KARACHI: With a backpack slung over his shoulder, Habib Hussain Abbasi, 74, turned into a street off Karachi’s bustling Napier Road and lifted the shutter to open “Abbasi Kutubkhana.”

Established as a roadside stall in 1910 by Abbasi’s maternal grandfather Ghulam Abbas Dawoodbhai in Juna Market, Abbasi Kutubkhana now stands as the port city’s oldest bookstore.

Located in a 48-square-yard space with a ground and a mezzanine floor, the store houses over 6,000 books on a variety of topics. New titles as well as many that are over 60 years old are available in several languages, including Urdu, Arabic, Persian, English, Pashto, Sindhi, Punjabi, and Saraiki.

“It’s like you have arrived from a desert to an oasis,” Abbasi told Arab News in an interview one morning this month as he entered his bookstore, which he described in its heyday as a vibrant space frequented by Karachi’s writers, poets, scholars and politicians.

The picture taken on July 27, 2024, shows Karachi’s bustling Napier Road, where Habib Hussain Abbasi's book shop is situated. (AN photo)

Abbasi himself started sitting at the store when he was in the fourth grade, he said, coming straight from school in his uniform to assist his father.

“I would change here, have my lunch and start helping my father,” he recalled. “Still every day I ache to come here. For me it is like having food, if I don’t come here for a day, I feel like I’m hungry.”

Around the bookstore, one can find stalls of street food like jalebis and samosas and shops selling crockery, hardware, spices and shoes but there are no other bookstores in sight.

That was not always the case.

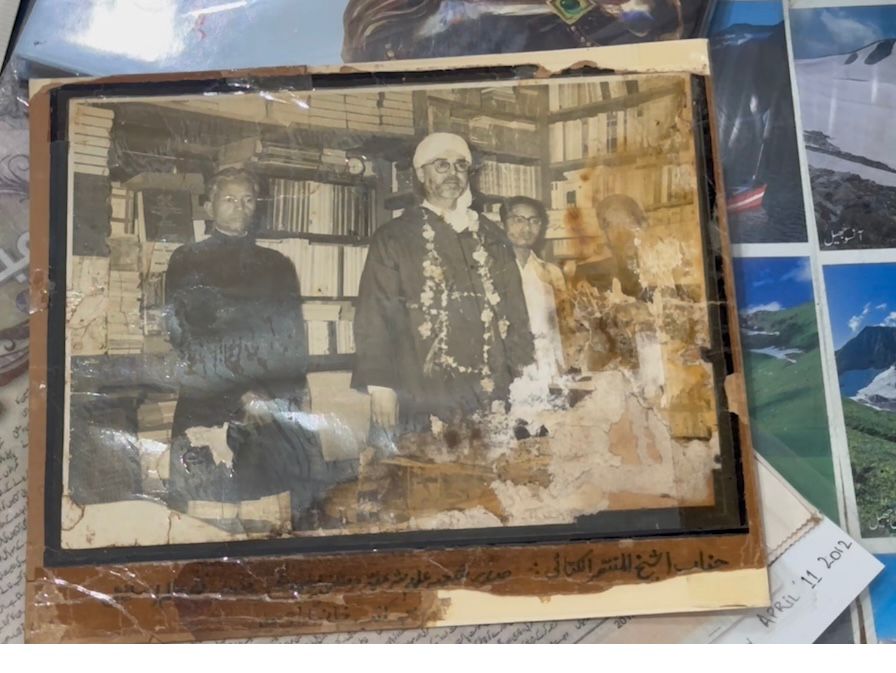

The photo provided by Habib Hussain Abbasi on July 27, 2024, shows Sheikh Al Muntasir Al Qahtani (right), a scholar and Vice Chancellor of Damascus University, visiting “Abbasi Kutubkhana” in 1963. (AN photo)

After Pakistan gained independence in 1947, Abbasi said, around a dozen bookstores emerged in Juna Market, making it the go-to area for Karachi’s book lovers.

“Earlier there used to be many bookstores here, at least 10-12,” the shop owner said.

“Slowly they started diminishing, to the point that now only my bookstore is left ... reaching this place [Juna Market] is a task in itself.”

But the shop’s vast collection means if one can’t find a book elsewhere in the city, they will eventually still make the hike to Juna Market and end up at Abbasi Kutubkhana.

“A customer came looking for some specific books which were not available in the market, hence I have come here looking for those books,” said Nizamuddin Khan, a customer at Abbasi’s shop who himself owns a bookstore in the city’s Urdu Book Bazaar.

“Generally, if a customer needs a book that is out of stock anywhere in Pakistan and has very little chance of being found, there is a 90 percent chance they will find it here.”

And Abbasi does not mind if you aren’t a paying customer.

“If they come and sit here, read the book, take notes or make photocopies, they are fully allowed to do so,” he added.

While Abbasi has carried on his grandfather’s and father’s legacy of managing the bookstore for 60 years, none of his three children have opted to join the family business.

That worries the septuagenarian.

“I need to think about the bookstore’s future,” he said, particularly in an era when online sales have been driving independent bookstores out of business across the world:

“It would have been a wise decision on my part if I had pursued that direction [of setting up an online bookstore], it would have helped me significantly. From the beginning, I did not lean toward that approach … Sometimes, I hold myself responsible and question why I didn’t … Had I done so, it would have created more ease for people as well.”

Pointing at other shops in the street, Abbasi said:

“Sandals or shoes are displayed in beautiful glass showcases while books are being sold on footpaths. This is a huge tragedy when it comes to books.”

Then he paused, and added:

“But God willing, I won’t let that happen to this bookstore.”