LONDON: It was clear from the moment that British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak stood outside 10 Downing Street on May 22 and announced that he was calling a snap general election that the next six weeks would not go well for his ruling Conservative party.

For many, the raincloud that burst over Sunak’s head as he spoke seemed to sum up the past 14 years, which, riven by factional infighting, saw no fewer than four leaders in the eight years since Theresa May succeeded David Cameron in 2016.

Adding to the comedy of the moment was the soundtrack to the announcement, courtesy of a protester at the gates of Downing Street, whose sound system was blasting out the ’90s pop hit “Things Can Only Get Better” — the theme tune of Labour’s 1997 election victory.

Britain’s Prime Minister Rishi Sunak delivers a speech at a Conservative Party campaign event at the National Army Museum in London. (File/AP)

Headline writers were spoiled for choice. Contenders included “Drown and out,” “Drowning Street” and — probably the winner — “Things can only get wetter.” That last one was also prescient.

In theory, under the rules governing general elections, Sunak need not have gone to the country until December. The reality, however, was that both Sunak and his party were already trailing badly in the polls and the consensus at Conservative HQ was that things could only get worse.

As if to prove the point, in one early Conservative campaign video, the British Union Flag was flown upside down. A series of mishaps and scandals followed, with some Conservative MPs found to have been betting against themselves and the party.

Former British PM Boris Johnson gestures as he endorses British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak at a campaign event in London, Britain, July 2, 2024. (Reuters)

Judging by the steady slide in support for the government, the electorate has neither forgotten nor forgiven the chaos of the Boris Johnson years, typified by the illegal drinks parties held in Downing Street while the rest of the nation was locked down during COVID-19 restrictions.

Nor has the electorate forgotten the failure to deliver on the great promises of Brexit, the shock to the UK economy delivered by the 44-day premiership of Liz Truss, and the inability of the government to control the UK’s borders — which was, after all, the chief reason for leaving the EU.

On the day the election was announced, a seven-day average of polls showed Labour had twice as much support as the Conservatives — 45 percent to 23 percent.

Compounding the government’s woes was the rise of Reform UK, the populist right-wing party making gains thanks largely to the failure of Sunak’s pledge to reduce immigration and “stop the boats” carrying illegal migrants across the English Channel.

On 11 percent, Reform had overtaken the Lib Dems, Britain’s traditional third-placed party, and the vast majority of the votes it seemed certain to hoover up would be those of disenchanted Conservative voters.

By the eve of today’s election, a poll of 18 polls carried out in the seven days to July 2 showed Labour’s lead had eased only very slightly, to 40 percent against the Conservatives’ 21 percent, with Reform up to 16 percent.

Labour Party leader Keir Starmer and Britain’s Prime Minister and Conservative Party leader Rishi Sunak attend a live TV debate, hosted by the BBC. (File/AFP)

On Wednesday, a final YouGov poll on the eve of voting predicted that Labour would win 431 seats, while the Conservatives would return to the new parliament on July 9 with only 102 MPs — less than a third of the 365 seats they won in 2019.

If this proves to be the case, Starmer would have a majority of 212, not only bigger than Tony Blair’s in 1997, but also the strongest performance in an election by any party since 1832.

After the polls close tonight at 10pm, there is a very good chance that Sunak may even lose his own seat, the constituency of Richmond and Northallerton, which the Conservatives have held for 114 years.

Either way, the Conservative party will be thrust into further turmoil as the battle begins to select the party’s next leader who, as many commentators are predicting, can look forward to at least a decade in opposition.

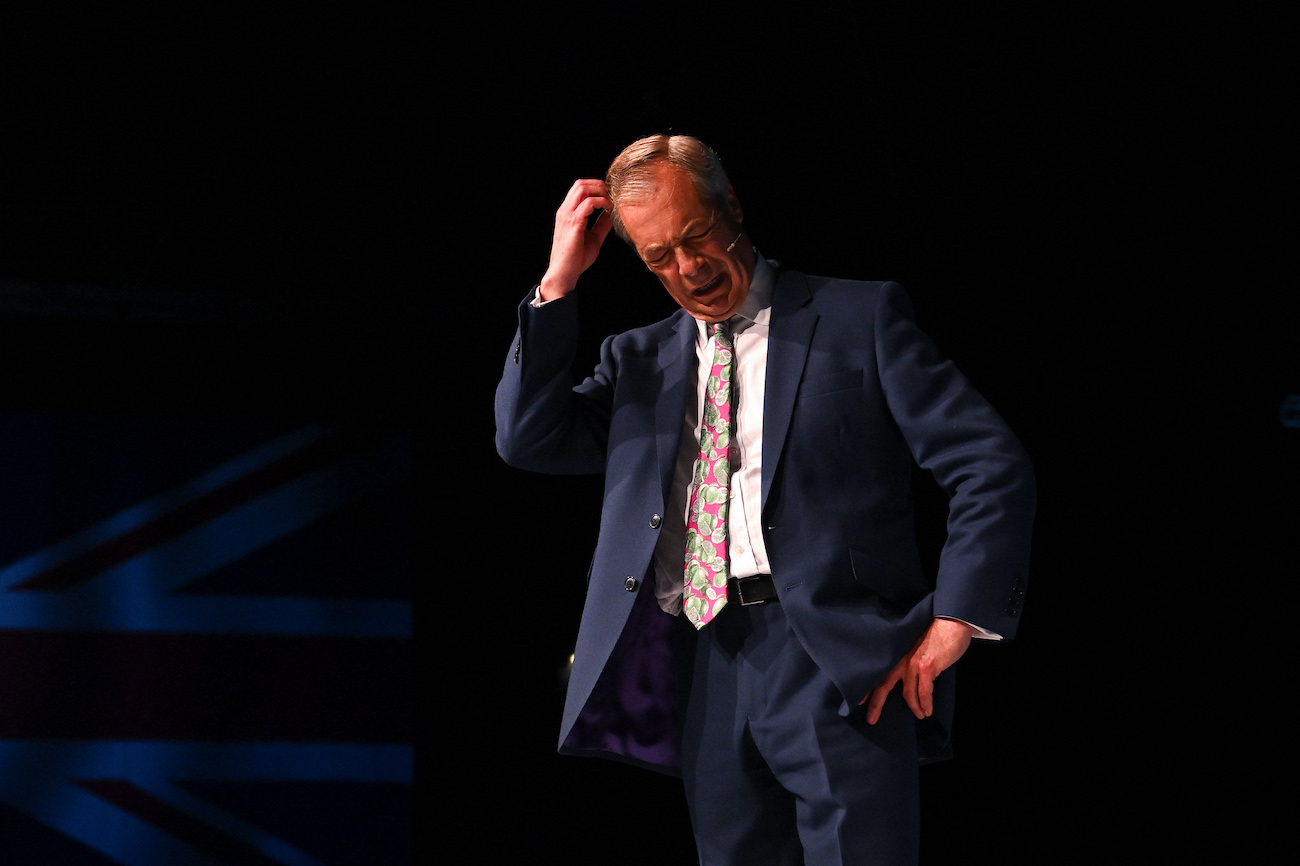

Reform UK leader Nigel Farage scratches his head as he delivers a speech during the “Rally for Reform” at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham. (File/AFP)

The return of Labour, a completely regenerated party after 14 years in the wilderness, is likely to be good news for Britain’s relationships in the Middle East, as Arab News columnist Muddassar Ahmed predicted this week.

Distracted by one domestic or internal crisis after another, the Conservatives have not only neglected their friends and allies in the region but, in an attempt to stem the loss of its supporters to Reform UK, have also pandered to racial and religious prejudices.

“The horrific scenes unfolding in Gaza, for example, have rocked Muslims worldwide while pitting different faith communities against one another,” Ahmed wrote.

A Palestinian boy who suffers from malnutrition receives care at the Kamal Adwan hospital in Beit Lahia in the northern Gaza Strip on July 2, 2024. (AFP)

“But instead of working to rebuild the relationships between British Muslims, Jews and Christians, the Conservative government has branded efforts to support Palestinians as little more than insurgent ‘hate marches’ — using the horrific conflict to wedge communities that ought to be allied.”

On the other hand, Labour appears determined to reinvigorate the country’s relationship with a region once central to the UK’s interests.

January this year saw the launch of the Labour Middle East Council (LMEC), founded with “the fundamental goal of cultivating understanding and fostering enduring relationships between UK parliamentarians and the Middle East and North Africa.”

Chaired by Sir William Patey, a former head of the Middle East Department at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and an ambassador to Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Sudan, and with an advisory board featuring two other former British ambassadors to the region, the LMEC will be a strong voice whispering in the ear of a Labour government that will be very open to what it has to say.

Britain’s Labour Party leader Keir Starmer speaks on stage at the launch of the party’s manifesto in Manchester, England, Thursday, June 13, 2024. (AP)

Writing in The House magazine, Sir William predicted “a paradigm shift in British foreign policy is imminent.”

He added: “As a nation with deep-rooted historical connections to the Middle East, the UK has a unique role to play in fostering a stable and prosperous region.”

The role of the LMEC would be “to harness these connections for a positive future. We will work collaboratively to address pressing global issues, from climate change to technological advancement, ensuring that our approach is always one of respect, partnership, and shared progress.”

David Lammy, Labour’s shadow foreign secretary, has already made several visits to the region since Oct. 7. In April he expressed “serious concerns about a breach in international humanitarian law” over Israel’s military offensive in Gaza.

Britain’s main opposition Labour Party Shadow Foreign Secretary David Lammy addresses delegates at the annual Labour Party conference in Liverpool. (File/AFP)

It was, he added, “important to reaffirm that a life lost is a life lost whether that is a Muslim or a Jew.” In May, Lammy called for the UK to pause arms sales to Israel.

In opposition, Labour has hesitated to call for a ceasefire in Gaza, but this has been a product of its own internal and domestic tensions. Starmer has brought the party back on track after years of accusations by UK Jewish activist groups that under his predecessor Jeremy Corbyn it was fundamentally antisemitic.

Whether the charges were true, or whether the party’s staunch support of the Palestinian cause was misrepresented as antisemitism, was a moot point. Starmer knew that, in the run-up to a general election, this was hard-won ground that he could not afford to lose.

Nevertheless, even as he has alienated some Muslim communities in the UK for his failure to call for a ceasefire, he has spoken out repeatedly against the horrors that have unfolded in Gaza.

A protester looks on in Parliament Square, central London, on June 8, 2024 at the end of the “National March for Gaza”. (File/AFP)

Crucially, he has consistently backed the two-state solution, and the creation of “a viable Palestinian state where the Palestinian people and their children enjoy the freedoms and opportunities that we all take for granted.”

In broader terms, Lammy has also made clear that Labour intends to re-engage with the Middle East through a new policy of what he called “progressive realism.”

Less than a week before Sunak called his surprise general election, Lammy spoke of the need for the UK to mend relations with the Gulf states, which he saw as “hugely important for security in the Middle East” and “important in relation to our economic growth missions.”

Because of missteps by the Conservative government, he added, relations between the UAE and the UK, for example, were at “an all-time low. That is not acceptable and not in the UK’s national interests (and) we will seek to repair that.”

In an article he wrote for Foreign Affairs magazine, Lammy went further.

China, he said, was not the world’s only rising power, and “a broadening group of states — including Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE — have claimed seats at the table. They and others have the power to shape their regional environments, and they ignore the EU, the UK, and the US ever more frequently.”

Lammy expressed regret for “the chaotic Western military interventions during the first decades of this century,” in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, which had proved to be a “recipe for disorder.”

As shadow foreign secretary, he has traveled extensively across the MENA region, to countries including Bahrain, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkiye, the UAE, and the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

All, he wrote, “will be vital partners for the UK in this decade, not least as the country seeks to reconstruct Gaza and — as soon as possible — realize a two-state solution.”

For many regional observers, Labour is starting with a clean sheet, but has much to prove.

“It is an acknowledged fact among scholars that foreign policies don’t radically change after elections,” Arshin Adib-Moghaddam, professor in global thought and comparative philosophies at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, told Arab News.

“Therefore, I don’t expect major shifts once Labour forms the government in the UK.

“That said, the composition of the Labour party and its ‘backbench’ politics are likely to shift the language and probably even the code of conduct, in particular with reference to the question of Palestine. For a Labour leader it may be that much more difficult to be agnostic about the horrific human rights situation in Gaza.”

Displaced Palestinians flee after the Israeli army issued a new evacuation order for parts of Khan Yunis and Rafah on July 2, 2024. (AFP)

For political analysts advising international clients, however, the implications of a Labour victory extend beyond the situation in Gaza.

“In an attempt to secure political longevity, the party will renegotiate key policy priorities in the Middle East,” said Kasturi Mishra, a political consultant at Hardcastle, a global advisory firm that has been closely following the foreign policy implications of the UK election for its clients in business and international politics.

“This could include calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, ending arms sales to Israel, reviving trade and diplomacy with the Gulf states and increasing the UK’s defense spending in the region,” Mishra told Arab News.

“This renegotiation is important at a time when the UK finds itself increasingly uncertain of its global position.

Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan meets with Shadow Foreign Secretary of the British Labor Party David Lammy on the sidelines of the Manama Dialogue 2023 held in Bahrain. (SPA)

“The Middle East has significant geopolitical and security implications for the West. Labour policy-makers recognize this and are likely to deepen British engagement with the region to reshape its soft power and influence.”

Mishra highlighted Lammy’s multiple trips to the region as a foretaste of a Labour’s intention to strengthen ties with the Gulf states, “which have been neglected in post-Brexit Britain.

“Given the influential role of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar in regional security and the potential to collaborate with them on climate mitigation and other international issues, it is clear that he will seek to forge partnerships.

“His doctrine of progressive realism combines a values-based world order with pragmatism. It is expected that he will favor personalized diplomacy, more akin to that of the UAE, India and France.”