METTUR, India: Despite failing 238 times in his bid for public office in India, K. Padmarajan is unperturbed as he prepares, yet again, to contest elections in the world’s largest democracy.

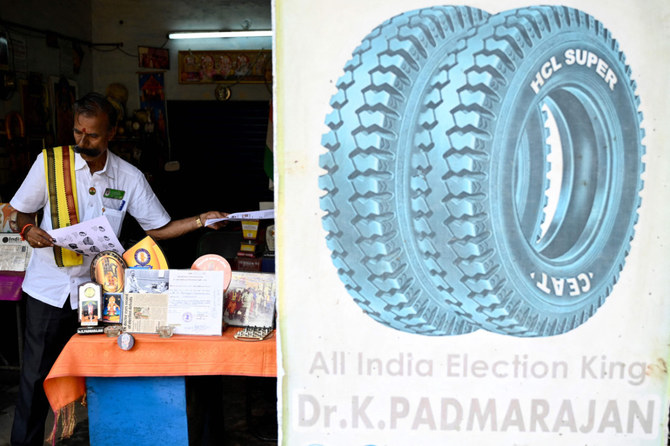

The 65-year-old tire repair shop owner began fighting elections in 1988 from his hometown of Mettur in the southern state of Tamil Nadu.

People laughed when he threw his hat into the ring, but he said he wanted to prove that an ordinary man can take part.

“All candidates seek victory in elections,” said Padmarajan, sporting a bright shawl draped over his shoulder and an imposing walrus moustache. “Not me.”

For him, the victory is in participating, and when his defeat inevitably comes, he is “happy losing,” he said.

This year, in India’s six-week-long general elections that begin on April 19, he is contesting a parliamentary seat in Tamil Nadu’s Dharmapuri district.

Popularly dubbed the “Election King,” Padmarajan has competed across the country in elections ranging from presidential to local polls.

Over the years he has lost to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, former premiers Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh, and Congress party scion Rahul Gandhi.

‘It is about involvement’

“Victory is secondary,” he said. “Who is the opposite candidate? I do not care.”

Padmarajan’s main preoccupation now is extending his losing streak.

It has not come cheap — he estimates he has spent thousands of dollars in more than three decades of nomination fees.

That includes a security deposit of 25,000 rupees ($300) for his latest tilt, which will not be refunded unless he wins more than 16 percent of the vote.

His one victory has been to earn a place as India’s most unsuccessful candidate in the Limca Book of Records, the country’s archive of records held by Indians.

Padmarajan’s best performance was in 2011, when he stood for the assembly elections in Mettur. He won 6,273 votes — compared to more than 75,000 for the eventual victor.

“I did not even expect one vote,” he said. “But it showed that people are accepting me.”

In addition to his tire repair shop, Padmarajan provides homoeopathic remedies and works as an editor for local media.

But among all his jobs, fighting elections was the most important, he said.

“It is about involvement,” he said. “People hesitate to put in their nominations. So I want to be a role model, to create awareness.”

‘Failure is best’

Padmarajan maintains detailed records of the nomination papers and identity cards from each of his failed bids for statesmanship, all laminated for safekeeping.

Each bears the multitude of campaign symbols he has used; a fish, ring, hat, telephone and, this time, tires.

Once the subject of ridicule, Padmarajan is now asked to address students about resilience, using his campaigns to explain how to bounce back from defeat.

“I do not think of winning — failure is best,” he said. “If we are in that frame of mind, we do not get stressed.”

Padmarajan’s lesson in democracy comes at a time when public support for India’s clamorous democratic process appears to be waning.

A February survey by the Pew Research Center found 67 percent of Indians thought that a strong leader unencumbered by parliament or the courts was a better system of government than representative democracy — up from 55 percent in 2017.

Rights groups also say that democracy has become increasingly illiberal under Modi, with several criminal probes into opposition party leaders making this year’s election appear increasingly one-sided.

Padmarajan said it was important, now more than ever, that every citizen of the country exercise their franchise.

“It is their right, they should cast their votes, in that respect there is no winning or losing,” he said.

Padmarajan said he will continue to fight elections until his last breath — but would be shocked were he ever to win.

“I will have a heart attack,” he laughed.