DUBAI: With budgets squeezed by rising prices and limited donations, humanitarian agencies are struggling to respond to the world’s multiple, overlapping crises, contributing to a rise in malnutrition, a top aid official has warned.

Corinne Fleischer, the World Food Programme’s regional director for the Middle East, North Africa and Eastern Europe, said that her agency had been forced to reduce its assistance to communities in several crisis contexts.

“This is due to conflicts, the impact of COVID-19, and the impact the Ukraine war has on food prices,” Fleischer told Arab News in an interview in Dubai. “Hunger is going up and governments are now looking at their own economies and needs.

“The humanitarian system is really challenged. It is a dramatic situation.”

Corinne Fleischer, the WFP’s regional director for the Middle East, North Africa and Eastern Europe, said the Saudi aid agency KSrelief had recently agreed to provide $5 million for the WFP's relief operations in Palestinian territories. (Getty Images)

Fleischer, who recently held a meeting in Egypt with Dr. Abdullah Al-Rabeeah, supervisor-general of the King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center (KSrelief), said that WFP was very pleased to have strengthened its relationship with the Saudi aid agency.

“We signed an agreement where KSrelief will provide $10 million for our operations in Ukraine, $5 million for Palestine, $4.85 million to Yemen, and $1.4 million for Sudan and South Sudan,” she said.

“The focus of these contributions is of course saving lives and providing nutrition with a focus on mothers, pregnant and nursing mothers and young children under two.”

This additional financial assistance could prove lifesaving for the population of Gaza, which has endured months under Israeli siege.

More than six months after Israel launched its military offensive and placed tight restrictions on the flow of commercial goods and humanitarian aid permitted to enter the Palestinian enclave, the population has been brought to the brink of famine.

“I have never seen, even the world has never seen, such a rapid increase in hunger, where now 50 percent of the population is starving,” Fleischer said.

According to WFP figures, 0.8 percent of Gazan children were categorized as malnourished prior to the war. Just three months into the conflict, that number rose to 15 percent. A further two months later, it rose to 30 percent.

“From the beginning, we knew where the conflict might go, so we made sure we have enough food at the borders for 2.2 million people to be able to move in as soon as we can,” Fleischer said.

INNUMBERS

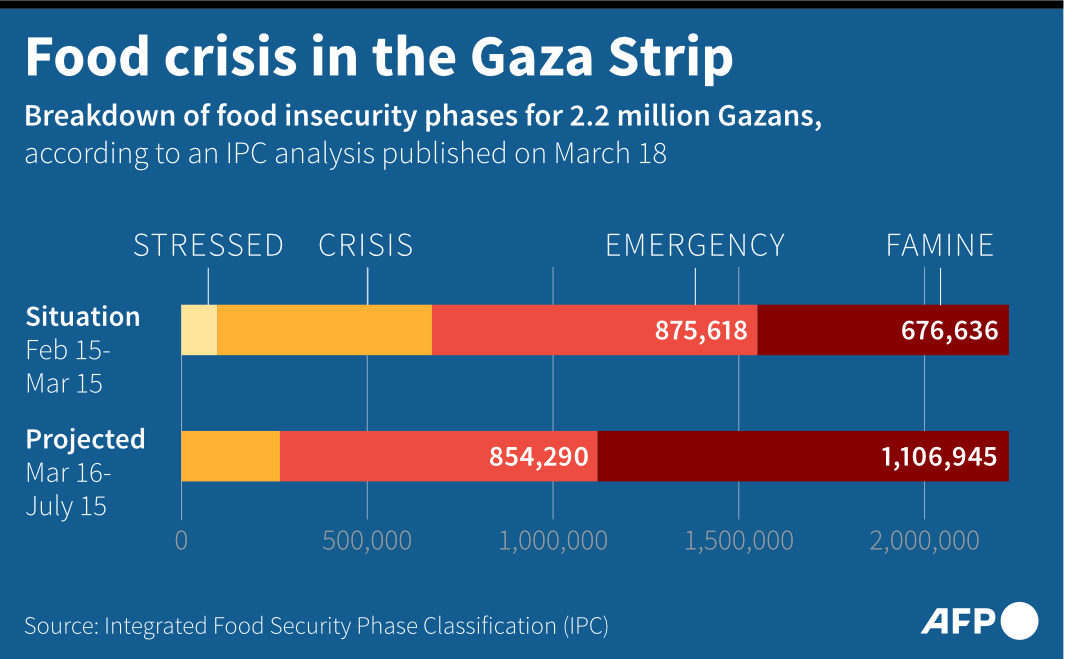

• 1.1 million Gazans experiencing catastrophic hunger — a number that has doubled in just 3 months.

• 1/3 Sudanese — 18 million people — facing acute or emergency food insecurity 1 year into the conflict.

• 900,000 Syrian refugees in Lebanon that WFP provided with food and other basic needs in February alone.

Although WFP continues to bring aid deliveries into Gaza, the number of trucks allowed in is far too limited to meet the needs of the stricken population. Some 500 trucks were entering the enclave prior to the war. Now barely 100 are permitted to enter — at a time when needs are at their greatest.

“We use the Rafah corridor, the Jordan corridor, which we’ve also set up, but the aid from there goes through Kerem Shalom and this is where the choke point is,” Fleischer said.

Kerem Shalom, which used to be the main commercial crossing between Israel and Gaza, has been repeatedly blocked by Israeli protesters demanding the release of hostages.

WFP has called on Israel to open more crossing points and is now able to go through the Erez Crossing. According to Fleischer, this has allowed aid agencies to access communities in the north of Gaza, where famine is taking hold.

“We managed in the last month to bring food for about 350,000 people,” she said. “That is not enough for a whole month, but it’s a start.”

Fleischer said that it was a good sign that they were now able to use other road routes within Gaza to distribute aid, such as the Salah Al-Din Road, the main highway of the Gaza Strip, where WFP now sends regular convoys, and the Port of Ashdod, one of Israel’s three main cargo ports.

Palestinians line up for a meal in Rafah, Gaza Strip, on Feb. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/File)

“We are now able to send wheat, flour and other foods, and that is hugely important,” Fleischer said. “Ashdod is a functioning port. It will be able to get us directly into Gaza and into its north.

“While the signs are good now that more openings are being provided, it needs to be sustained. We still have famine on our watch from the six months of not being able to send in any aid, and let me tell you what that means besides giving statistical numbers.

“When we come with our trucks, people jump on them. Not only that, they open the boxes, they take the food and eat it first before they take the rest to their families. Can you imagine how hungry they are?

“That is disastrous and so we need to be able to bring this down, to give confidence to people that food is coming on a daily basis so they also are not attacking our trucks. We need this to be sustained at a much larger scale. There are 2.2 million people in Gaza that need food.”

Fleischer said that private businesses such as bakeries must also be restored and reopened, as humanitarian agencies alone will not be able to sustain Gaza for the entirety of the conflict should it continue. WFP assistance has helped 16 to reopen.

“We are now restoring bakeries,” she said. “In the north, people haven’t eaten bread for a long time, and because we are able to go there currently, we are bringing fuel to bakeries as well as wheat, flour, yeast and sugar. So they’ve started operating again.

Shuttered bakeries in Gaza are gradually being restored with the help of the Un World Food Programme. (Supplied)

“We also have contacts with retail shops that we used before the war. Now we are working with them, we bring them our food and the parcels that we provide, and they distribute it, so they stay alive, they keep their workers, they open every day. So as soon as commercial food comes in again, they are ready.”

WFP has been touted as a potential replacement for the UN Relief and Works Agency as the primary aid agency working in Gaza after Israel raised allegations in January suggesting UNRWA staff had participated in the Hamas-led attack of Oct. 7, leading several donor nations to suspend funding pending an investigation.

“We cannot replace UNRWA. That is very clear,” Fleischer said. “UNRWA does much more than bring food to people. We are distributing food in camps that are managed by UNRWA. It needs to stay. That is very clear.”

Israeli soldiers operate next to the UNRWA headquarters in the Gaza Strip on February 8, 2024. (Reuters)

Gaza is not the only hunger hotspot in the region, nor the only one that has seen the provision of aid by WFP dwindle owing to funding constraints — the worst the agency has experienced in 60 years.

These budget cuts have raised concerns among refugee host countries such as Jordan and Lebanon about the continuation of assistance. “This can really impact stability and what it means for the region,” Fleischer said.

“Syria is no longer at the top of the list now. Two years ago it was. But then came the Ukraine war and now we have Gaza. Do you know how this translates in terms of the assistance we provide to Syrians? We are the safety net for them. They don’t get much subsidies.

“We went from supporting six million people every month with food to three, to now one million within seven months because of lack of funding. The situation is desperate. And now you also see malnutrition rates going up there.

“I can tell you in Syria, when we announced those cuts, we had weapons at our distribution points, people were so desperate. We also reduced up to 40 percent of aid to refugees in Lebanon.”

A man stands on a house that was destroyed by an Israeli airstrike in Hanine village, south Lebanon, on April 25, 2024. The continuing exchange of fire between Hezbollah militants and Israeli forces has displaced thousands of people in southern Lebanon, according to the UNWFP. (AP)

And it is not just displaced communities that the agency has to support. Fleischer said that the number of Lebanese citizens requiring aid had also risen dramatically due to the country’s grinding financial crisis.

Fleischer said that WFP has been able to work with the Lebanese government and the World Bank to gradually integrate those citizens to receive state welfare.

In the south, however, where Israel and Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia have traded fire along the shared border since the conflict began in Gaza, the situation is different.

“We have supported 62,000 people,” said Fleischer, referring to the communities displaced by the cross-border exchanges. “These are both Lebanese citizens and Syrian refugees who have been impacted by the tensions in the south of Lebanon.

“However, if it escalates, the UN and the humanitarian sector will not be able to handle it at this rate. It will exceed the funding and assistance capacity.”