LAHORE: Tortured and imprisoned by Islamist militants for nearly five years, Shahbaz Taseer says he forgot how it felt to smile. Now, he is determined to live without fear.

The scion of a prominent business and political family, his abduction in August 2011 was one of Pakistan’s most high-profile.

“I remember how alien that feeling was — of smiling,” Taseer, 39, told AFP in an interview. “I didn’t laugh for a very long time.”

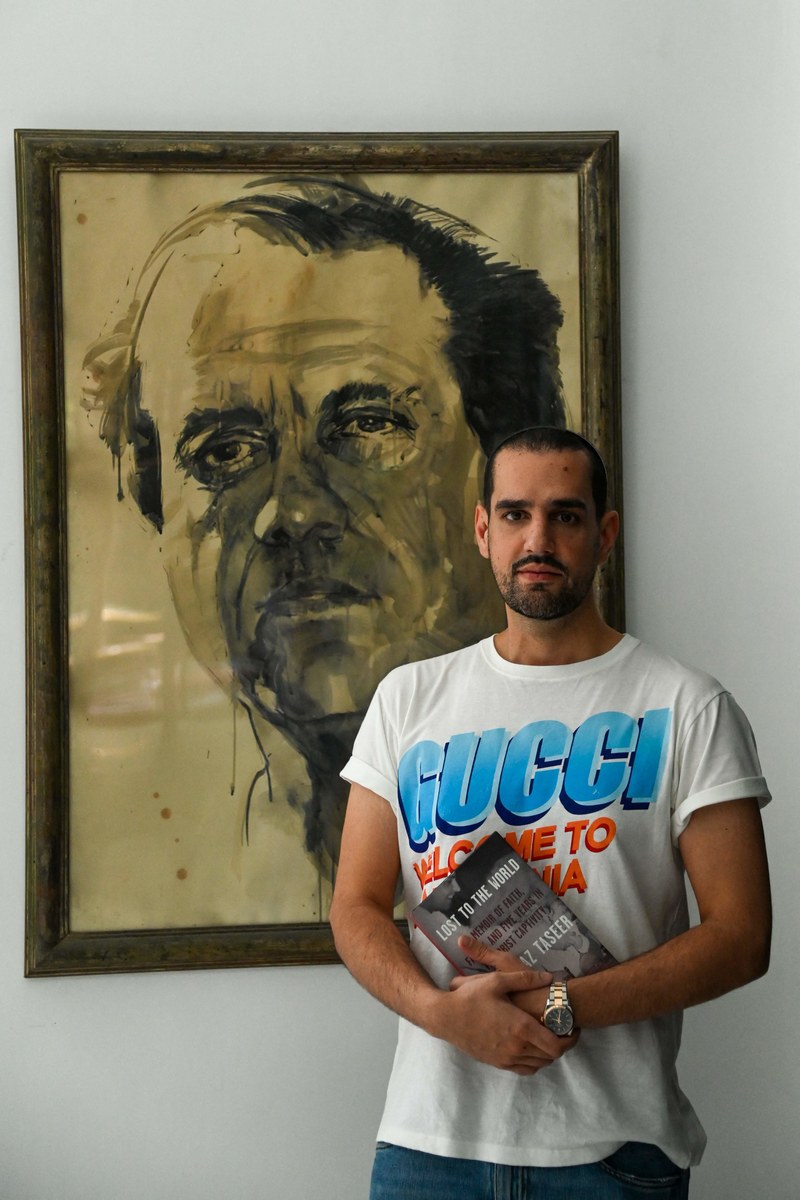

This photo taken on July 19, 2023 shows Shahbaz Taseer posing with a painting of his late father Salmaan Taseer, former governor of Punjab province, at his residence in Lahore, Pakistan. (AFP)

The release of his book “Lost to the World” last November came as violence and extortion were rising along Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan, following the withdrawal of foreign troops and the return of the Taliban to power in Kabul two years ago.

Taseer was abducted near his Lahore home, months after his father Salmaan — then governor of Punjab province — was shot dead by a bodyguard for supporting changes to the country’s strict blasphemy laws.

Salmaan had supported Aasia Bibi, a Christian woman accused of blasphemy whose case drew global coverage and put the governor and his family in the crosshairs of Islamist extremists.

Taseer was abducted by the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) — a group blamed for several high-profile attacks in Pakistan, including the 2014 storming of Karachi airport that killed dozens.

Drugged with ketamine, Taseer was disguised in a burqa and smuggled through roadside checkpoints between Lahore and Mir Ali — a town in North Waziristan district, a long-time haven for militants along the border with Afghanistan.

Believed by Pakistan’s military intelligence to be among the area’s most brutally violent groups, the IMU sought a huge ransom and the release of nearly 30 detainees — demands Taseer says could not be met.

Taseer’s book depicts his primary captor — Muhammad Ali — as a sadistic megalomaniac. On his orders, Taseer had his nails pulled out and his mouth sewn shut.

“They started torturing me in the most horrific manner and making videos,” Taseer said.

The videos were sent to his family, an act Taseer described as “very dehumanizing and very humiliating.”

“You’re not torturing one person, you’re touching so many people.”

The once-privileged Taseer was chained to the floor and fed only goat fat and bread for more than six months.

“I didn’t even feel human anymore, and human emotions, I couldn’t even relate to them,” he said.

“I felt like an animal.”

In 2015, the Uzbek group clashed with the Afghan Taliban, who took custody of Taseer after defeating his abductors.

Months later, in February 2016, he was set free after his Taliban captors learned that one of their senior leaders had previously helped the Pakistani government attempt to negotiate his release from the Uzbek militants.

For a week, he journeyed from the Afghan province of Uruzgan to a town in southwestern Pakistan, where he was able to phone his mother from a roadside restaurant.

“The first thing I asked for was a pay phone, and (the owner) said, ‘Pay phones have been obsolete for two, three years.’“

By chance, Taseer’s release came the same day his father’s murderer was executed: February 29, 2016.

The attacks on Taseer’s family exposed divisions in Pakistani society related to the blasphemy laws that he says have only broadened.

“I see some of these (anti-blasphemy) extremist groups... have evolved into now political parties,” he said. “And that worries me.”

“I don’t want (my children) to grow up in an intolerant society. I want them to be able to ask questions... without being killed.”

Taseer says Pakistan “still has a long way to go” to become a society tolerant of diversity of thought and religion.

He maintains, however, that the sources of some of the country’s biggest problems — “militancy, extremism and religious extremist groups” — hold little legitimate power and are a minority.

“Maybe (Pakistanis are) a conservative people because of our religion. But that doesn’t mean that we’re extremists,” he says.

“We have suffered because of militancy, and extremist militancy, like very few countries in the world.”

Despite cementing his faith while in captivity, Taseer has not set foot in a mosque in Pakistan since his release, based on security recommendations.

Still, he says he does not want to leave the country and is determined not to live in fear.

“You only live once, and you should live on your own terms,” he said.