The very title ‘Minaret’ tells a lot about the novel. As we know a minaret is a tower from which the muezzin makes the call to prayer five times a day. It needs to be stressed at the outset that this is not a didactic novel. But it does make an impact and prods a person to think about the place of faith in life. Maybe the author did not intend or use the ‘minaret’ as a symbolism, but it does make a strong appeal and invite one to all that a mosque stands for. In this book, it is the mosque with its religious training classes and those who attend them, including Najwa, that makes the difference in their lives.

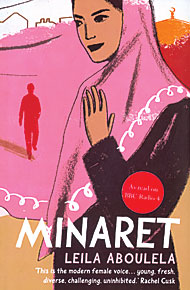

“I look up and see the minaret of Regent’s Park mosque above the trees…,” says Najwa as she is on her way to a flat for interview as housemaid. ‘Minaret’ is a story that will touch many readers’ hearts. The characters come alive; Najwa herself is not conspicuous, even though she is the narrator. It is to the credit of the author — Leila Aboulela — that the person who projects other characters in the novel is also remembered. The story, as all good stories, has a beginning, middle and an Indian movie-style end which, unlike the Indian films, is not melodramatic, but is effective and strikes one as a fabric that was being woven all along. Leila, who grew up in Khartoum, was the first winner of the Caine Prize for African Writing. She is also the author of “The Translator,” a novel, which has been long-listed for the Orange Prize, and “Coloured Lights,” a book of short stories.

The author writes in a forthright style. No mincing of words, no long sentences. “I’ve come down in the world. I’ve slid to a place where the ceiling is low and there isn’t much room to move. Most of the time I’m used to it. Most of the time I’m good. I accept my sentence and do not brood or look back,” are the opening sentences as Najwa tells her story.

The very first sentence: “I’ve come down in the world,” makes the reader sit up and go on reading further to find out why and how far down Najwa has slid. The style, at times, is pictorial. For example, the lines describing her driving home with her brother Omar from a disco early in the morning as the muezzin calls to prayer might well have been painted with a brush. “We heard the dawn azan (call to prayer) as we turned into our house. The guard got up from where he was sleeping on the ground and opened the gate for us…. The servants stirred and, from the back of the house, I heard the sound of gushing water, someone spitting, a sneeze, the shuffle of slippers on the cement floor of their quarters. A light bulb came on. They were getting ready to pray…” Najwa dreamt dreams shaped by pop songs and American films. Studying at Khartoum University, she led a sheltered, cozy life as the daughter of a father who was close to the President of Sudan — attending parties, visiting European cities on holidays, shopping at expensive shops, with little time for prayers, or fasting in Ramadan. “How could anyone fast in London? It would spoil all the fun.”

Her father was planning to have his own private jet. “Three more years at the maximum — I’ve got it all planned,” he said during a family picnic. But everything started to fall apart that very night when they returned home late. A coup had taken place, and her father was taken away, never to be seen again — executed while the family was in London, where it had fled.

There, she never let it be known who she was. She always lied that she was Eritrean or Somali. “… Our succession of Ethiopian maids, houseboys, or gardener — I must have been close to them, absorbing their ways, so that now, years later and on another continent, I am one of them.” After all the vicissitudes — father’s execution, exile to London, mother’s illness and subsequent death, brother Omar’s spending time in jail on a drugs charge, failed relationship with staunch communist Anwar, the Khartoum University colleague she wanted to marry, but couldn’t because he refused, forced not to marry the religious-minded Tamer, her employer’s brother, who wanted her as his wife — she finds peace and guidance in religion. As she tells Omar during a visit to prison: “We weren’t brought up in a religious way, neither of us. We weren’t even friends in Khartoum with people who were religious …. If Baba and Mama had prayed, if you and I had prayed, all of this wouldn’t have happened to us.” What she tells Tamer during a stroll in the park with her employer’s daughter: “We never get lost because we can see the minaret of the mosque and head home towards it,” is true as a guide to life’s real goals and destinations.