WASHINGTON: The West — and the Western media especially — has tended to see Saudi Arabian women mostly as victims, passive players in a deeply patriarchal culture.

That view has been slowly changing. As the driving ban lifts this June, Saudi women are being perceived not as victims but as standing up for their rights.

Hend Al-Mansour, a leading figure in the Saudi women’s movement, is one of the most widely recognized Saudi women artists. She has been on a quest to reclaim, through her art, the story of women in the Arab world.

“In the first few years (of my shows), I found myself more or less educating people, trying to help them understand the basic thing, that women in the Arab world are not passive,” she said. “Later, the audience was more understanding. Especially now, as the Saudis are on the front pages, people understand more.

“People are very curious. Gradually, they’re getting it. It’s baby steps.”

Al-Mansour came to the US 21 years ago as a physician, then gave up medicine for art. Her work received the juror’s award at the Contemporary Islamic Art exhibition in Riyadh in 2012 and she received the Jerome fellowship in printmaking.

One of her prints was recently on the cover of a report for the Center for Women’s Global Leadership, a nod to Al-Mansour’s importance among Saudi Arabian feminists. The report lists 20 instances of activism in three different waves by Saudi women, starting from the historic demonstration against the driving ban on Nov. 6, 1990.

In an extraordinarily open conversation, Al-Mansour talked with Arab News about leaving medicine for art, the status of women in Saudi Arabia, and the changing view of Arab women in the West.

How has the view of women in the Arab world changed, especially from the West?

Especially in the West, there is a broad blanket, and it covers all women. But the Arab world is not homogeneous. In the 1970s, when I visited Beirut, it was normal for women and girls to wear miniskirts. In Saudi Arabia, men and women have been assigned well-defined, separate spaces. I studied in Egypt (attending medical school there). There women could get a wide range of education. They could be engineers, doctors.

In the late 80s and 90s, a wave of conservatism came over the Middle East. When I went back to Saudi Arabia in the 2000s, I could see black gloves, and I was surprised.

When I first came (to the US) they didn’t differentiate: A Pakistani, Iranian and Arab were the same thing. After the Arab Spring, they began to understand there are differences.

More importantly, they understand women are not passive in the Arab world. Women in the Middle East have conviction. If they put hijab on, they believe that this is part of their identity, religion and respect for their bodies. If they don’t put it on, they have conviction about that, too. They are active in whatever they’re doing. They are passionate.

I have often wondered, looking at photographs of the old Middle East, what would cause women to willingly give up some of their freedom?

I don’t understand either. When I was in Saudi Arabia, my friends were mostly unveiled. When I went back, my friends were all veiled. It’s a social phenomenon, but I don’t think religion is the cause. The religion is the result (of the same wave that results in women putting on the veil).

I put on hijab in Egypt for more than a year. It was a more of a rebellious act. I was catching the beginning of the wave.

What made you take it off?

I felt like a hypocrite. My behavior wasn’t that of a pious woman.

How do you explain the influence of religion in Saudi Arabia to Americans?

In Saudi Arabia (some believe that) the morality of the community depends on how the women dress and behave. The duty of the women is to keep society straight. Men’s job is to guard women.

It’s complex. Men are not off the hook. The whole community has roles, but they’re not natural. There is a concept in Saudi Arabia that women have half brains. That’s why I went to medical school, to prove that wrong. Now, there is a deviation from all that baggage, as Saudi Arabia becomes less isolated. Women are being recognized as whole humans.

What are some lost stories of Saudi Arabia?

When I was in Saudi Arabia, I learned the Western art. I admired Leonardo da Vinci. But there were beautiful local practices, like henna, I didn’t recognize. When my mother was a young woman, she thought henna was something backwards. … But each local, beautiful pattern has a name. We have lost it now. …I (found) eight of the patterns, and created an image of them. I made a series of prints from those. I also printed around them a folktale from the same period of time: Green in Souk, Red in Mother.

Another thing that we lost is the native architecture. When I was a child, under 10, there was a totally different landscape, of mud houses and narrow streets. The narrow streets keep the shadow in the street, and women can move in between their houses without having to veil. Even in the neighborhood, they could go from one house to another.

Does your mother like what you’re doing now?

She was really excited when I became a doctor, and mad at me when I left medicine, though she thinks I am a good artist. … She didn’t go to school when she was young, because there weren’t any schools. She studied with me.

What people should recognize is that women in Saudi Arabia are working harder than other women to make progress, to be in that place. I remember a story a woman told me of what her father did when he saw her holding a pencil – just holding a pencil. That was a great sin, and he hit her.

What led you to give up being a doctor to become an artist?

I wanted freedom of expression and freedom to be myself. It was really hard. When I realized how our conception of art in the Arab world was limited to Western art, the whole question of identity came to the fore.

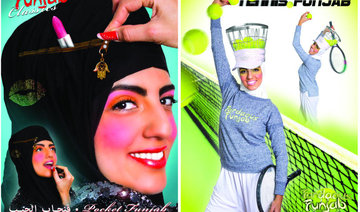

Mostly what I like to do now are installations. I take rolls of paper or rolls of fabric and hang them on a skeleton. I build those spaces, borrowing the shapes of tents and mosques. My latest is called the “Pink House of God.” It’s about a Saudi woman who lives in Minnesota and includes a design made by Bedouin women. This design is intermingled with Tinkerbell. Tinkerbell was important to the woman I interviewed, because Tinkerbell is independent and could manage things.

There is a prayer rug on the floor. I want to show we can identify with Arab women. I put women into these shrines. This is more of a message to the Arab or Islamic audience.