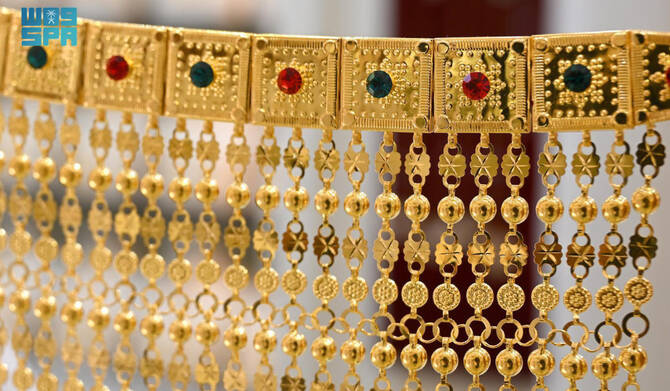

RIYADH: Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province has, historically, been a hub for the making of gold jewelry. Families in Al-Ahsa and Qatif have been passing down this intricate art for centuries, forging the region’s cultural identity and fueling its commerce.

While some artisans have shifted to gold trading or other careers amid the Kingdom’s economic transformation, many continue to practice their craft, according to the Saudi Press Agency.

Mohammed Al-Hamad, former head of the Gold and Jewelry Committee at the Asharqia Chamber of Commerce and Industry, shared insights into the historical development of this profession in an interview with the SPA.

While some artisans have shifted to gold trading or other careers amid economic transformation, many continue to practice their craft. (SPA)

Al-Hamad comes from a long line of jewelry manufacturers and gold traders. He described the traditional methods of shaping gold using rudimentary tools to create distinctive jewelry. He explained that the traditional goldsmithing process began with melting gold in a crucible over hot coals using a leather bellows, followed by shaping it with a hammer and anvil, the essential tools of the trade.

According to Al-Hamad, early goldsmiths were not only skilled artisans but also adept merchants, engaging directly with customers in their shops, selling their creations, and reworking precious metals brought in by patrons.

Some even traveled extensively to trade in used gold, silver, and the gold embroidery of traditional cloaks (bisht), using scales and traditional weight measurements before the widespread adoption of the gram system.

FASTFACT

Early Saudi goldsmiths were not only skilled artisans but also adept merchants, engaging directly with customers in their shops and reworking precious metals brought in by patrons.

Transactions were often based on trust, with gold frequently sold on credit or entrusted to the goldsmith for repair or modification.

This change has sparked customer demand for unique designs, encouraging jewelers to use advanced machinery to innovate. (SPA)

Al-Hamad recalled that, as a child, he accompanied his father to purchase a 10-tola gold ingot —about 116 grams — for SR 600, a hefty sum back then.

He also mentioned a remarkable relic of the craft’s storied past — a legal document more than 200 years old recording the sale of a gold sandal, a testament to the artistry’s deep roots in the Eastern Province.

Artisans, he said, often crafted their own specialized tools and displayed their finished pieces in a traditional box known as a matbakah.

While some artisans have shifted to gold trading or other careers amid economic transformation, many continue to practice their craft. (SPA)

As Saudi Arabia’s economy grew and diversified, many goldsmiths pivoted from hands-on crafting. Some opened shops, workshops, or even factories, while others pursued opportunities in national companies or government positions.

Al-Hamad sees his generation as a bridge, connecting the days of pure handcrafting to a new era of gold trading and specialized workshops.

Jaafar Al-Nasser, a young electrical engineering graduate from the US, chose to carry forward his family’s goldsmithing legacy, the SPA reported.

He has built a factory packed with cutting-edge technology. Al-Nasser said that the gold and jewelry industry has transformed dramatically, shaped by economic, cultural, and social shifts, particularly greater exposure to international cultures.

This change has sparked customer demand for unique designs, encouraging jewelers to use advanced machinery to innovate.

Al-Nasser said soaring gold prices have hit the industry hard. Larger pieces are costlier to craft, pushing designers to create lightweight jewelry. This focus on minimal weight is a core goal for today’s manufacturers, he noted — a delicate balance of artistry and practicality driving this traditional craft forward.