DUBAI: Steeped in more than 5,000 years of history, Gaza has long been an archaeological treasure trove, with workers at construction sites regularly uncovering ancient gems.

Discoveries such as the monastery of Saint Hilarion, and Tel Umm el-Amr, arguably Gaza’s largest archaeological site, are perhaps unsurprising given Gaza’s proximity to holy places of Christianity, Islam and Judaism, three of the world’s biggest religions.

Gaza’s historical significance stems also from its location on ancient trade routes between Egypt and the Levant.

But with the past seven weeks of Israeli bombardment, there is growing concern over the future for both those sites uncovered and the ones yet to be discovered.

French archaeologists, Dominique M. Cabaret and Jean-Baptiste Humbert at the French Palestinian archaeological storage in Gaza City. (File photo by Fadel Al-Utol, 2021)

According to the Gaza-based Endowments and Religious Affairs Ministry, over 31 mosques have been destroyed and more than three churches severely damaged since fighting began in the wake of the deadly Oct. 7 raid by Hamas in southern Israel.

“Human life is more important than artifacts,” Jean-Michel de Tarragon, archivist for The Ecole Biblique in Jerusalem, a former professor of history at the Sorbonne and an archaeologist who excavated in Gaza from 1995-2005, told Arab News.

The pause since 2005 has been no coincidence. While the 1993 Oslo Peace Accords had made the work of archaeologists easier, de Tarragon said Hamas’ success in the 2006 Palestinian legislative election led to his team’s departure from the enclave.

(Hamas fighters took control of the Gaza Strip in 2007 from Fatah officials of the Palestinian National Authority, which led to the de-facto division of the Occupied Palestinian territories into two entities).

De Tarragon said the current war, which has seen the seashore “heavily bombed, seems to have completely destroyed the Greek Anthedon.”

Located on the Mediterranean coast in northwest Gaza, Anthedon was the region’s first sea port and had been inhabited from 800 BC to 1100AD, housing a variety of cultures from the Babylonian to the early Islamic period.

“From a historical point of view, during the period of late antiquity, Gaza was the sea port of the Nabataean trade network. It was the port of Petra, now Jordan, and also of AlUla, in Saudi Arabia, for ships heading in the direction of Rome and the Roman Empire,” he said.

Gaza-born and Dubai-based artist Hazem Harb, with artwork. (Supplied)

“As the secondary city of Gaza, Anthedon was very important. Another port, called Maioumas, existed in the south. But we did not dig there. We discovered Anthedon, then a beach camp, on the northern edge.”

Such is Anthedon’s rich history that UNESCO had placed it on a tentative list of Palestinian locations to qualify as a World Heritage site.

It is not alone, however, in facing an uncertain postwar fate, with de Tarragon pointing to a fifth-century Byzantine church, Mkheitim, as having been destroyed in the fighting although he noted that the mosaic floor appears to have survived.

“From now on, no archaeological work is envisioned in Gaza, only restoration work,” he said.

The fragility of life in war-prone Gaza and the intensity of the latest conflict have made it impossible to determine how many archaeological sites have been destroyed and the extent of the damage those still standing have suffered.

As to what it will take to bring them back to life remains a question for the future. For now, the sites serve a very different purpose: shelter from war.

Among them is one of the oldest working churches in the Palestinian enclave: Church of Saint Porphyrius.

Struck on the night of Oct. 20, it was reportedly sheltering at least 500 Christians and Muslims, with 16 killed, according to Palestinian officials.

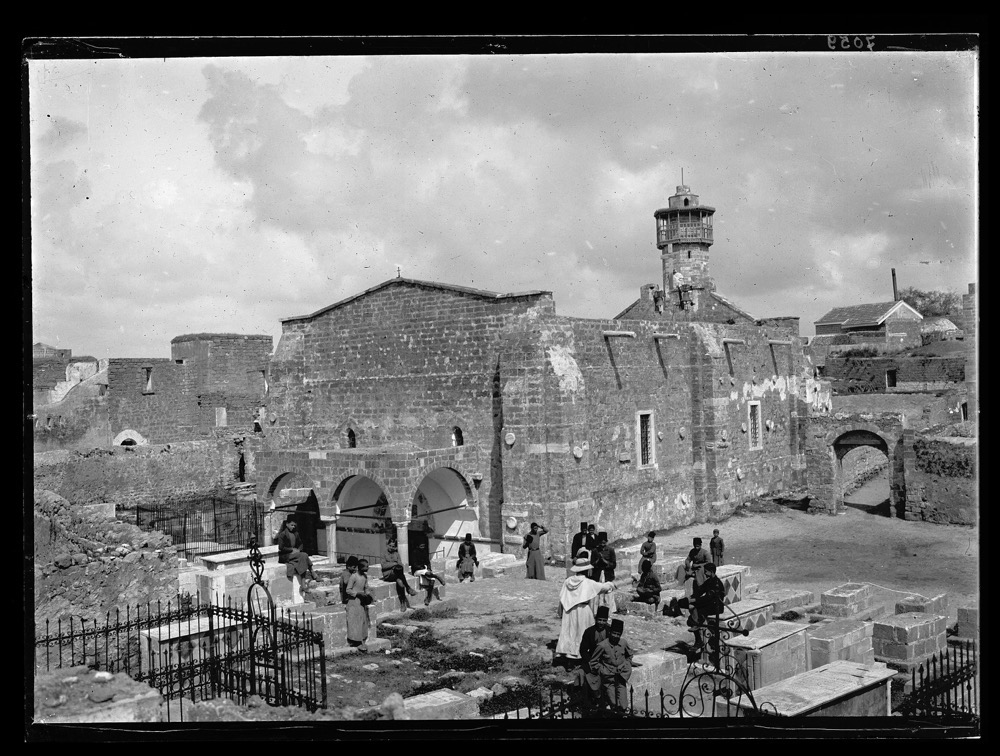

St. Porphyrius Greek Orthodox church in the Old City of Gaza in 1920. (Photo by Father Savignac, Ecole Biblique, Jerusalem.)

In a statement, the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem expressed “its strongest condemnation of the Israeli air strike that has struck its church compound in the city of Gaza.”

Witnesses told AFP news agency the strike damaged the facade of the church and caused an adjacent building to collapse.

“Targeting churches and their institutions, along with the shelter they provide to protect innocent citizens, especially children and women who have lost their homes due to Israeli airstrikes on residential areas over the past 13 days, constitutes a war crime that cannot be ignored,” the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem said.

Speaking to Arab News, Gaza-born and Dubai-based artist Hazem Harb said: “Artifacts are just as important as humans because they were made by us.”

His work has long focused on the incorporation of major sites from his Palestinian homeland.

Echoing a line he posted on the social-media site Instagram regarding the war, Harb said: “As I work with archive photography, all my work is supposed to pose history from a different perspective.

“Much of this photography has been denied from history and this is the same that is happening now with the destruction and legacy of these archaeological places.”

FASTFACTS

• In January this year, French archaeologists discovered 60 ancient graves at a Roman-era cemetery in northern Gaza.

• The findings, including two sarcophagi made of lead discovered in September, were made during construction of a housing project in Jabaliya.

• Given the rarity of the lead tombs, Palestinian archaeologists suspect social elites are buried at the cemetery.

In a statement on October 25, the International Council of Museums (ICOM) said: “ICOM expresses its deep concern about the current violence affecting Israeli and Palestinian civilians and deplores the significant humanitarian consequences that the conflict has had over the past weeks. ICOM extends its sincerest condolences to those who have lost family, friends, and community due to the violence.

“ICOM stands firm in its commitment to preserving cultural heritage and recalls the imperative of all parties to respect international law and conventions, including the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and its two protocols.”

It is well known that museums become sites of smuggling and looting amid the destruction and violence of war.

In October, ICOM warned about the potential increase in looting and the destruction of cultural monuments and objects, stressing the international legal obligations that work to prevent the illicit import, export, and transfer of cultural property, such as the 1970 UNESCO Convention and the 1995 Unidroit Convention.

Amid the violence and administrative collapse in Gaza, these obligations do not seem to have been adhered to.

Gaza is home to around 12 museums that contain approximately 12,000 artifacts. Many of these museums have been subjected to bombing and shelling during the ongoing war.

Museums that have allegedly been destroyed, include the Al-Qarara Cultural Museum near Khan Younis.

It was founded in 2016 and presented the archaeology and history of the area, which was collected and preserved by its founders and local community members.

The museum, which was granted a private license by the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, was designed to educate people about Palestinian cultural heritage and contained 3,500 archaeological and historical artifacts from Gaza, dating back to as far as 4,000 BC.

Another institution severely damaged is the Akkad Museum, which presented a permanent archive of archaeological pieces discovered in Palestine. It was established in 1975 and worked for many years, according to its website, in secret “because of the presence of the Israeli occupation.”

Akkad Museum includes about 2,800 artifacts from prehistoric to modern times.

Another important site has reported damage is the Pasha Palace Museum, which was built during the Mamluk era and became a museum in 2010.

Other crucial monuments based in Gaza include St. Hilarion Monastery, which de Tarragon says, citing his sources, has not been destroyed. The enclave’s largest known Christian monument, it is located in an area called Tel Umm Amer in central Gaza.

It is named after Hilarion, the founder of Palestinian monasticism in around 300 AD. There is also the Hammam Al-Sammara, or the Samaritan Bathhouse, located in Gaza City’s old Zaytoun quarter, a Turkish-style bath house named after the Samaritan community, an ancient offshoot of Judaism. Hammam Al-Sammara dates back to 1320 AD.

Gaza old city, around 1910, from the roof of the Latin Parish school. The Old Mosque is on the left. (Photo by Father Savignac, Ecole Biblique, Jerusalem)

De Tarragon pointed out that the archaeological community still does not know about the fate of many of these structures, so only time will tell.

Wars of the past have already destroyed much of Gaza’s once glistening heritage. They are now remembered by the photographs, the articles and the artworks that sustain their memory.

Even as violence continues to claim more and more civilian lives and remaining structures, Gaza’s contribution to world history, like the thousands of lives that have been lost, should not be forgotten.

As Harb said: “My thought is that there is no difference at all between the human being and our homes because our homes are not just stones.”