LONDON: One day after the surprising agreement between the Syrian Arab Republic’s interim government and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, there are reports of a similar pact in the offing between the government and Druze representatives in the Suwayda province.

The imminent agreement allows the Syrian authorities’ security forces access into the Druze stronghold in southern Syria, through liaison and cooperation with the two military leaders Laith Al-Bal’ous and Suleiman Abdul-Baqi, as well as local notables.

The agreement includes allowing the Suwayda population to join the government’s defense and security forces, and secure government jobs. It also grants the Druze community full recognition as a constituent part of the Syrian people.

In return, all security centers and facilities throughout the province will be handed to the interim government’s General Security Authority.

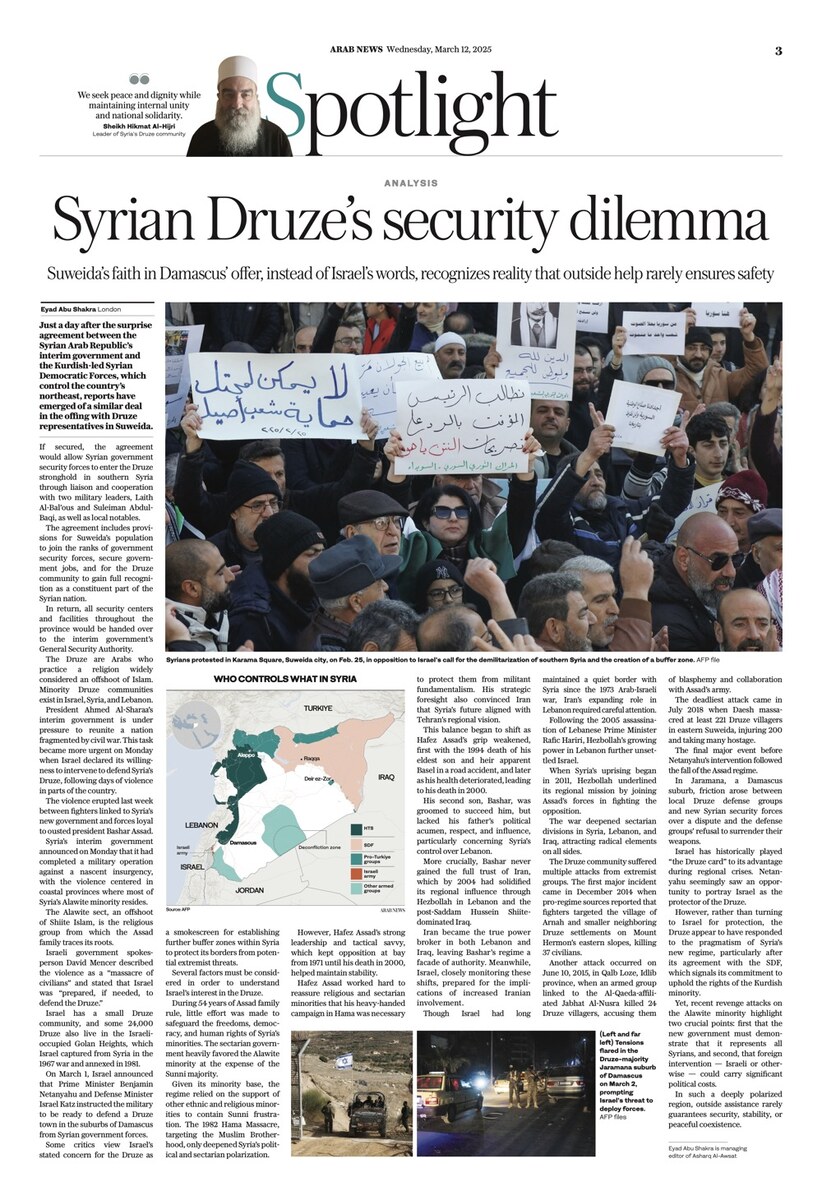

The Druze, who are spread across Syria, Lebanon and Israel, are an esoteric Islamic sect that branched out of Ismaili Shiism. (AFP/File)

Background to the developments

The fluid political situation in Syria was always destined to have regional repercussions because it is one of the most strategically important nations in the Near East.

The announcement by Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that Tel Aviv was committed “to protecting the Druze community in southern Syria” did not come as a surprise.

This was particularly so for observers who have been watching the unfolding saga closely since the 2011 Syrian uprising against the Bashar Assad regime.

Several factors must be taken into consideration when attempting to understand what is going on.

Importantly, one needs to remember that the 54-year-old regime of the Assads has not helped to safeguard freedoms, democracy and human rights.

The sectarian and police state gave huge advantages to the Assad clan’s Alawite minority, at the expense of the Sunni majority that makes up more than 75 percent of Syria’s population.

Israel has a small Druze community, and some 24,000 Druze also live in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, which Israel captured from Syria in the 1967 war and annexed in 1981. (AFP/File)

Rule under the two former presidents

The regime, given its minority base, also had to rely on the support of other religious minorities in confronting the continuing frustration of the Sunnis.

The 1982 Hama Massacre against the Muslim Brotherhood intensified the animosity and distrust, and pushed the country further down the road of political and sectarian polarization.

However, during that period the strong leadership and tactical savviness of Hafez Assad, who ruled between 1971 and his death in 2000, kept opposition at bay.

The regime had worked hard to reassure religious and sectarian minorities that its heavy-handed campaign in Hama was necessary to save them from supposed Islamist fundamentalism.

Hafez Assad’s shrewd reading and handling of the regional situation convinced the Iranian regime — his trusted ally since the 1980 to 1988 Iran-Iraq war — that its vision in the Near East was in safe hands.

That situation began to change when Hafez Assad’s grip on the regime began to weaken. There was first the death of his eldest son and heir apparent Basel in a road accident in 1994, and then his health deteriorated until his death in 2000.

Syria’s interim government announced on Monday that it had completed a military operation against a nascent insurgency. (AFP/File)

Bashar’s Syria

Hafez Assad’s second son Bashar, a medical doctor, who was groomed to be the heir after Maher’s death, became the de-facto leader with most of the political responsibilities, alliances and personnel.

However, Bashar did not have his father’s savviness and expertise. He further lacked widespread respect inside his father’s regime, and with the latter’s regional allies.

Many of his father’s veteran political and military lieutenants were marginalized. In addition, there was a sidelining of many of his father’s allies in Syria, as well as Lebanon, which had become a politically subservient entity.

More importantly, perhaps, Bashar did not gain the respect and trust of Iran, which by 2004 had become a powerful regional player, both in Lebanon through Hezbollah, and the post-Saddam Hussein Shiite-dominated Iraq.

In fact, Iran became the real power broker in both Lebanon and Iraq, leaving Bashar’s regime as a facade of influence.

In the meantime, Israel, which was keenly monitoring the change at the top in Syria, was preparing to deal with more Iranian involvement.

Some critics view Israel’s stated concern for the Druze as a smokescreen for establishing further buffer zones within Syria to protect its borders from potential extremist threats. (AFP/File)

Syria as viewed by Israel

Israel had been reassured of its peaceful borders with Syria since the war of 1973. Tel Aviv always believed that, despite the tough rhetoric, the Assad regime would pose no threat to its occupation of the Golan Heights.

However, Iran’s direct involvement in Lebanon required extra attention but the Israelis were not too worried. They believed Iran would never challenge the US in the region.

Still, Iran’s constant supposed blackmail was not a comforting scenario, against the background of its nuclear ambitions. Moreover, Hezbollah became a serious irritant.

Following the assassination of Lebanon’s former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in 2005, Hezbollah had increasing power, influence and confidence. It had a powerful grip on Lebanon’s politics, and control of the country’s southern borders with Israel.

The 2006 border war between Hezbollah and Israel was a significant development. It ended with Hezbollah turning its attention from the south to the Lebanese interior in 2008, when it attacked Beirut and Mount Lebanon.

The 2011 Uprising

After the 2011 Syrian uprising, Hezbollah underlined its regional mission when it joined the Syrian regime’s army to fight the rebels, along with several Shiite militias aligned with groups in Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The Syrian uprising, that would deteriorate into one of the region’s bloodiest wars, claimed about a million lives, displaced more than 10 million, and left many cities and villages in ruin.

The war widened, as never before, the sectarian divide in Syria, as well as in Lebanon and Iraq. More radical elements, local and foreign, joined the warring sides, further fueling fears.

As for the Druze community, it suffered like many others, especially in the conflict zones. Several Druze-inhabited areas were attacked or threatened by armed radical groups.

In such a deeply polarized region, outside assistance rarely guarantees security, stability, or peaceful coexistence. (AFP/File)

Attacks and fears

The first deadly attack was in December 2014 and claimed the lives of 37 civilians.

As reported by pro-regime sources, it targeted the village of Arnah and smaller neighboring Druze villages, on the eastern slopes of Mount Hermon in the Golan Heights.

The second took place on June 10, 2015, in the village of Qalb Lozeh in the northwestern province of Idlib by an armed group from Jabhat Al-Nusra, led by a certain Abdul-Rahman Al-Tunisi.

The attackers tried to confiscate the houses of villagers they accused of blasphemy and cooperating with Assad’s army, resulted in the killing of 24.

The worst attacks, however, were carried out by Daesh which targeted eight villages in the eastern part of the Suwayda province in July 2018, with 221 villagers killed and 200 others injured, in addition to many taken hostage.

Several factors must be considered in order to understand Israel’s interest in the Druze. (AFP/File)

The final event before Netanyahu’s controversial intervention, happened after the new Syrian Interim Government brought down Al-Assad’s regime.

Friction in the Damascus Druze suburb of Jeramana, between local Druze ‘defense groups’ and the ‘New” Syrian Army resulted from a quarrel, and the refusal the ‘defense groups’ to hand over their weapons.

The situation became intense as the Army was already facing challenges to its authority in other parts of the country, including the Alawite heartland in Lattakia and Tartous Provinces (northwest), and northeastern Syria where the Kurdish-majority SDF were active.

Israel, where more than 120 thousand Druze live, has always tried to play ‘The Druze Card’ during regional tension. Actually, the policy of ‘Divide and Rule’ has always proven to work in the Levant, and the Israeli Prime Minister felt the opportunity was there to score another political, by portraying Israel as the protector of the Druze.

He is surely aware of the ‘the protector of the Shiites’ role played by Iran, the ‘defender of the Sunnis’ claimed by Turkish Islamists, and of course, ‘the old supporters of Christendom’ by some conservative Western governments. Thus, Israel, in Netanyahu’s calculations cannot lose.

However, the surprising development with the SDF of northeastern Syria seems have to reassured the Druze of the pragmatism of the new Damascus regime. Also, the sad events in the northwest carried two warning signs to all involved:

The first is that the new regime must prove that it is a ‘government of all Syria’; and thus, be responsible for the well-being of all constituent Syrian communities.

The second is that any ‘foreign help’ may be politically costly; and in an acutely polarized region, such ‘help’ would not insure any safety, security or peaceful coexistence in return.