DUBAI: The renowned British explorer, travel writer, expedition leader and former soldier Sir Ranulph Fiennes has lived his life on the edge. He was the first to cross Antarctica on foot and reportedly the only person to set foot on both the North and South Poles.

Since he started his travels back in 1967, when he was in his early twenties, Fiennes has seen it all, including the great mountains Kilimanjaro, Everest and Elbrus, the latter being the highest mountain in Europe. So, where has this drive come from?

“It’s called DNA,” Fiennes tells Arab News. “My dad was killed in the Second World War, four months before I was born. My mum told me all about him. He’d been wounded so many times. He was in command of the greatest British tank regiment of the time and all I wanted to do, as I grew up, was to get into the British army and then become a colonel like dad. But I only reached the rank of captain.”

After exploring cold climates, Fiennes decided to head into “the great heat,” just like one of his heroes — the British archaeologist and intelligence officer T.E. Lawrence, famously known as Lawrence of Arabia — did.

An undated portrait of Sir Thomas Edward Lawrence, known as Lawrence of Arabia. (AFP)

Lawrence had a reputation for being a friend to the Arabs who were seeking autonomy from ruling Turks during the centuries-long Ottoman Empire. During World War One, he famously led bold military raids with Arab tribesmen in the great Arab Revolt. Like Lawrence, who died in 1935 at the age of 46, Fiennes was also involved in strategic military action in the Gulf, specifically Oman. In the late Sixties, he captained Arab troops in the Dhofar Rebellion, fighting against the Marxist threat.

“I saw an advertisement from the Sultan of Oman for a two-and-a-half year posting and I put my name in immediately and was accepted,” he recalls.

Ranulph Fiennes (front, center) with recce platoon in Dhofar 1968. (Supplied)

Fiennes has recently written a biography of Lawrence, in which he also offers his own perspective of battle. Lawrence’s story of the harsh heat of the desert has always resonated with Fiennes.

“When I went out (to Oman), I had a copy of one of Lawrence’s books with me and I really felt more about him than any other person that I’d read about,” he says.

Fiennes also explains in the book that “it was only after treading in his footsteps and embarking on similar adventures that I realized the man’s true greatness. . . While there are some interesting parallels between us, I’ve often found that he is a man without equal. His adventures in the desert were enough to stir the blood.”

Lawrence’s life of adventure began with a difficult childhood. He was reportedly abused by his mother. But his intelligence and maturity shone through from an early age.

“It was said that he could recite the alphabet by the age of three, while he could also read the newspaper upside down before he was five. He became fascinated by military history, devouring all manner of books on the subject, including all thirty-two volumes of Napoleon’s correspondence,” according to Fiennes.

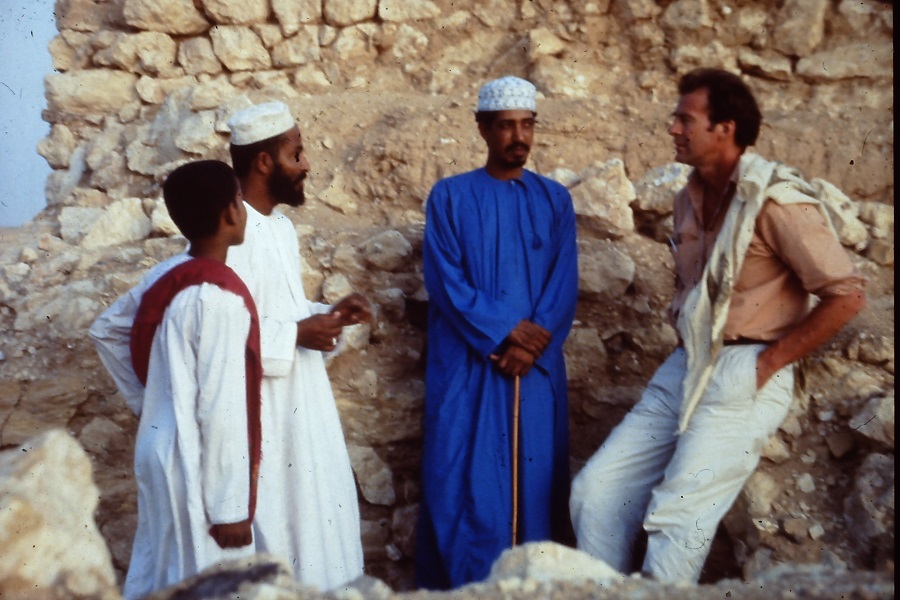

Ranulph Fiennes (right) in Oman in the late 1960s. (Supplied)

After studying history at Oxford University, Lawrence visited the Arab world for the first time in 1909, and it left a lasting impression on him. A few years later, he performed archaeological work in Carchemish in northern Syria.

Lawrence was fluent in Arabic, friendly and approachable, developing a bond with Arab communities, as well as offering them medical assistance. Fiennes says that the man fit right in.

“I came out with the definite opinion that he did love working with those particular Arabs and I loved working with the Arabs in a military situation, like he was. His actions made a great difference to the whole fight against the Ottoman Empire. He got on very well with the key guys, like Feisal. I don’t think you could have had a better person — Muslim or non-Muslim — than him in every way,” notes Fiennes.

The ‘Feisal’ that Fiennes is talking about is Prince Feisal Bin Al-Hussein, the son of the Grand Sharif of Makkah. The prince was the leader of the revolt, and a close ally of Lawrence.

“I felt at first glance that this was the man I had come to Arabia to seek, the leader who would bring the Arab Revolt to full glory,” Lawrence once wrote of the prince in his memoir, “Seven Pillars of Wisdom.”

Between 1916 and 1918, the revolt galvanized Lawrence and Arab troops to attack Turkish-heavy locations in modern-day Syria and Jordan, notably the Hejaz Railway and the Aqaba fort. There was a lot of marching in the desert for miles on end, an intense task which tested Lawrence.

“He was a very hardy guy,” says Fiennes. “He could put up with discomfort an awful lot. On one occasion, when he was leading an attack, he shot his own camel as he charged and fell off. He managed to just get back on again and carry on. That was just one of many examples of his hardiness. It’s not normal to start camel travel with a gun. You normally do it slowly and learn to get comfortable on board a camel.”

Aside from setting foot in Damascus and Aleppo, Lawrence also stayed in modern-day Saudi Arabia. His traditional two-story house in the city of Yanbu, located on the Red Sea, still stands today. It was recently renovated to attract visitors and history enthusiasts.

Victory for the Arab Revolt turned sour when the winners of the First World War — Britain and France, among other nations — unveiled their own plans for controlling the Levant, going against Lawrence’s promise that the Arabs would have the right to self-rule.

“He felt terribly guilty that the Brits would take over, like the French and sometimes the Russians, instead of handing it straight over,” says Fiennes. “Unfortunately, he was not in as important a position as those people who wanted the French and Brits to divide Arabia between them.”

When the disappointed Lawrence returned to England, he kept a low profile. “He was very honest about his own view of himself. He didn’t want to be famous or infamous. He just wanted to disappear,” says Fiennes.

Nearly five decades have passed since Fiennes’ days in Oman, but despite the fact that he and his men were in a situation where life could be snatched away at any moment, he has many fond memories.

“I am very lucky to have had such a wonderful time with many Arab soldiers in Oman,” he says. “Many things that were in Lawrence’s book remind me of the happy times — all the nights sitting around the fire, joking and laughing — with those soldiers in the desert.”