DUBAI: When the UN launched the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, it set out a bold action plan to eliminate premature death and needless suffering caused by preventable diseases by 2030.

With just five years to go, the world appears to be moving backwards. Indeed, 2024 actually witnessed an alarming surge in a triad of preventable or manageable child-killer diseases.

Dengue, cholera and mpox returned with a vengeance, claiming the lives of thousands of children. With their weaker immune systems, the young are particularly vulnerable to infection and often fatal complications.

Bangladeshi children suffering from dengue fever rest at a ward at the Mugda Medical College and Hospital in Dhaka on August 8, 2019. (AFP file)

This multifaceted health emergency has compounded the suffering of already stricken communities in impoverished countries and conflict zones, where climate change, inequality and underfunded health systems have left many without access to basic care or sanitation.

“Currently, about half of the world’s population is not fully covered by essential, quality, affordable health services, denying them their right to health,” said Dr. Revati Phalkey, global health and nutrition director at Save the Children International.

“Health systems are under enormous pressure to deliver universal health coverage, with the majority of countries experiencing worsening or no significant change in service coverage since the launch of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015.”

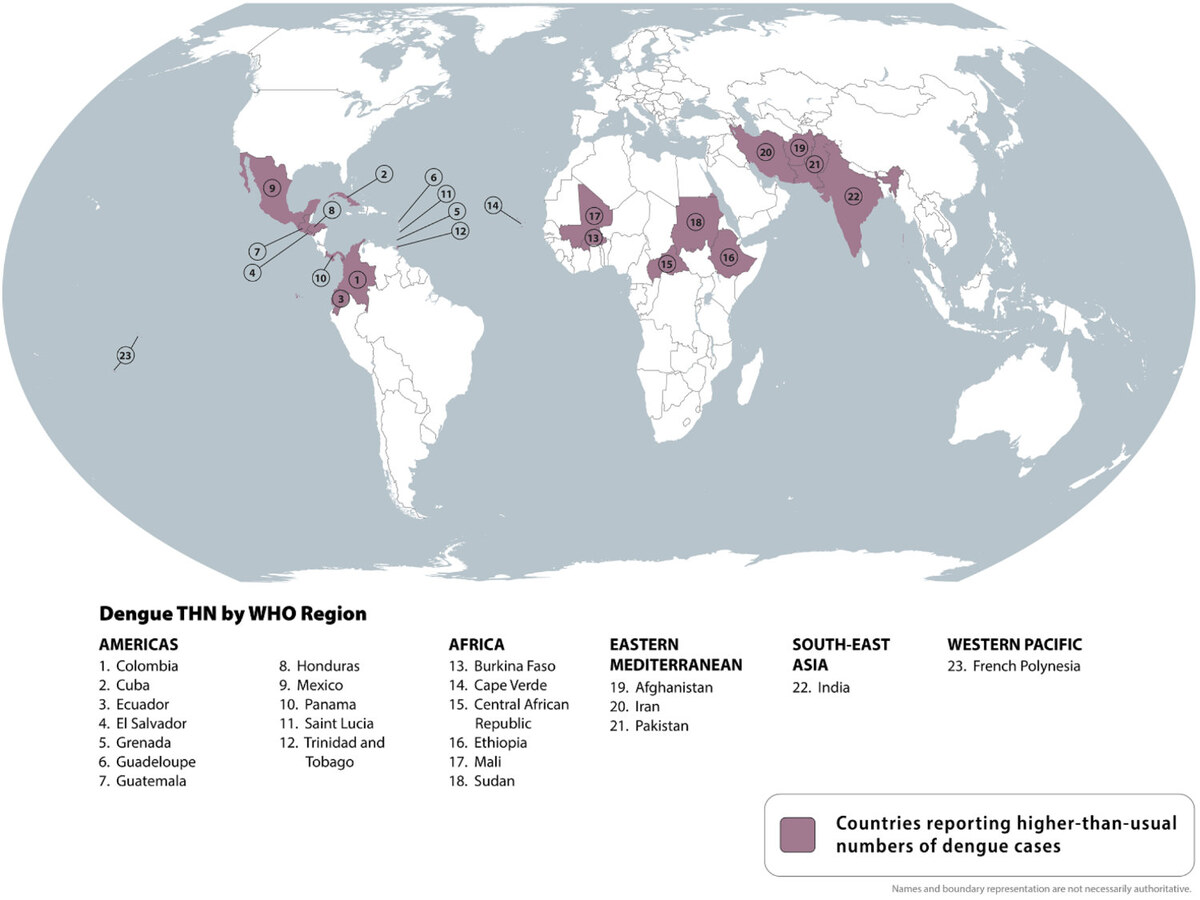

According to the World Health Organization, dengue fever — a mosquito-borne disease that causes severe fever, pain and in some cases death — saw an alarming spike in 2024.

Dengue cases doubled from 6.65 million in 2023 to 13.3 million in 2024. The total number of dengue-related deaths globally last year was 9,600. The WHO estimates some four billion people are now at risk of dengue related viruses.

A woman carries her children while workers spray mosquito repellent as part of a prevention campaign against dengue fever in Banda Aceh on January 22, 2025. (AFP)

Children who play outside with limited protection against mosquitoes are often more exposed and therefore more vulnerable to the virus than adults. The absence of mosquito nets where children sleep is also a key contributing factor.

In developing countries in Southeast Asia, parts of Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, dengue fever is especially prevalent. Informal settlements in these regions often lack basic infrastructure for waste management, sewage or clean water.

Infographic courtesy of US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

These conditions offer a fertile breeding ground for mosquitoes and for the disease to spread. Meanwhile, rising temperatures associated with climate change have expanded the range of mosquito habitats, allowing them to flourish across a wider region.

The spread of dengue, sometimes known as “breakbone fever” due to the severe fatigue it causes, represents “an alarming trend” according to WHO Director General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebereyesus, with 5 billion people at risk of being infected by 2050.

FASTFACT

13,600

Deaths from dengue, cholera, or mpox in 2024.

Dengue is not the only danger. In Yemen, Sudan and Gaza, where conflict has displaced thousands and destroyed critical civilian infrastructure, cholera has become a major threat to adults and children alike.

A deadly bacterial infection spread through contaminated water, cholera is another consequence of poor sanitation. The infection causes rapid dehydration through severe diarrhea and vomiting, which can quickly lead to death if left untreated.

The UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East released a statement in June warning of a cholera outbreak in the Gaza Strip amid severe water shortages and damage to sanitation services.

A woman and children sit outside tents sheltering displaced Palestinians in Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip on February 8, 2024, amid the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Palestinian militant group Hamas. (AFP file)

Several UN agencies have issued warnings about the high risk of infectious diseases in overcrowded refugee camps across the Middle East and North Africa, where displaced households have limited access to clean water and proper sanitation.

In Sudan, as of last November, the WHO reported more than 37,514 cholera cases across the country and at least 1,000 deaths. “We are racing against time,” Sheldon Yett, the UN children’s fund representative to Sudan, said in a statement in September.

“We must take decisive action to tackle the outbreaks as well as invest in the health systems underpinning the essential services vulnerable children and families in Sudan so desperately need.”

A health care worker attends to a young patient at a cholera treatment center in Gedaref state, Sudan, November 2024. (Photo courtesy of UNOCHA / Yao Chen)

Despite efforts by the international community to provide vaccines and clean water, outbreaks in conflict zones have proven difficult to keep under control. The collapse of sanitation services, in particular, has left millions of children vulnerable to the disease.

Although the overall number of cholera cases worldwide fell by 16 percent in 2024, there has been a 126 percent spike in the number of deaths as a result of the disease.

Another health crisis threatening the world’s children is mpox, formerly known as monkeypox. The virus reemerged in 2024 to devastating effect across parts of Africa, with children suffering the most severe consequences.

Once a rare disease confined to rural areas of Central and West Africa, mpox has now become a significant public health crisis with thousands of reported infections, particularly among children under the age of five.

Mpox, contracted through contact with infected people and animals, bodily fluids and contaminated objects, causes fever, rashes, and painful lesions that in turn can lead to other illnesses and afflictions such as pneumonia and blindness.

While it can be controlled using vaccines, such resources remain scarce in parts of Africa. Having already been overwhelmed by Ebola and malaria, the region’s health systems are stretched to the limit, leaving treatment out of reach for thousands of children.

Moreover, poor sanitation, crowded living conditions, and rapid urbanization have increased the risk of transmission.

Dr. Robert Musole, medical director of the Kavumu hospital, visits patients recovering from mpox in the village of Kavumu, 30km north of Bukavu in eastern DR Congo on August 24, 2024. (AFP file)

Children in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo have been the worst affected by the mpox virus, with the WHO declaring the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern. Around 75 percent of cases are in children under the age of 10.

The surge in these diseases reflects the broader, interconnected crises faced by the world, where the most vulnerable populations are left with limited means to recover and adapt.

In wealthier countries, child deaths resulting from cholera and dengue have dropped significantly thanks to well-functioning sanitation services and accessible healthcare systems that have weathered the blows of the coronavirus pandemic.

A boy carries a child to receive treatment at a medical centre near a camp for people displaced by conflict in Abs in Yemen's Hajjah province on August 27, 2024. (AFP)

However, in low income countries, particularly those in the midst of conflict, healthcare systems are extremely vulnerable, with medical staff overstretched, medicines in short supply, and wards overwhelmed by the sick and wounded.

The grim reality for millions of children across the world underscores the urgent need for global action.

“We need greater global investments to build strong health systems that are able to deliver essential health services, especially vaccines and essential medicines, while responding to global health emergencies including emerging issues like mpox,” said Dr. Phalkey.

A medic gives the cholera vaccination to a child in the town of Maaret Misrin in the rebel-held northern part of the northwestern Idlib province on March 7, 2023. (AFP

“It is time for governments and the international community to step up and ensure all children are protected against disease and have access to adequate health services when they need them and where they need them.

“Every child has the right to survive and thrive, and it is our collective responsibility to deliver on this.”