KARACHI: The newsstand of Rashid Rehman buzzed with energy as a large crowd gathered around it on the bustling II Chundrigar Road in southern Pakistani port city of Karachi.

On the fateful day of October 12, 1999, the 62-year-old recalls, a zamima, a special newspaper supplement, had come out, headlined as “Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif sacks General Pervez Musharraf,” with the hawker forced to stash money in his shirt as it became impossible for him to channel it into the money box amid an influx of curious customers.

Rehman, standing at his quiet stall today, reminisces the golden days when newspapers had their own way of breaking extraordinary news developments in the South Asian country, which would skyrocket his sales.

“It was fun to work in those days,” he told Arab News this week.

“Long queues of people would form, and big cars would pull up, [the occupants] handing over money without bothering about the change. They would simply drive off, [saying] we just want the zamima.”

The still image taken from a video on August 10, 2023, shows people standing at a newsstand in Karachi, Pakistan. (AN Photo)

Rehman shared that newspaper circulation departments would alert him and other hawkers every time a zamima was to be published.

The 62-year-old said there was a time when two such supplements were published in a day, while the one that brought him the highest sales figures was about the hanging of former Pakistan prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto by then military ruler Zia-ul-Haq on April 4, 1979.

Mehmood Sham, a veteran journalist who began his career from Lahore in early 1960s, says zamimas heralded fresh news even before the birth of Pakistan. Street hawkers, he recalls, would shout catchy phrases to attract people’s attention.

They would shout ‘Yeh Taza Khabbar Aai Hai, Khizar Hamara Bhai hai (A fresh news has arrived, Khizar is our brother),’ narrating tales of shifting political allegiances of Khizar Hayat, a Unionist Party leader and the chief minister of Punjab in British India, according to Sham.

“Someday he (Hayat) would support the Muslim League and someday he would oppose it. So, he (hawker) would shout ‘Yeh Taza Khabbar Aai Hai, Khizar Hamara Bhai hai’,” Sham told Arab News.

“And then declare ‘Yeh Taza Khabar Aai hai, Khizar se Hamari Larai hai (This fresh news has arrived, we have a fight with Khizar)’.”

Muhammad Saleem Khan, an avid reader, reminisces about the era when zamimas used to be a communal badge of honor.

“The enthusiasm for zamima was such that people would eagerly read it and share with others, excitedly announcing that a new zamima had been published,” he recalled.

“’Have you heard the news? We read it in zamima!’ was a common reference among people.”

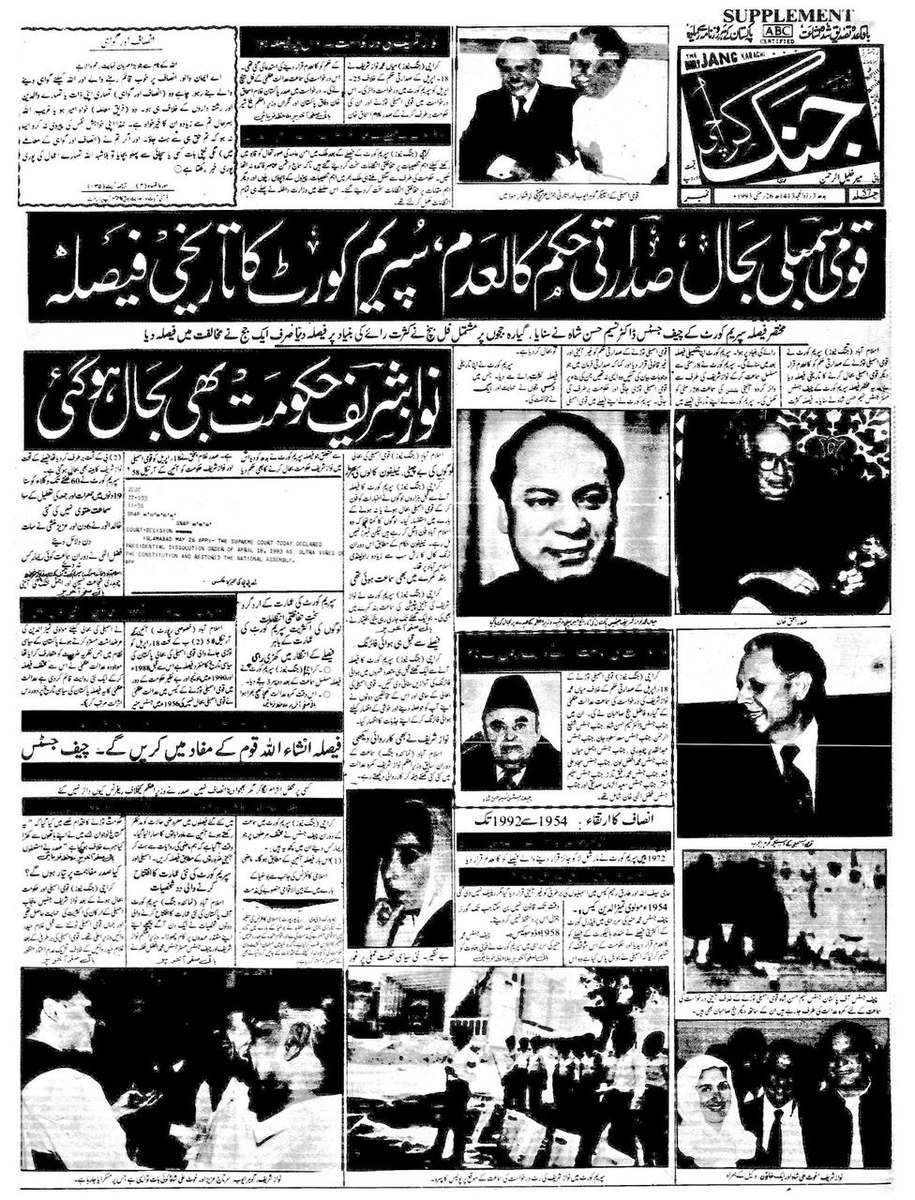

The still image taken from a video on August 10, 2023, shows a print of an old copy of a zamima, a special newspaper supplement, in Karachi, Pakistan. (AN Photo)

Nowadays, a breaking news is incessantly flashed on television screens “throughout the day,” according to Khan. Zamimas in Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city and commercial hub that has a history of political and ethnic violence, would be mostly about strikes and the law-and-order situation.

“Now people read the breaking news daily. After two minutes, they read it on Internet,” Khan said.

As technology reshapes the news landscape, Rehman’s stall stands as a poignant relic on Karachi’s II Chundrigar Road, echoing the days of zamima dominance.

The 62-year-old hawker believes if the era of zamima were in place at the time of ex-premier Imran Khan’s sentencing in a graft case on August 5, it would sell like hotcakes.

“One can only imagine the significant sales it would garner,” Rehman said, remembering the bygone era.

The skillfully crafted headlines for relatively minor events, such as train and bus accidents, in zamimas would also result in substantial sales, according to Rehman.

Sham, who went on serve as the editor of Pakistan’s most circulated Urdu-language daily Jang, noted his newspaper published the last zamima on October 12, 1999, when former premier Nawaz Sharif dismissed then army chief, General Musharraf, but the latter subsequently ousted the former from power through a military coup.

“As I recollect, this event marked the final issuance of a zamima by Jang. I distinctly remember that Nasir Baig Chughtai was the news editor,” Sham told Arab News.

“I am reminded that this news came to light around 5 o’clock when his dismissal took place. When he (Chughtai) was making the headlines of zamima, at that moment, I said that this headline might not find its way into the morning newspaper.”

A zamima, a special newspaper supplement published on May 26, 1993, shows the news regarding the reinstatement of Muhammad Nawaz Sharif to the position of Prime Minister, following his government's dismissal in April 1993. (AN photo)

Sham said it precisely happened the way he had thought, adding unlike today’s constant stream of breaking news, not every news would make it to zamima.

“When the newspaper decided to publish a zamima, it would be news that could impact the entire country or affect the city from where it would be published,” the seasoned journalist said.

With the influx of TV channels that have already taken over breaking news from newspapers and the advent of social media, Rehman said several newsstands in his vicinity have shut down.

“Many say that ‘we will take it from the Internet’,” said a dismal Rehman. “People no longer grasp newspapers in their hands. Instead, they hold onto mobile phones.”