave a lasting scar, both on the district and its residents.

Loujein Haj Youssef, a Paris-based journalist, said the sight of Sarouja engulfed in flames brought tears to her eyes. She grew up and spent her early adulthood in Damascus and noted that the scale of the destruction was heartbreaking.

“I thought Damascus was an eternal city. Never have I thought, for instance, to take a picture in Khalid Al-Azm’s palace, an exquisite architectural masterpiece, although I regularly spent a lot of time there.

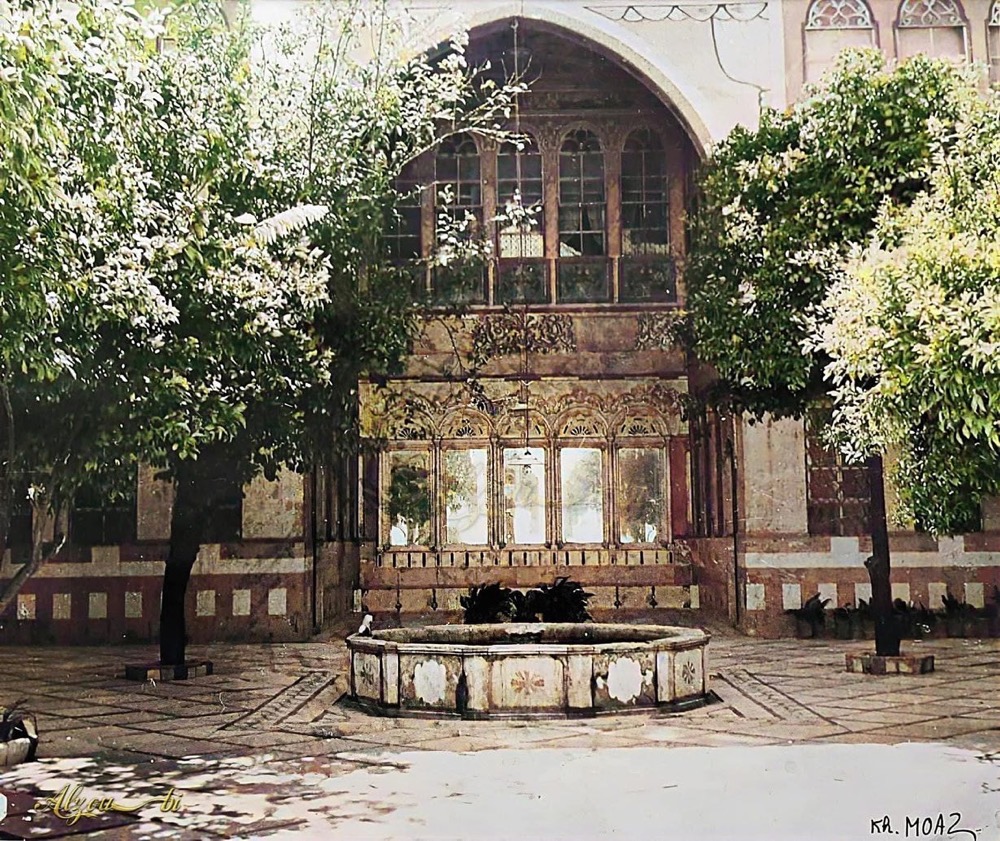

Al-Yusuf Palace before the fire. (Supplied)

“Our recent memory of Damascus is lost. One day, we will search our memory for pictures of the Old City but will only find that these have been replaced by images of ashes and bare cement walls,” Youssef added.

Marwah Morhly, a Damascene writer now residing in Turkiye, felt a part of her identity was lost to the flames.

She said: “Not only did the fire burn my city’s history, but it also burned our youth, the laughter that echoed in the ancient alleyways, and our early taste of freedom, when we first left the confines of school and university.

“Sarouja was a meeting place for lovers and politicians, laughter and tears, and the dreams of our youth. It is now a place that burns us on the inside, as if our hearts are not wearied enough by all the fires raging within.”

Despite the affection that many Syrians have for the district, it has long been neglected. In 2013, UNESCO placed the Ancient City of Damascus, which incorporates Sarouja, on its list of World Heritage in Danger.

Al-Yusuf’s house lost its political significance following his assassination in 1920, but its cultural and social relevance remained, said Sami Moubayed, a Damascus-based historian and writer. (Supplied)

Moubayed said: “Sarouja district declined, as did the rest of the Old City, because, with the onset of French rule, many Damascene families moved to apartments.

“Districts with modern housing, such as Al-Shuhadaa, Al-Abid, and Shaalan, emerged, and people abandoned old houses for many reasons, including difficult access and maintenance and the inconvenience of having several families live in one place.

“Women also progressed and started demanding to have residences of their own. People started owning cars, and the (narrow) alleyways are difficult to navigate.”

Moubayed pointed out that there was little interest in restoring the city’s old houses until the 1990s, when work began to salvage and repurpose the Christian districts of Bab Touma and Bab Sharqi, where boutique hotels and restaurants have sprung up.

It took firefighters more than four hours to bring the blaze under control. (Supplied)

“Souk Sarouja, not receiving the same level of attention, gradually deteriorated into a run-down, lower-income area with small cafes, in contrast to other parts of the Old City, which are renowned as the upper crust, hosting prestigious hotels like Talisman and Beit Al-Mamlouka,” he added.

Unless the area gains the same level of interest, what remains of Sarouja’s historic buildings may soon be lost to time altogether.