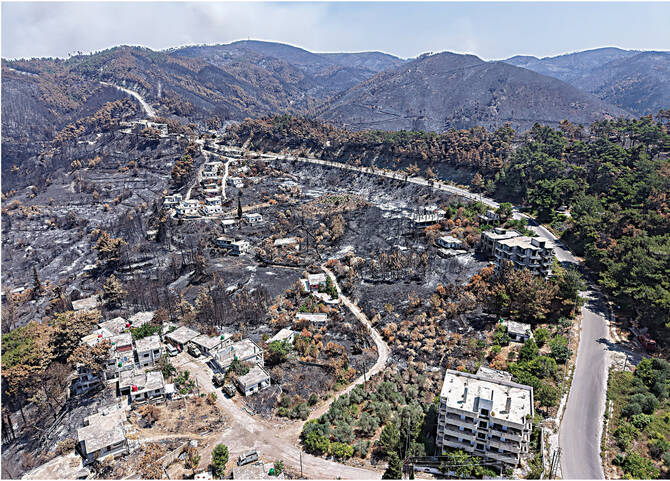

LONDON: Wildfires swept across Syria’s northwestern Latakia province this month, scorching more than 16,000 hectares of forest and farmland, damaging 45 villages, displacing thousands of civilians, and fragmenting the fragile livelihoods of rural communities.

On July 2, fast-moving fires erupted in the mountainous, densely wooded northern countryside of Latakia, escalating rapidly into a full-blown emergency. Fueled by extreme temperatures, dry conditions, and strong seasonal winds, the fires surged across rugged terrain with little resistance.

After nearly two weeks of relentless burning, Syrian authorities declared the fires fully contained on July 15. Firefighting crews from Turkiye, Iraq, Lebanon, Qatar and Jordan joined Syrian civil defense units in the battle to control the flames, which raged through difficult-to-access forested highlands.

Smoke rises into the sky during a wildfire near the town of Rabia, Syria, in the Latakia countryside,on July 6, 2025. (AP)

At a joint press conference, Latakia Governor Mohammad Othman and Emergency and Disaster Management Minister Raed Al-Saleh outlined the formidable challenges crews faced. These included landmines, unexploded ordnance, winds exceeding 60 kph, and an absence of firebreaks after years of forest neglect.

Although the flames have been extinguished, the crisis is far from over. “The flames are gone, but the mission has just begun,” Al-Saleh said, cautioning that the long-term effects of the fires could endure for years.

Recovery efforts are now focused on rehabilitating burned land and aiding thousands of displaced families.

The fire’s aftermath has compounded an already dire humanitarian crisis in a region battered by more than a decade of war and economic collapse. Entire harvests — a vital source of food and income — have been lost, and returning residents find their homes and farms reduced to ashes.

A Turkish helicopter helps battle a forest fires in the coastal Syrian province of Latakia on July 5, 2025. (AFP)

Among the most severely affected areas are Qastal Maaf, Rabeea, Zinzaf, Al-Ramadiyah, Beer Al-Qasab, Al-Basit and Kassab, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

“The humanitarian situation is catastrophic,” said Rima Darious, a Belgium-based activist who is in close contact with communities in the affected areas. “In general, there is extreme poverty in these villages, and people largely live off their land.”

She said houses were destroyed and entire livelihoods wiped out. In Kassab, an Armenian-populated town, “the apple, peach, and nectarine orchards were incinerated,” she said. “After the displacement, there’s nothing left for them.

“Across Latakia’s mountains, people depend on the harvest — they sell it to survive the whole year. They grow vegetables to feed themselves. Now that the crops have burned, it’s a devastating crisis. A disaster.”

By July 7 — just five days into the fires — SARD, a Syrian NGO assisting in the response, cited official estimates that about 5,000 people had been affected, with more than 1,120 displaced. Urgent needs include temporary shelter, clean drinking water, emergency food, hygiene and medical kits, respiratory aid, and psychosocial support.

Darious also warned of a looming hunger emergency. “We’re going to witness a level of hunger never seen before,” she said, adding that widespread damage to beehives — an essential part of local agriculture — has already led to soaring honey prices.

In addition to farming, many locals rely on seasonal tourism. “That source of income is gone too,” she said. “Who’s going to visit a burned forest or mountain? No tourism. No agriculture.”

Despite the scale of destruction, formal relief is limited. “There are no serious efforts to help the affected families — only individual initiatives,” Darious said. “Some local groups are trying to assist specific cases that are worse off than others.”

Compounding the tragedy, the fires were not merely a natural disaster. On July 3, the militant group Ansar Al-Sunnah claimed responsibility for deliberately starting the fires in the Qastal Maaf mountains.

This handout picture released by the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) shows firefighters battling forest fires in the Turkmen mountains in the al-Rabiah area of Syria's western Latakia's governorate on May 11, 2025. (AFP)

The group said in a statement its intent was to forcibly displace members of the Alawite sect — an ethno-religious community historically aligned with the Assad regime, although many of its members have lived in poverty for decades.

The arson is a chilling escalation in Syria’s ongoing instability, transforming environmental destruction into a weapon of sectarian violence. With villages burned, communities uprooted, and essential industries devastated, the damage extends far beyond ecological loss, deepening the schisms in Syrian society.

The attack followed a surge of violence in March in Syria’s coastal provinces, particularly in Latakia and Tartus, where clashes erupted between Assad loyalists and transitional opposition forces. The conflict quickly escalated into sectarian bloodshed.

Human rights observers reported summary executions and house raids in which attackers selected victims based on religious affiliation. Entire Alawite families were reportedly killed, underscoring the deliberate and systematic nature of the violence.

Since then, sectarian tensions have continued to spread. In other parts of the country, Christian communities have faced renewed violence and rising insecurity. High-profile incidents include a deadly bombing at Mar Elias Church in Damascus in June and a wave of arson attacks on Christian homes and churches in Suweida.

People and rescuers inspect the damage at the site of a reported suicide attack at the Saint Elias church in Damascus' Dwelaa area on June 22, 2025. (AFP)

In mid-July, the southern city of Suweida and surrounding areas endured intense clashes between Druze militias and Bedouin tribal fighters. Urban gun battles and retaliatory attacks left more than 300 dead in just two days.

Meanwhile in Latakia, as the smoke begins to clear, displaced families are returning to what little remains.

“People left their homes briefly due to the fire and then returned once it was contained,” said Marwan Al-Rez, head of the Mart volunteer team that supported civil defense and firefighting efforts. “Qastal Maaf was completely burned down. Its people were displaced again — some had only recently returned after the fall of the regime.”

Indeed, OCHA reported that many of the hardest-hit areas were predominantly communities of returning refugees. After the fires, returns have slowed significantly, with a noticeable decline even at the still-operational Kassab border crossing.

Qastal Maaf, a subdistrict of Latakia, comprises 19 localities and had a population close to 17,000 in 2004, according to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics. While the town itself is majority Sunni, surrounding villages are largely Alawite, highlighting the region’s complex sectarian makeup.

On July 9, the UN Satellite Centre released a fire damage assessment based on satellite imagery from a day earlier. The analysis identified burn scars in Qastal Maaf, Rabeea and Kassab — the first satellite overview of the extent of the fire.

Using WorldPop data and mapping the affected zones, UNOSAT estimated that approximately 5,500 people lived in or near the fire-affected areas. About 2,400 buildings may have been exposed to the flames.

UNOSAT stressed that these figures were preliminary and had not yet been validated through on-the-ground assessments at the time of publication.

The physical and environmental toll is staggering.

“Some agricultural lands in Kassab were completely burned,” Al-Rez said. “These were lush with trees — those were lost too.” Civil defense responders also suffered, with injuries including fractures and smoke inhalation.

The fires spread across more than 40 ignition points in the Jabal Al-Akrad and Jabal Turkmen regions, near the Turkish border, according to OCHA. This proximity triggered cross-border aerial firefighting efforts.

Efforts to contain the fires were hampered by high winds, soaring temperatures, and more than a decade of war-related damage.

“Excessive winds, high temperatures, and prolonged drought conditions have created a runaway disaster with no signs of slowing down,” said Abdulkarim Ekzayez, Syria country director for Action for Humanity, on July 6.

An emergency responder with the Syrian Civil Defense, known as the White Helmets, works to extinguish a wildfire near the town of Rabia, in Syria's Latakia countryside, Sunday, July 6, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Further complicating the mission were “14 years’ worth of unexploded remnants of war — landmines and bombs — that litter the country, threatening the lives of both emergency response crews and civilians evacuating,” Ekzayez added.

Action for Humanity sent teams to deliver water and fuel and to coordinate volunteers, who provided food and helped evacuate residents overcome by heat or smoke.

“The fire was spreading uncontrollably,” Al-Rez said. “It would leap across valleys and mountains, burning entire peaks in half an hour. Helicopters were the only way to reach many places.

“It was a terrifying and awe-inspiring sight,” he added, describing how entire mountainsides lit up in minutes.

Firefighters rest after battling a forest fire in the coastal Syrian province of Latakia on July 14, 2025. (AFP)

Alongside these organizations, the Red Crescent and Syrian American Medical Society were among several aid groups mobilized to assist.

Beyond the human toll, the fires have wrecked Syria’s ecosystems. “The consequences of the fires are severe for both humans and the environment,” Majd Suleiman, head of the Forestry Directorate, told local media.

Syria’s forests are home to aromatic trees used in industry and to shelter wildlife. They also play a role in regulating rainfall, humidity and temperatures.

Images and reports on social and traditional media show the broader ecological devastation — charred landscapes littered with dead deer, ducks, turtles and other animals.

As Syria begins the long process of recovery, the wildfires have laid bare the interconnected crises of conflict, climate and displacement, turning a seasonal hazard into a multifaceted catastrophe.