ABIDJAN Cote d’Ivoire: Already plagued by complex internal problems, the economies of East Africa have perhaps been the most affected among regional states by the unfolding crisis in Sudan and the attacks on trade passing through the Red Sea.

The conflict in Sudan between the Sudanese Armed Forces, or SAF, and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, or RSF, which began on April 15 last year, has caused massive internal and cross-border displacement as well as disruption of critical supply chains.

Meanwhile, attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea by Yemen’s Houthi militia, launched in response to Israel’s military operation in Gaza, have interrupted trade traffic plying East Africa’s ports, as wary firms redirect their vessels.

As a result, ports in Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somaliland have seen a reduction in the number of vessels docked.

Houthi and Palestinian flags are raised on the Galaxy Leader, a Bahamas-flagged, British-owned cargo ship seized by the Iran-backed Huthi militia off Yemen on last November. The ship is docked in a port on the Red Sea in the Yemeni province of Hodeida. (AFP/File)

The combination of these crises has hampered exports and cut revenues at a time when many regional states are themselves emerging from years of conflict, sluggish development and poor governance, all while coping with mounting climate pressures.

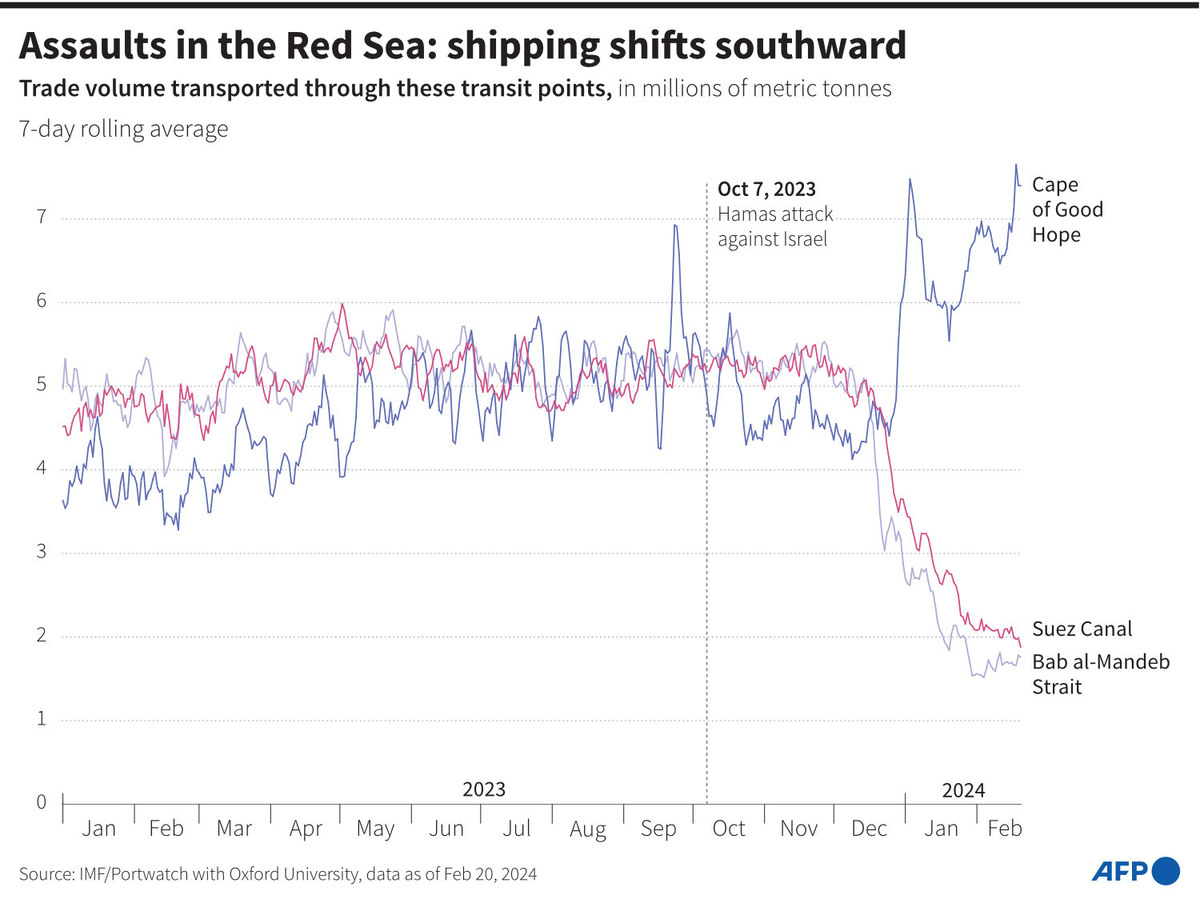

Egypt, for one, has suffered a significant financial blow owing to its reliance on revenues from ships passing through the Suez Canal, which has been hit by the diversion of vessels since the Houthi attacks began.

In the 2022-23 fiscal year, the Suez Canal brought Egypt $9.4 billion in revenues, according to Reuters news agency. In the first 11 days of 2024, these revenues fell by 40 percent compared with the same period in the previous year.

Egyptian authorities said that revenue in January from the Suez Canal had fallen 50 percent since the start of the year, compared with the same period in 2023. According to Reuters, instead of the 777 ships that navigated the canal last year, only 544 made the journey in early 2024.

The combination of shipping attacks and the war in Gaza has also resulted in a plunge in tourist arrivals. According to S&P Global Ratings, Egypt’s tourism revenues are set to experience a 10-30 percent fall from last year.

However, it is the world’s youngest nation, South Sudan, that has proven especially vulnerable to the recent regional instability.

Since the conflict in Sudan began, neighboring South Sudan has accepted hundreds of thousands of Sudanese refugees escaping violence, ethnic cleansing and economic collapse, which have brought the country to the brink of famine.

South Sudan has also absorbed tens of thousands of its own citizens who had been living in Sudan. The sudden arrival of so many people has put a strain on South Sudan’s infrastructure and on the budgets of aid agencies already operating in the country.

INNUMBERS

• 50+ Vessels using Bab Al-Mandab Strait targeted by Houthis so far.

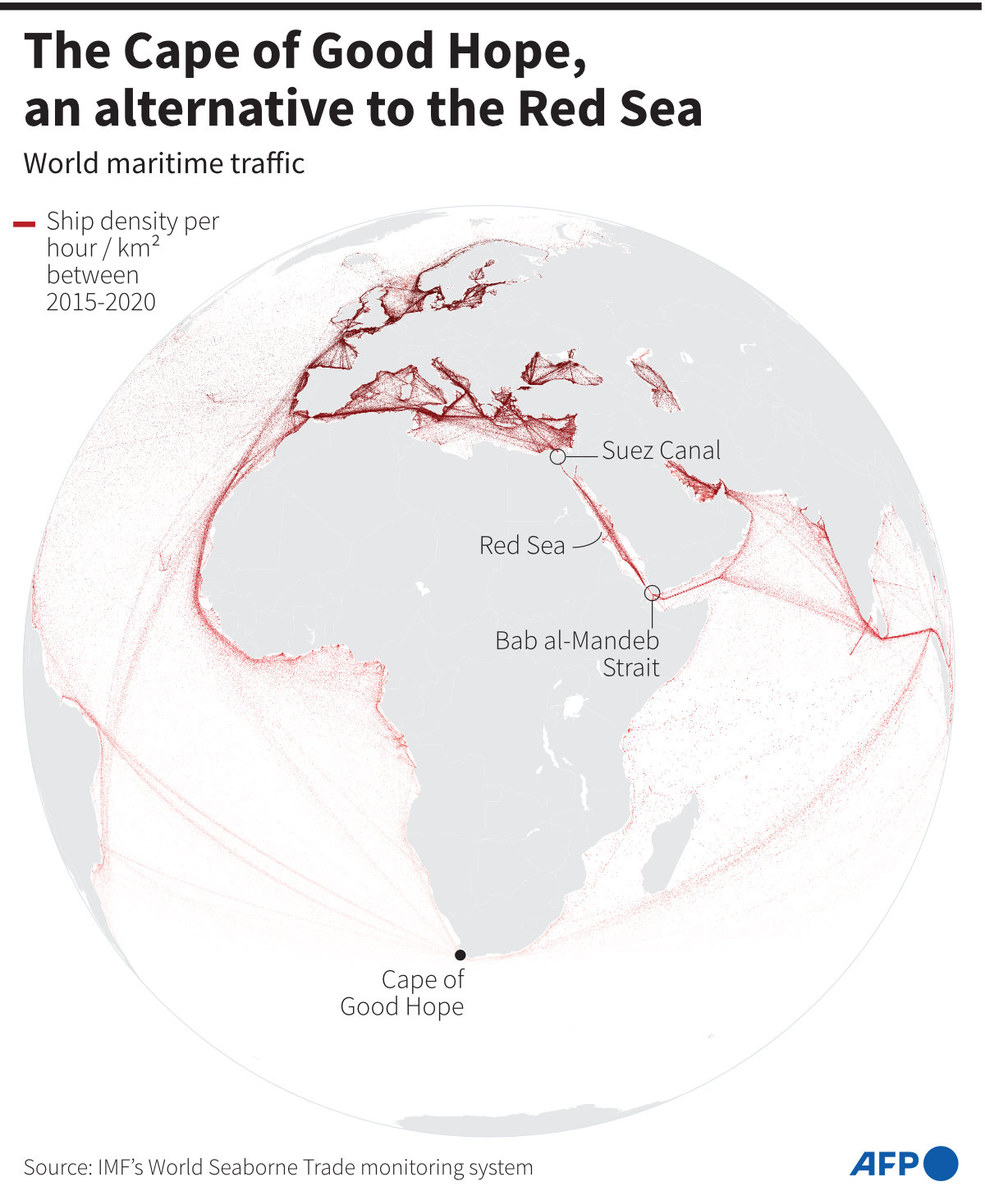

• 3,500 nautical miles Additional distance for Cape of Good Hope route.

• 14 Extra days for a Rotterdam-Singapore journey bypassing Suez Canal.

The crisis in Sudan has also led to a proliferation of arms across porous national borders, coupled with the recruitment of foreign fighters from across the troubled Sahel belt, and the establishment of new training camps in Eritrea, threatening the wider region.

“It’s a disaster,” Dalia Abdelmoniem, a Sudanese political analyst, told Arab News. “The continuing infiltration of weapons is only worsening the war. The fact that weapons are flowing while humanitarian aid does not always get through says it all, really.”

The challenges do not end there, however. Pipelines carrying South Sudanese oil through territories on Sudan’s side of the border have fallen under the control of the RSF, forcing Juba to negotiate deals with the paramilitary group.

In fact, the UN believes the RSF has established a fuel supply line through South Sudan to power its war effort — allegations that Juba denies.

Pipelines carrying South Sudanese oil through territories on Sudan’s side of the border have fallen under the control of the RSF, forcing Juba to negotiate deals with the paramilitary group. (AFP/File)

The oil that passes through these pipelines is shipped from Port Sudan on Sudan’s Red Sea coast. As such, South Sudan’s entire oil export process relies on Sudanese infrastructure, leaving its economy extremely vulnerable to any instability in Sudan and on the Red Sea.

At the onset of Sudan’s conflict, shipping firms refused to dock at Port Sudan unless they were given a discount. Matters were then made worse when Yemen’s Houthis began attacking vessels passing through the region, causing many ships to steer clear.

Exports from Sudan’s Bashayer Oil Terminal Port reportedly hit an 11-month low of 79,000 barrels a day in February. Juba has been searching for alternative avenues through which to export its oil. To date, however, nothing has materialized.

“South Sudan is currently facing a severe economic crisis due to the mismanagement of resources, corruption, and a failure to diversify its economy,” Akol Miyen Kuol, a South Sudanese analyst, told Arab News.

The oil industry constitutes some 90 percent of South Sudan’s revenue and nearly all of its exports, according to the World Bank.

A view of an oil refinery complex in South Sudan. Oil constitutes almost all of South Sudan’s revenue and nearly all of its exports, according to the World Bank. (Courtesy of South Sudan Ministry of Petroleum)

In addition to its dependence on the infrastructure of its northern neighbor, “the lack of economic diversification over the past 13 years impacts citizens significantly,” Kuol said.

The disruption to supply chains and economic activity in South Sudan has hit imports, resulting in currency depreciation and a 30 percent increase in the price of bread.

“South Sudan is not just engulfed in rising inflation, it is an impending humanitarian crisis and abject poverty all around is at an unprecedented level,” Suzanne Jambo, a South Sudanese politician and lawyer, told Arab News.

According to the World Bank, an estimated 9.4 million people, constituting roughly 76 percent of the country’s population, required humanitarian assistance in 2023. If disruption to trade continues, this number could grow.

Indeed, South Sudan’s economic woes are creating fresh political instability and security risks.

A South Sudanese soldier monitors the area as troops belonging to the South Sudanese Unified Forces take part in a deployment ceremony at the Luri Military Training Centre in Juba on November 15, 2023. Hundreds of former rebels and government troops in South Sudan's Unified Forces were deployed at a long-overdue ceremony on November 15, 2023, marking progress for the country's lumbering peace process. (AFP)

The recent US arrest of Peter Biar Ajak, a South Sudanese opposition leader living in exile, for alleged arms smuggling, highlights the desperation among some of the country’s elites, who appear intent on plunging the country into a renewed bout of civil war.

And there appears to be little sign of relief for South Sudan’s economy on the horizon.

Not only are the warring parties in Sudan reluctant to agree to a ceasefire — many region watchers think Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping will continue even after the conflict in Gaza ends.

Analysts believe the volatile security situation in the Red Sea has led to a militarization of the wider region.

“The ongoing instability in the Red Sea region benefits stakeholders seeking to expand control and influence at the expense of political stability and security,” said Sudanese political analyst Abdelmoniem.

When the Houthis began attacking commercial shipping in November, they claimed they were only targeting vessels with links to Israel in an attempt to pressure the Israeli government to end its military operation against Hamas in Gaza.

The UK-owned Rubymar hit by Houthi missiles in February causing an oil slick in the Red Sea. (AFP)

“These attacks not only pose a security threat but also serve as an effective public relations campaign,” Frank Slijper, an arms trade expert at PAX, a Dutch peace organization, told Arab News.

“This signals their likely persistence unless Israel ceases its military actions against Gaza.”

However, Houthi drones, missiles and acts of piracy have been launched against multiple ships with no ties to Israel, indicating the threat to shipping is viewed by the Houthi leadership as a potential source of revenue and strategic advantage.

In response to these attacks, many of the world’s biggest freight companies have redirected their vessels from the Suez Canal route to the Mediterranean, thereby avoiding the Red Sea, and instead are using much longer and more expensive routes via the Cape of Good Hope.

To prevent disruption to trade, protect mariners and uphold the right to freedom of navigation, the US-led patrol mission, Operation Prosperity Guardian, was established in December.

When the Houthi attacks persisted, the US and UK launched strikes against militia targets in Yemen. However, the adaptive and well-equipped Houthi militia, with nine years of combat experience in Yemen, persists in its attacks using drones and missiles supplied by Iran.

Kholood Khair, a founding director of Confluence Advisory, a Khartoum-based think-tank, told Arab News: “These developments underscore that the Red Sea has evolved into an arena of international competition and conflict.”

Khair said that each country in the region operates based on its own logic but is also susceptible to influence from other Red Sea states and global powers such as Russia, the US and China.

Supporters and members of the Sudanese armed popular resistance, which backs the army, meeting with the city's governor in Gedaref, Sudan, on January 16, 2024 amid the ongoing conflict in Sudan between the army and paramilitaries. (AFP)

She said this is exemplified by Iran’s shipment of weapons to support the SAF at a time when SAF commander and de facto president General Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan is engaged in talks with Israel about opening Sudan’s airspace to Israeli planes.

Khair said the situation “illuminates the strategic maneuvering and exploitation of diverse interests among conflicting parties” in the Red Sea region.

“What would make most sense is that the Red Sea countries should get together and set up some kind of mutual working relationship related to the Red Sea,” she told Arab News. “That way it doesn’t become an area of conflict but an area of cooperation.”

Although there have long been talks about establishing such a grouping to manage the common interests of the Red Sea littoral states, progress has been slow, in part owing to the imbalance in the size of regional economies and to the presence of US, Russian, Chinese and European naval bases in the region.

However, until regional conflicts are resolved and international shipping is permitted to traverse the Red Sea unmolested, the economic drag on regional economies is liable to continue, with potential security implications across East Africa and beyond.