LONDON: Faced with a multitude of economic, safety and regulatory challenges in neighboring countries, hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees who fled the civil war have returned home, despite the grim security and humanitarian situation that awaits them.

For many, this decision has exacted a heavy toll. A recent report by the UN Human Rights Office found that many refugees who fled the conflict to neighboring countries over the past decade now “face gross human rights violations and abuses upon their return to Syria.”

The report, published on Feb. 13, documented incidents in various parts of the country perpetrated by de facto authorities, the Syrian government, and an assortment of armed groups.

“The situation in these host countries has become so horrible that people are still making the decision to return back to Syria in spite of all the challenges,” Karam Shaar told Arab News. (AFP/File)

Returnees have to run the gauntlet of perils at the hands of “all parties to the conflict,” including enforced disappearance, arbitrary arrest, torture and ill-treatment in detention, and death in custody, the report said.

Many of the returnees interviewed by the UN Human Rights Office said that they were called in for questioning by Syrian security agencies after their return to Syria.

Others reported being arrested and detained by government authorities in regime-held areas, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham or Turkish-affiliated armed groups in the northwest, and the Syrian Democratic Forces in the northeast.

Not everyone who has returned to Syria has done so voluntarily.

On Sunday, reports emerged on social media of four Syrian detainees in Lebanon’s Roumieh prison near Beirut threatening to commit suicide after a brother and fellow inmate of one of the men was handed over to Syrian government authorities on March 2.

According to Samer Al-Deyaei, CEO and co-founder of the Free Syrian Lawyers Association, who posted images of the prison protest on social media, the men are receiving medical attention and have been given assurances that their files would be reviewed.

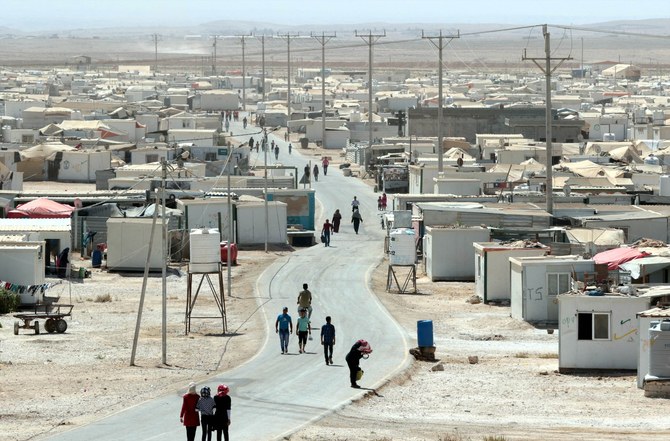

Since violence erupted in Syria, more than 14 million people have fled their homes. (AFP/File)

However, the dispute has highlighted the willingness of Lebanese authorities to place Syrian refugees into the custody of regime officials, despite well documented cases of abuse in Syrian jails, thereby putting Lebanon in breach of the principle of non-refoulement.

Non-refoulement is a fundamental principle of international law that forbids a country receiving asylum seekers from returning them to a country in which they would be in probable danger of persecution.

But fear of persecution has not stopped many thousands of Syrians who had been sheltering abroad from returning home in recent years.

Since 2016, the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, has verified or monitored the return of at least 388,679 Syrians from neighboring countries to Syria as of Nov. 30, 2023.

Karam Shaar, a senior fellow at the Newlines Institute for Strategy and Policy, a nonpartisan Washington think tank, believes the bleak situation in host countries such as Lebanon and Turkiye was the primary reason for the voluntary return of many Syrian refugees.

“The situation in these host countries has become so horrible that people are still making the decision to return back to Syria in spite of all the challenges,” he told Arab News.

“So, basically, they are between a rock and a hard place. And the sad thing is that no one is really even listening to them.”

Since 2016, the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, has verified or monitored the return of at least 388,679 Syrians from neighboring countries to Syria as of Nov. 30, 2023. (AFP/File)

Although Syrians enjoyed more international sympathy early in the civil war, which began in 2011, and when Daesh extremists were conquering swathes of the country in 2014, it has since become a “protracted conflict that not many governments are actually interested in looking at,” Shaar said.

Since violence erupted in Syria, more than 14 million people have fled their homes, according to UN figures. Of these, some 5.5 million have sought safety in Turkiye, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon and Egypt, while more than 6.8 million remain internally displaced.

Syrians in these host countries have also experienced hostility and discrimination at the hands of local communities. This hostile environment has been made worse by a rise in anti-refugee rhetoric.

“Politicians in neighboring countries always capitalize on these refugees and try to leverage their presence politically and even economically, such as in Jordan and in Egypt,” Shaar said.

In the study of migration, there are several “push and pull factors” that contribute to a person’s “decision to migrate or stay,” he said.

In the case of Lebanon, for instance, “the pull factors from Syria are virtually non-existent,” because a returnee might be persecuted, basic services are on the brink of collapse, there is widespread unemployment and inflation is high.

“However, on balance, that decision still makes sense only because the push factors are even harder,” Shaar said.

“So, these push factors in Lebanon, for example, include the inability to seek a job, the fact that the Lebanese government is now harassing UNHCR and asking them not to register refugees, the difficulties related to educating your children in public schools, and so on.”

For Syrian refugees, “the situation in Turkiye is also turning extremely dire,” he said.

Many of the returnees interviewed by the UN Human Rights Office said that they were called in for questioning by Syrian security agencies after their return to Syria. (AFP/File)

The refugee issue took center stage during the Turkish presidential election in May last year, with several opposition candidates campaigning on pledges to deport refugees.

Despite the country hosting an estimated 3.6 million registered Syrian refugees, Syrians have not been offered a seat in Turkiye’s political debates about their fate.

Similarly, in Lebanon, Syrian refugees live with the constant fear of deportation, especially after the Lebanese Armed Forces summarily deported thousands of Syrians in April 2023, including many unaccompanied minors.

The move was condemned by human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and the Human Rights Watch.

WHO HOSTS SYRIAN REFUGEES?

• 3.6m Turkiye

• 1.5m Lebanon

• 651k Jordan

• 270k Iraq

• 155k Egypt

Source: UNHCR

However, Jasmin Lilian Diab, director of the Institute for Migration Studies at the Lebanese American University, believes the lack of economic opportunities in neighboring countries has been the key issue that has driven Syrians to return or migrate elsewhere.

Some 90 percent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon live in extreme poverty, 20 percent of whom exist in deplorable conditions, according to the European Commission, citing data from UNHCR.

Due to the country’s economic collapse, coupled with insufficient humanitarian funding and the government’s rejection of local integration or settlement of refugees, these Syrians find themselves ever more vulnerable.

Syrian refugees interviewed by Diab’s team said that they would return because they are “tired of waiting around in the host country for a few things.”

Claiming that “everybody in Lebanon who is Syrian can return” is “not a safe narrative (or) a safe message to propagate,” said Jasmin Lilian Diab. (AFP/File)

Emphasizing that this was “not the overwhelming majority,” Diab said “many people returned from Lebanon because, after 12 years, there are really no integration prospects.”

She said: “The overwhelming majority of (Syrian refugees) would not prefer to stay or return but would rather engage in onward migration.”

Describing the current situation for most Syrian refugees in Lebanon as a “legal limbo,” Diab said “there is currently no willingness to integrate this population.”

Local municipalities across Lebanon have also imposed measures against Syrians that Amnesty International described as “discriminatory.” These include curfews and restrictions on renting accommodation.

Syrians in Lebanon rely on the informal labor market and humanitarian aid to survive. This population is mainly employed in agriculture, sanitation, services and construction.

Due to the limited resources and a lack of integration prospects, Diab believes that for many refugees, returning to Syria “makes sense.”

Fear of persecution has not stopped many thousands of Syrians who had been sheltering abroad from returning home in recent years. (AFP/File)

She said: “Even though there are reports on persecution and detainment, people who have returned have done that through their own family networks. The majority of people we have spoken to are not returning in a vacuum or venturing out on their own.

“They are doing this based on the recommendation of a family member who has either been there the entire conflict and tells them now it is safe enough to return or that they have secured a job or a livelihood opportunity for them.”

Diab said that another strategy employed by returnees is to go to Syria “in waves,” meaning that the primary breadwinner, predominantly a male figure, would return alone initially to “check the situation.” The rest of the household stays put, “waiting for his green light” to join him.

And while several host governments have discussed developing plans for the repatriation of Syrian refugees to Syria, UNHCR said last year the country was not suitable for a safe and dignified return.

Calling for a political resolution to the Syrian conflict, King Abdullah of Jordan stated in September 2023 at the UN General Assembly that his country’s “capacity to deliver necessary services to refugees has surpassed its limits.”

He noted that “refugees are far from returning” and that the UN agencies supporting them have faced shortfalls in funds, forcing them to reduce or cut aid.

The Lebanese government in 2022 announced a plan to repatriate 15,000 Syrian refugees to Syria per month under the pretext that “the war is over,” therefore “the country has become safe.”

But Diab does not believe the Lebanese government has “any assessments as to what safety means.”

Not everyone who has returned to Syria has done so voluntarily. (AFP/File)

“I do not think at the moment there are enough efforts to facilitate a safe return,” she said, highlighting that the Lebanese government “homogenizes the Syrian refugee population” and does not assess individuals’ situations to determine who might be able to return and for whom Syria was never safe.

“Now, because we lump all Syrians together in Lebanon, conversations on safety are very tricky to have,” Diab said.

Claiming that “everybody in Lebanon who is Syrian can return” is “not a safe narrative (or) a safe message to propagate,” she said.