LONDON/AMSTERDAM: Along Lebanon’s southern border with Israel, stretching from coastal Naqoura in the west to Houla in the east, adjacent to the UN-administered Blue Line, visitors have long been greeted by a striking vista of green-blanketed mountains.

Today, however, whole swathes of this landscape, covered with oaks, pines, and trees abundant with apples and olives, have been left barren — scorched by white phosphorus, allegedly rained upon the hills by Israeli forces to deprive Hezbollah militants of tree cover.

Since the Hamas attack on southern Israel on Oct. 7, Hezbollah fighters sympathetic to the Palestinian militant group have been trading fire with Israeli forces along the border, raising fears of a new front in the Gaza conflict and a wider regional escalation.

Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, gave a live-streamed speech on Friday in Beirut’s Ashura Square in which he praised the Oct. 7 attack, but stopped short of announcing that his followers had fully joined the Israel-Hamas war.

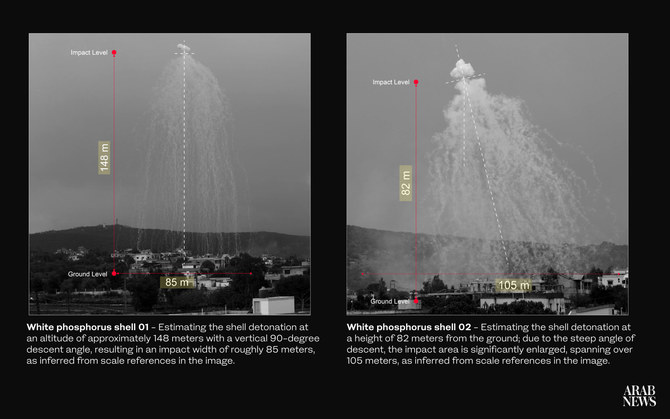

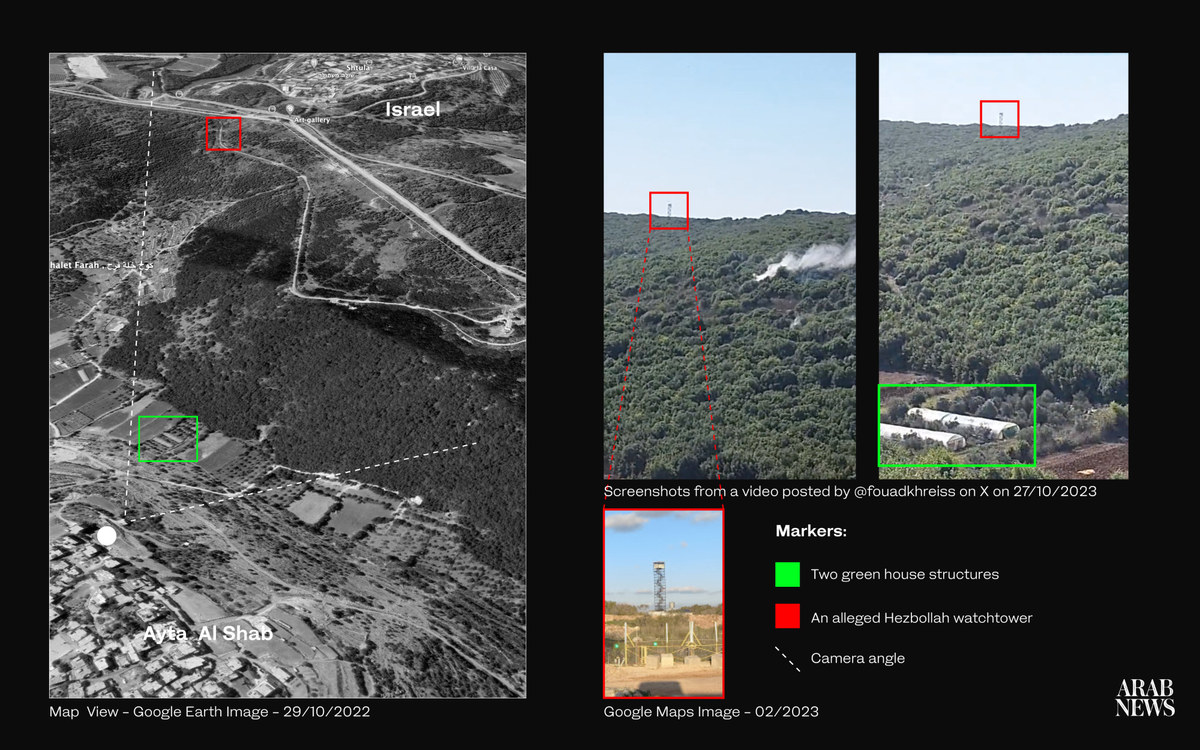

Geolocation Analysis: Identifying the impact sites of two white phosphorous attacks on civilian areas, using photographic evidence cross-referenced with online images and satellite imagery for precise geolocation.

He did however warn that fighting on the Lebanon-Israel border would not be limited to the scale seen so far and that further escalation in the north was a “realistic possibility.”

Despite urgent appeals for calm from the UN Interim Force in Lebanon stationed along the Blue Line, marks of these initial skirmishes between Israel and Hezbollah are already visible on the landscape.

About 40,000 hectares of green field and agriculture — including 40,000 olive trees — have been burned on the Lebanese side of the border in recent weeks, according to sources close to Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment.

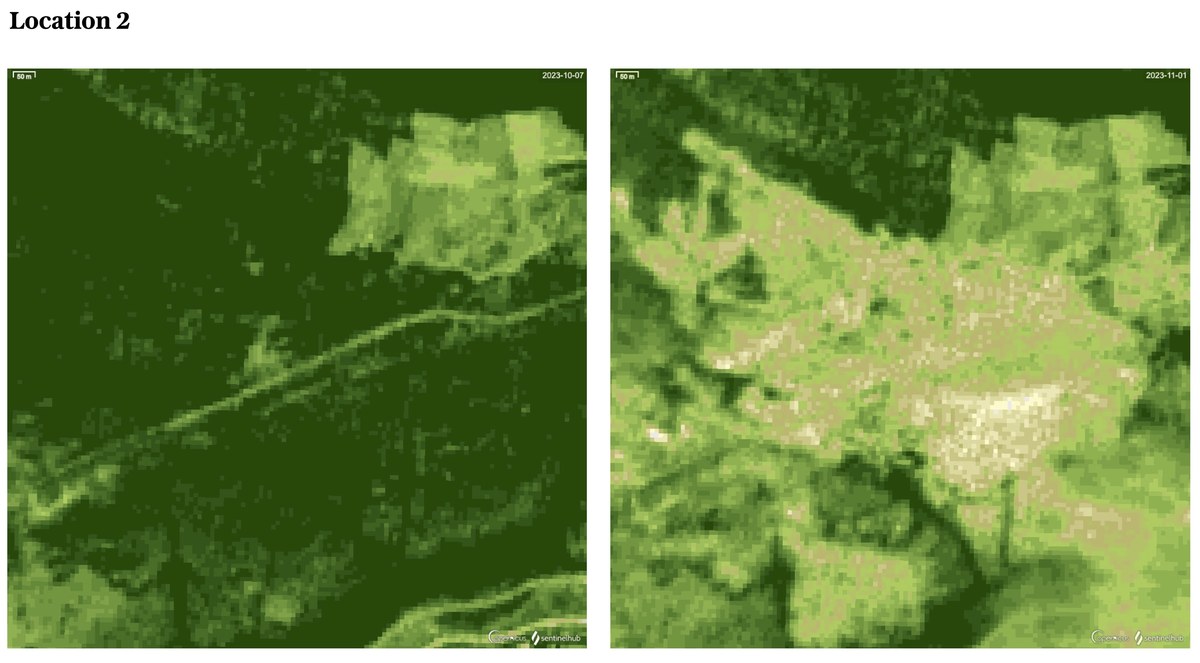

Key Map Overview: Locations in the Naqoura region marked to show the sites of before and after imagery, capturing the areas affected by fires resulting from Israeli shelling.

Before and After: On the left is an image captured on Oct. 7, 2023 via Sentinel-2 L2A, utilizing the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) to highlight vegetation health before the incident. The second one was captured on Nov. 1, 2023 via Sentinel-2 L2A, using NDVI to illustrate the change in vegetation health before the incident.

Before and After: The image on the left, captured on Oct. 12, 2023, and obtained via Sentinel-2 L2A, shows vegetation health through NDVI prior to the shelling. The second one, from Nov. 1, 2023, secured via Sentinel-2 L2A, depicts the impact on vegetation health following the shelling, as indicated by NDVI changes.

“They really want to burn everything in front of them so that they see more clearly. And they won’t allow Hezbollah or the Lebanese army to hide behind those greeneries or bushes,” Najat Aoun Saliba, a Lebanese lawmaker and chemistry professor at the American University of Beirut, told Arab News.

According to human rights monitor Amnesty International, the Israel Defense Forces have been using shells containing white phosphorus — an incendiary weapon — against targets inside Lebanon.

“It is beyond horrific that the Israeli army has indiscriminately used white phosphorus in violation of international humanitarian law,” Aya Majzoub, deputy regional director for the Middle East and North Africa at Amnesty International, said in a report published on Tuesday.

“The unlawful use of white phosphorus in Lebanon in the town of Dhayra on Oct. 16 has seriously endangered the lives of civilians, many of whom were hospitalized and displaced, and whose homes and cars caught fire.”

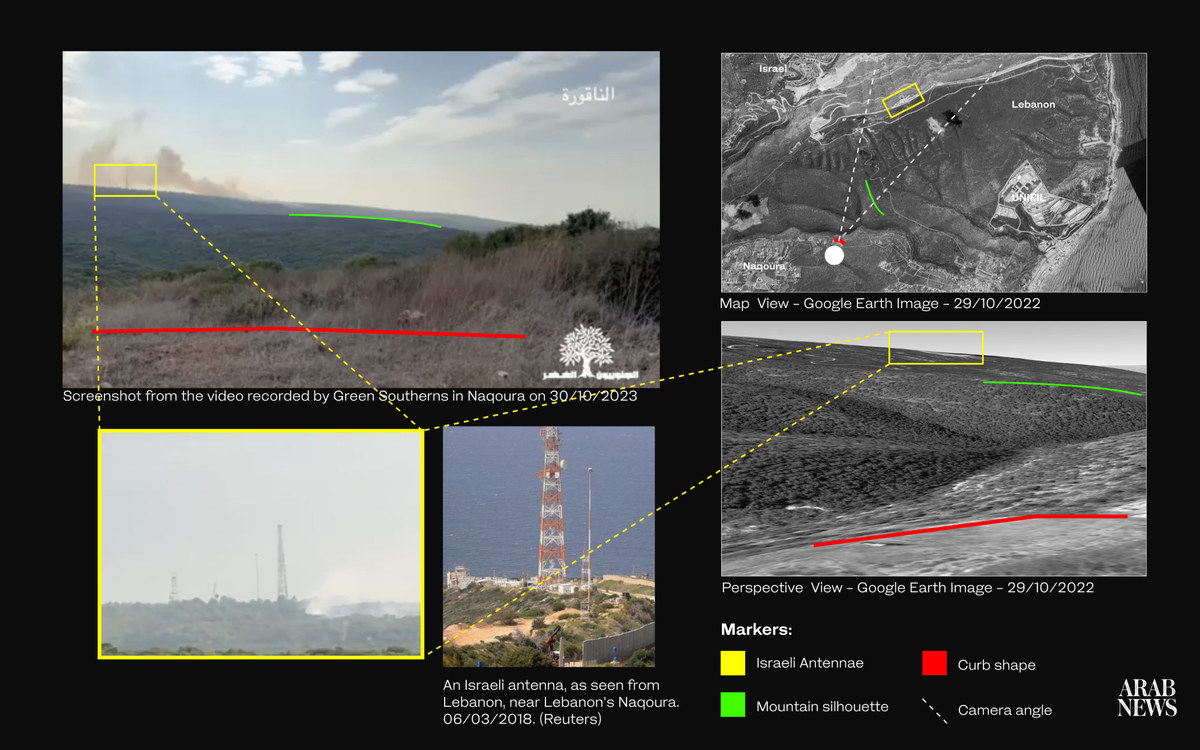

Video footage provided by the GreenSoutherns captures the extensive fires in the Naqoura region, showcasing the aftermath of the recent shelling.

Geolocation Analysis: Tracing the source of fires in Naqoura, Lebanon, by aligning markers from the video with online image databases and satellite imagery for accurate localization.

Arab News has independently verified footage and images provided by environmental activists and residents using advanced open-source intelligence techniques. This process involves geolocation of the images and videos, time-series analysis to confirm their recency and cross-referencing with open-access satellite imagery.

By overlaying these images on satellite maps and analyzing the color spectrum for events like fires, Arab News can authenticate the location, timing, and events captured in the images, ensuring the information’s accuracy and authenticity.

The Israeli military maintains that it uses the incendiaries only as a smokescreen, and not to target civilians. In a statement to the Associated Press in October, it said the main type of smokescreen shells it uses “do not contain white phosphorus,” but it did not rule out its use in some situations.

White phosphorus, when exposed to oxygen in the air, burns at extremely high temperatures, illuminating targets concealed in darkness. When burning, it also creates a dense white cloud that militaries often use to mask maneuvers, but which can be lethal if inhaled.

People who have been exposed to white phosphorus “suffer respiratory damage, organ failure and other horrific and life-changing injuries, including burns that are extremely difficult to treat and cannot be put out with water,” according to the Amnesty report.

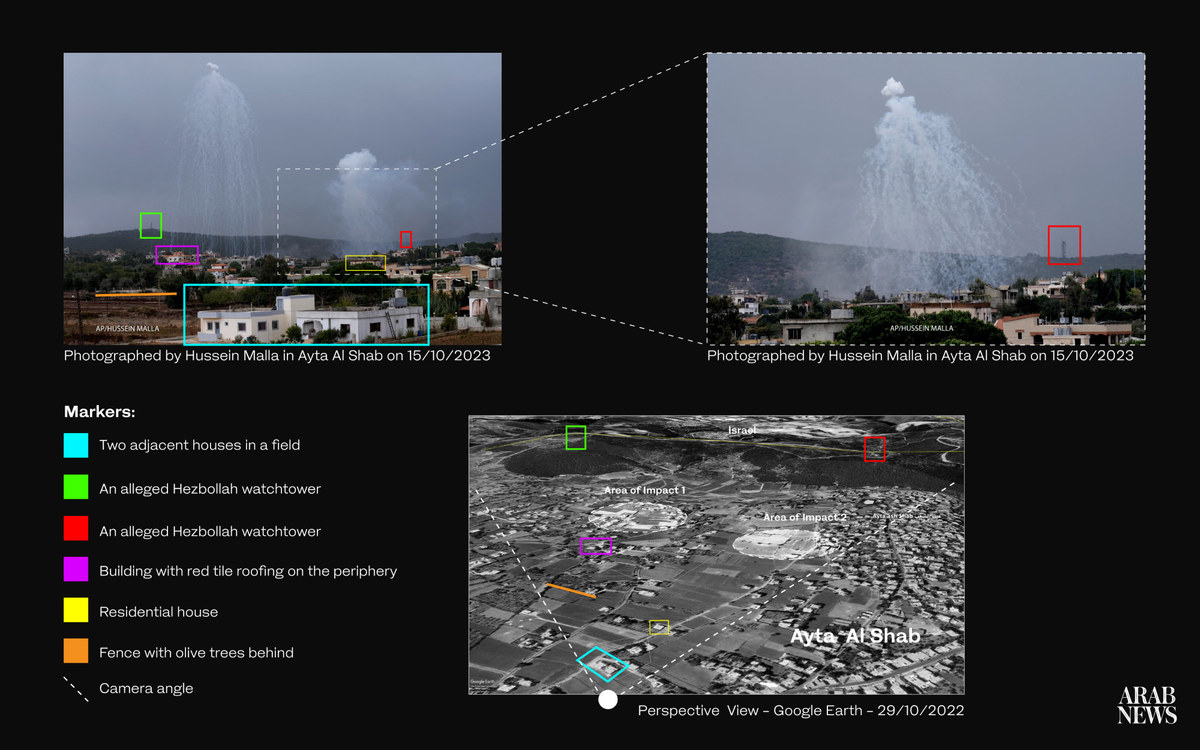

Geolocation Analysis: Pinpointing the exact locations of fires in Ayta Al Shab as depicted in the circulating video, utilizing landmark comparison with online images and satellite imagery for precise confirmation.

Lebanese lawmaker Saliba described the effect of the chemical agent on the human body. “White phosphorus is able to dissolve the skin, meaning that it will eat up the skin all the way to the bones and this is higher than third or fourth degree burning,” she told Arab News.

“You may not feel it the first day but the second day it will create this stomach ache and then vomiting and then you know that the phosphorus is inside your body, and there is very little you can do to save yourself from it.”

Saliba said that the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health has been making preparations to treat patients who may come into contact with white phosphorus, and has launched awareness campaigns for those living close to the border and other targeted areas.

Lebanese lawmaker and chemistry professor Najat Aoun Saliba. (AFP/file)

The Amnesty report detailed accounts of those treated at hospitals near the towns Dhayra, Yarine and Marwahin, where white phosphorus shelling has allegedly taken place.

“We were not able to see even our own hands due to the heavy white smoke that covered the town all night long and lasted till this morning (Oct. 17),” the regional director of the country’s civil defense told Amnesty.

Beyond the immediate harm caused by white phosphorus to human health and public infrastructure, the weapon can also have a long-term impact on the environment. This is having a devastating impact on the farming communities who have tilled Lebanon’s fertile hills for generations.

“Israel is purposefully tearing apart the ecosystem and destroying a land that’s been preserved for hundreds of years,” Hisham Younes, director of the Green Southerners, a civil society group that aims to preserve wildlife and cultural heritage in the south of Lebanon, told Arab News.

“What’s happening is the destruction of heritage and culture. The danger is great but the effects even greater.”

Israeli artillery shells, which appear to contain white phosphorus, explode over Dhayra, a Lebanese border village, on Oct. 16, wounding civilians, according to Amnesty International. (AP)

White phosphorus shells, right, have reportedly been used by the Israeli Defense Forces in Gaza and southern Lebanon, damaging farmland already scarred by the 2006 war. (Getty Images/AFP)

Southern Lebanon suffered massive ecological damage during the last large-scale confrontation between Israel and Hezbollah in 2006. More than one thousand hectares of forest and olive grove were destroyed by explosives and bushfires, according to a 2007 study by the Association for Forests, Development and Conservation.

It took four years to begin repairing the damage, with UNIFIL establishing an extensive reforestation project in the region in 2010. This time, however, the country may not be able to bounce back so easily.

“We have not recovered from the Beirut blast, and have not recovered from the 2006 war even,” said Saliba, referring to the Aug. 4, 2020 explosion at the Port of Beirut, which devastated a whole district of the Lebanese capital.

The disaster compounded the woes of a country already in the grips of its worst ever financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and a state of political paralysis, which has prevented lawmakers from establishing a new government.

Given Lebanon’s weakness, combined with Israel’s military superiority, Saliba believes only diplomacy can save the Lebanese people and their environment from disaster and destruction.

“I think Israel has used criminal or banned weapons everywhere. They’re not going to have mercy on us. So, if there is any way we can save the country from this devastation by doing all the diplomatic efforts, I think we should,” she said.

“It’s a historic moment and we should not spare any chance, any opportunity, to save the country from this war.”