MUMBAI: A parade of India’s business and entertainment elite — many of them supporters of Prime Minister Narendra Modi — went to the polls Monday as the financial capital Mumbai voted in the latest round of the country’s six-week election.

Modi, 73, is widely expected to win a third term when the election concludes early next month, thanks in large part to his aggressive championing of India’s majority Hindu faith.

“My vote is for the BJP and Modi,” said Deepak MaHajjan, 42, who works in banking. “There is no other choice if you care about the future of the economy and business. I have always voted this way.”

Big conglomerates have bestowed upon Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) a campaign war chest that dwarfs its rivals, while Bollywood stars have backed its ideological commitment to more closely align with the country’s majority religion and its politics.

Bollywood actor Shah Rukh Khan (R) with daughter Suhana Khan (L) arrives to cast his ballot to vote at a polling station in Mumbai on May 20, 2024, during the fifth phase of voting of India's general election. (AFP)

Latest data shows that the BJP was by far the single biggest beneficiary of electoral bonds, a contentious political donation tool since ruled illegal by India’s top court.

Leading companies and wealthy businesspeople gave the party $730 million, accounting for just under half of all donations made under the scheme in the past five years.

Conglomerate owners support Modi’s government because it caters to the needs of India’s “existing oligarchic business elite,” Deepanshu Mohan of OP Jindal Global University told AFP.

Lower corporate tax rates, less red tape and a reduction in “municipal regulatory corruption” have also helped Modi win the affection of corporate titans, he said.

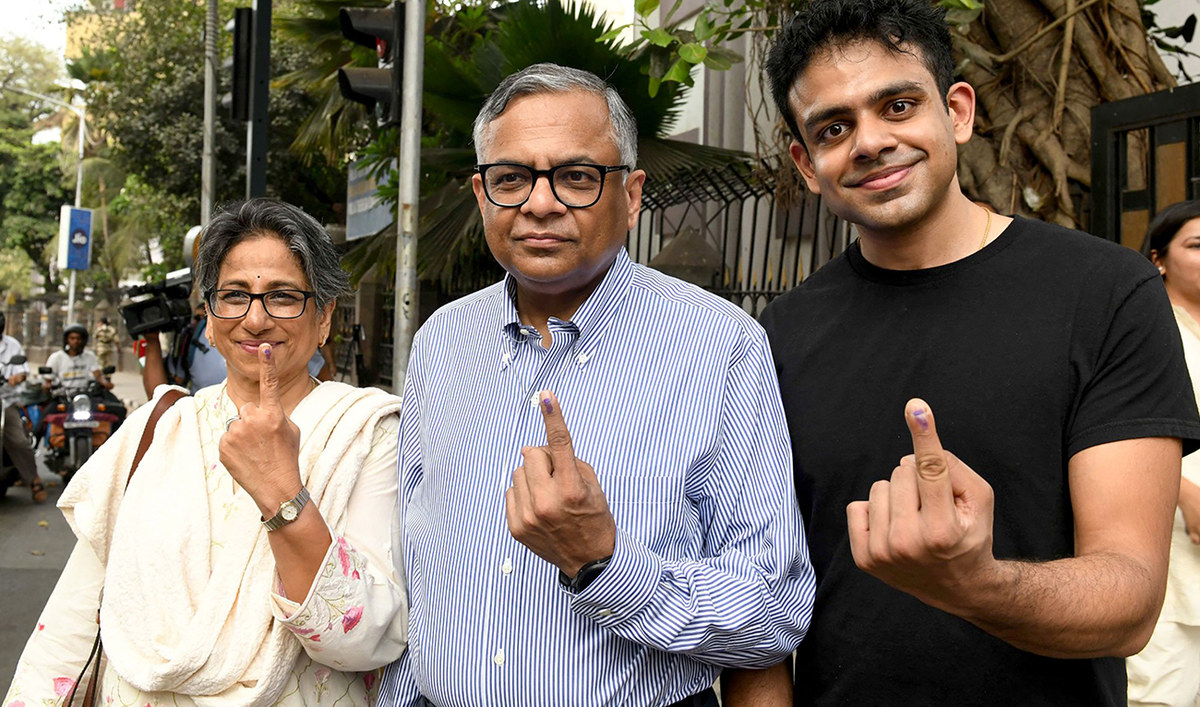

N. Chandrasekaran, the chairman of Tata Sons, a sprawling Indian conglomerate with interests ranging from cars and software to salt and tea, cast his ballot at a polling station in an upper-class Mumbai neighborhood.

Natarajan Chandrasekaran (C) Chairman of the Board at Tata Sons with his wife Lalitha Chandrasekaran (L) shows his inked finger after casting his ballot to vote outside a polling booth in Mumbai on May 20, 2024, during the fifth phase of voting of India's general election. (AFP)

“It’s a great privilege to have the opportunity to vote,” he told reporters.

Asia’s richest man, Reliance Industries chairman Mukesh Ambani, also voted at the same polling station, accompanied by his wife, son, and a media scrum, posing to show his ink-stained finger.

Anand Mahindra, chairman of the eponymous automaker, told news agency PTI after voting: “If you look at the world around us, there is so much uncertainty, there is such instability, there’s terror, there’s war.

“And we are in the middle of a stable democracy where we get a chance to vote peacefully, to decide what kind of government we want. It’s a blessing.”

Modi’s cultivated image as a champion of the Hindu faith is the foundation of his enduring popularity, rather than an economy still characterised by widespread unemployment and income inequality.

A Sadhu or a Hindu holy man shows his ink-marked finger after voting, outside a polling station during the fifth phase of India's general election, in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, India, May 20, 2024. (Reuters)

This year he presided over the inauguration of a grand temple to the deity Ram, built on the grounds of a centuries-old mosque in Ayodhya razed by Hindu zealots in 1992.

Construction of the temple fulfilled a longstanding demand of Hindu activists and was widely celebrated across the country with back-to-back television coverage and street parties.

The ceremony was attended by hundreds of eminent Indians including Ambani, whose family donated $300,000 to the temple’s trust.

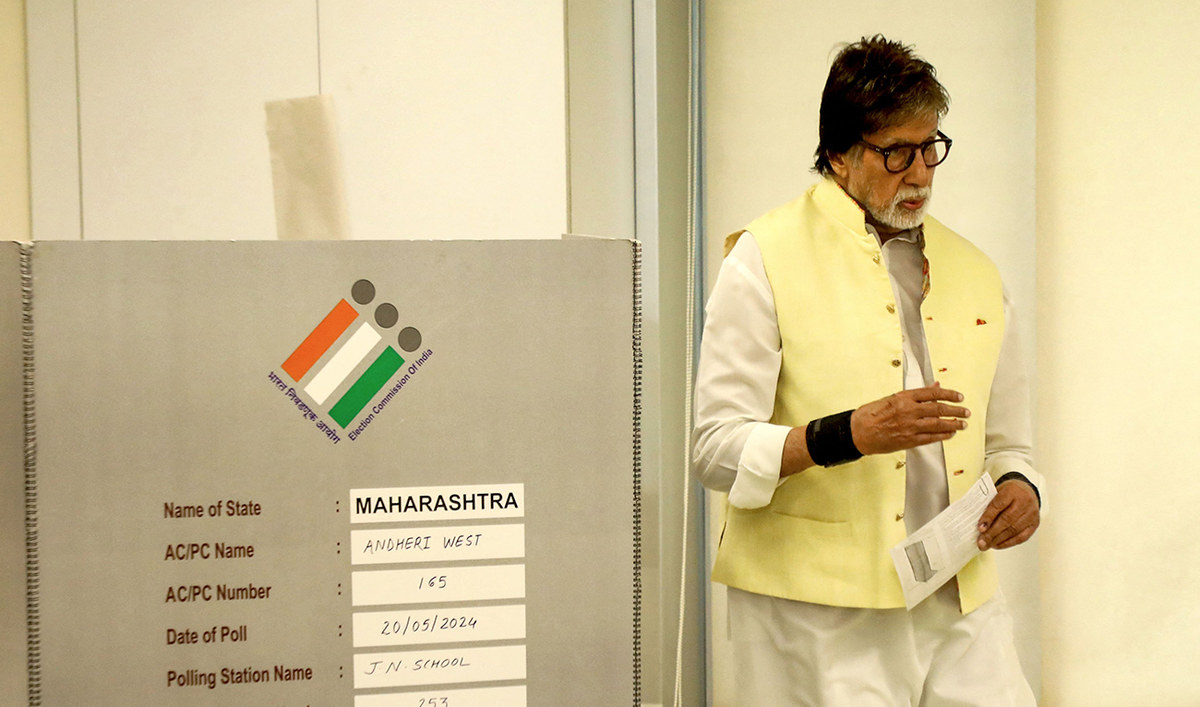

Also present were cricket star and Mumbai native Sachin Tendulkar along with actor Amitabh Bachchan — the single most famous product of Bollywood, as the financial hub’s film industry is known.

Bollywood actor Amitabh Bachchan casts his ballot to vote at a polling station in Mumbai on May 20, 2024, during the fifth phase of voting in India's general election. (AFP)

Numerous screen stars have established themselves as vocal champions of Modi’s administration since he was swept to office a decade ago.

Former soap actor Smriti Irani is one of the government’s most recognized ministers and beat India’s most prominent opposition leader Rahul Gandhi in the contest for her current parliamentary seat in 2019.

Filmmakers have also produced several provocative and ideologically charged films to match the ruling party’s sectarian messaging, which critics say deliberately maligns India’s 200-million-plus Muslim minority.

Last year’s “Kerala Story” was heavily promoted by the BJP but condemned elsewhere for falsely claiming thousands of Hindu women had been brainwashed by Muslims to join the Daesh group.

But some in Mumbai, like delivery driver Sunil Kirti voted for the opposition Congress party.

“In the past year I am earning less, but prices of basic essentials... food and vegetables have gone up,” said Kirti, 29. “Who is to blame for that?“

Bollywood actress Aishwarya Rai Bachchan (R) shows her inked finger after casting her ballot to vote at a polling station in Mumbai on May 20, 2024, during the fifth phase of voting in India's general election. (AFP)

India’s election is conducted in seven phases over six weeks to ease the immense logistical burden of staging the democratic exercise in the world’s most populous country, with more than 968 million eligible voters.

The fifth round is taking place as parts of India endure their second heatwave in three weeks.

Scientific research shows climate change is causing heatwaves to become longer, more frequent and more intense.

Turnout is down several percentage points from the last national poll in 2019, with analysts blaming widespread expectations of a Modi victory as well as the heat.

Temperatures reached 44 degrees Celsius (111 degrees Fahrenheit) in Jhansi in Uttar Pradesh, one of the states where tens of millions of people voted on Monday.