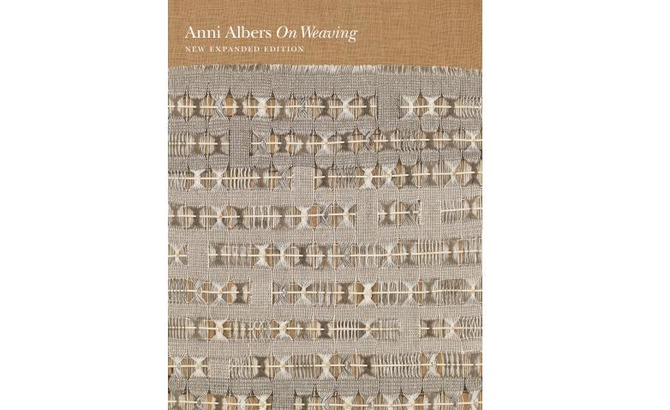

One can only rejoice at the release of a new, expanded edition of one of the world’s best books on weaving. “On Weaving” is an absolute masterpiece written by Anni Albers, one of the most talented and creative artists of the 20th century. Printed several times since its first publication in 1965, this new version features full-cover photographs instead of the book’s original black-and-white illustrations, as well as an afterword by Nicholas Fox Weber, executive director of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and essays by Manuel Cirauqui and T’ai Smith.

Weber writes in the afterword that Albers “took the art of textiles into realms that are glorious guideposts for all people for all time.” Albers revolutionized the way people looked at textiles, she also gave weavers and designers whose inspiration was stifled a breath of fresh air. She opened new channels of creativity, suggesting unforeseen possibilities, new ways of combining visual and structural work in thread, art and design.

“How do we choose our specific material, our means of communication? Accidentally, something speaks to us, a sound, touch, hardness or softness, it catches us and asks us to be formed. We are finding our language and as we go along we learn to obey its rules and its limits,” Albers once said.

And indeed, Albers found her medium, weaving, by accident. In 1922, at the age of 23, Albers was accepted into Bauhaus, a pioneering school in Germany whose mission was to teach the role of functional art and design to everyone, regardless of wealth and class. Bauhaus provided courses in various specialties, such as woodworking, metal, wall painting and glass. Most women at the time chose to enter the weaving workshop whereas Albers preferred to study the art of glasswork. However, Walter Gropius, who founded Bauhaus, believed that it was not advisable that women work in the heavy crafts areas, such as carpentry and he said: “For this reason, a women’s section has been formed at the Bauhaus (School), which works particularly with textiles, bookbinding and pottery.”

Ambitious and eager to know more about the history of textiles, Albers visited ethnological museums in Berlin and Munich and read “Les Tissus Indiens du Vieux Perou” by Marguerite and Raoul d’Harcourt, which introduced her to the ancient textile art of Peru. She would eventually consider the Peruvian weavers as “her greatest teachers” because nearly all the existing methods of weaving had been used in ancient Peru.

During her early years as an artist, Albers was profoundly influenced by Paul Klee who repeatedly insisted that the ultimate form of an artistic work was not as significant as the process leading to it. Klee also introduced her to his use of formal experimentation and graffiti-like markings, which he believed could nurture the subconscious. Albers adopted this concept and integrated it into her abstract tapestries.

This book takes the reader on a journey of discovery of an ancient craft, one that has remains essentially unchanged to this day. The book’s first chapter, “Weaving, Hand” is in fact the entry about weaving that Albers wrote for Encyclopedia Britannica: “One of the most ancient crafts, hand weaving is a method of forming a pliable plane of threads by interlacing them rectangularly. Invented in a pre-ceramic age, it has remained essentially unchanged to this day. Even the final machinery has not changed the basic principle of weaving.”

Weaving is one of the oldest surviving crafts in the world and goes back to Neolithic times, about 12,000 years ago. “Beginnings are usually more interesting than elaborations and endings. Beginning means explorations, selections, development, a potent vitality not yet limited, not circumscribed by the tried and traditional,” wrote Albers.

The artist used to take her students back in time to understand how it all began. The hides of animals are probably the closest prototype to fabrics. They are flat and versatile and can be used for many purposes. They can protect us from the weather and also shelter us as roofs and walls. Perhaps it all began when someone had the idea of adding a flexible twig to fasten the hides together. This manner of using both a stiff and a soft material was found in the 5,000-year-old mummy wrappings excavated in Paracas, Peru.

The wrappings extracted from the tombs were like “rushes tied together in the manner of twining… stiff materials were connected by means of a softer one to form a mat pliable in one direction, stiff in another,” wrote Albers.

These rushes are closer to basketry than fabrics. In fact baskets made using a similar technique were found in the same burial site. Twining is a method that appears to have evolved into weaving and this, according to Albers, might explain one of the origins of textile techniques.

Knotting, netting and looping resemble twining. Crocheting and knitting are said to have been invented by the Arabs. The oldest specimens have been located in Egyptian tombs from the seventh or eighth century.

Tapestry weaving is a form of weaving that dates back to the earliest beginnings of thread interlacing. One of the earliest pictorial works was found in a tomb located in northern Peru. Along with cave paintings, threads were the earliest transmitters of meaning, according to the book.

Albers developed “pictorial weaving” between the 1930s and 1960s. Her woven pictures are unique works of art in which colors, sounds, abstract forms and pictures are embedded in the fabric. Thanks to a unique and sophisticated technique combining history and innovation, an unbridled imagination and unrestrained energy, Albers weaved masterpieces. Her tapestries celebrate not only the wonder and dynamism of fiber, but also the beauty and mystery of life itself.

Book Review: Unraveling the history of weaving

Book Review: Unraveling the history of weaving

What We Are Reading Today: The Aesthetic Cold War by Peter J. Kalliney

How did superpower competition and the cold war affect writers in the decolonizing world? In “The Aesthetic Cold War,” Peter Kalliney explores the various ways that rival states used cultural diplomacy and the political police to influence writers.

In response, many writers from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean — such as Chinua Achebe, Mulk Raj Anand, Eileen Chang, C.L.R. James, Alex La Guma, Doris Lessing, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, and Wole Soyinka — carved out a vibrant conceptual space of aesthetic nonalignment, imagining a different and freer future for their work.

What We Are Reading Today: Ocean

Authors: David Attenborough, Colin Butfield

Drawing a course across David Attenborough’s own lifetime, Ocean takes readers through eight unique ocean habitats, through countless intriguing species, and through the most astounding discoveries of the last 100 years, to a future vision of a fully restored marine world, even richer and more spectacular than we could possibly hope.

Ocean reveals the past, present and potential future of our blue planet.

What We Are Reading Today: ‘How to Change a Memory’ by Steve Ramirez

As a graduate student at MIT, Steve Ramirez successfully created false memories in the lab. Now, as a neuroscientist working at the frontiers of brain science, he foresees a future where we can replace our negative memories with positive ones.

“In How to Change a Memory,” Ramirez draws on his own memories—of friendship, family, loss, and recovery—to reveal how memory can be turned on and off like a switch, edited, and even constructed from nothing.

A future in which we can change our memories of the past may seem improbable, but in fact, the everyday act of remembering is one of transformation.

Book Review: ‘The Brain’ by Alison George

Imagine having a manual for the brain, the remarkable, mysterious machine that powers thoughts, dreams, and creativity, and stands as the force behind human civilization, setting our species apart from all others on Earth.

“The Brain: Everything You Need to Know” by Alison George, published by New Scientist, breaks down consciousness, memory, intelligence, and even why we dream, in a way that is light and easy to follow. It avoids scientific jargon, making it a good choice for readers who are curious about the brain but don’t want to get lost in technical details.

Along the way, the book asks a fundamental question: How can we understand, and even improve, the way our minds function?

The book argues that the brain is far more complex than we tend to assume. Many of its processes happen outside of conscious awareness, and even the ways we make decisions, form memories, or dream are shaped by forces we barely notice.

Understanding the brain, the book suggests, requires accepting that much of what drives us happens invisibly.

One chapter that stands out takes a closer look at the unconscious mind, described as the brain’s “unsung hero.” It’s where habits live and decisions form long before they reach awareness. Everyday actions like walking, typing, or even choosing what to eat are often driven by this autopilot system. The book explores how deeply the unconscious shapes behavior, challenging the idea that we are always fully in control of our actions.

Some of the chapters are short and punchy, which keeps the pace moving, but this also means the book doesn’t spend enough time exploring some of the topics. It can feel more like an introduction to neuroscience than a true exploration of it. For readers seeking a light, engaging overview of the mind’s mysteries, this approach may work well. Those hoping for deeper engagement, however, might be left wanting more.