LONDON: Ali Imdad is drizzling almond oil into a delicious-smelling dessert ready for the after-work crowd that will pile into Milk Cafe later to enjoy a slice of cake infused with flavours from across the Muslim world.

Like Imdad, who was born and raised in the UK, the backbone of each recipe is British, but the essence of his cakes comes from the East, bringing the culinary traditions of his Pakistani heritage and other countries across the Islamic world to the trendy London borough of Hackney where, he hopes, they will inspire a different dialogue about what it means to be Muslim.

Imdad, 30, who was runner-up on the popular Great British Bake Off TV show, says he wants to encourage a “more wholesome” perception of Islam in the UK through his pop-up cafe, which is entering the final phase of a successful four-week run.

“Muslims historically haven’t just focused on religion,” says Imdad, citing the impact of Islamic culture on the arts, sciences and literature as well as cuisine. “Food has been integral to Muslims since the dawn of Islam, but people are surprised to hear that it was Muslims who brought orange juice here.”

Growing up in the “very Asian community” of the Alum Rock suburb of Birmingham, Imdad never considered his Muslim identity. “I didn’t really think about what being Muslim meant, it was just something I was.” Never having reason to question his place in society, he felt “just as British as the next person.”

But after 9/11 he noticed a shift. On the bus, he would overhear people discussing his religion and on more than one occasion he was asked to explain the Taliban’s motives. “For the first time I felt like the other.”

In the charged political climate since Britain’s decision to leave the European Union, Imdad said that he has encountered more instances of Islamophobia, from racial slurs to ripping off women’s hijabs, than he cares to remember.

“We’re on dangerous territory,” he said, concerned by the “increasing acceptance” toward anti-Islamic sentiment, popularised by certain prominent politicians and academics who are “welcoming far-right hate speech.”

When an anonymous letter was circulated last March naming April 3 as “Punish a Muslim Day” and calling for attacks against Muslims, he decided to act. He posted a tweet on social media saying that although ”hatred doesn’t scare me” that ”my mum is sitting reading the Qur’an and praying for safety ... That she feels she has to pray to stay safe just for being a Muslim. When did we go back to the 1930s again?”

He said that he felt a responsibility to “call them out.” After the Manchester bombing in May last year he noticed a surge in Islamophobic comments over social media. “As a Muslim you need to defend other Muslims,” he said, explaining that for him as a baker, it was about creating an environment where people could discover the culinary culture of Islam.

“It’s a more subtle approach toward introducing people to the different cultures of Islam, they can come and discuss the religion, or just enjoy the food and see, through my desserts, how Muslims have contributed to world cuisine.”

“We’re real foodies,” he says, slicing a tray of brownies into thick wedges for his most popular recipe, which infuses dates, figs and chocolate into the popular English pudding. His menu, which also stars a delectable Moroccan-inspired orange and pomegranate drizzle cake and a Pakistani-themed chai-spiced chocolate sphere, aims to reflect the diversity of the Muslim world.

“I want to remind people that there isn’t a single Muslim culture; there are cultures within the Muslim field and my desserts aren’t just Muslim desserts, they’re from Malaysia, Morocco, Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, Egypt and beyond.”

There’s only so much that can by achieved with a menu of cakes — however inspired the recipes — and Imdad is the first to acknowledge this, but he feels that an “accessible”, “grassroots” approach is what’s lacking in efforts to combat the rising tide of Islamophobia in Britain.

“There are plenty of people talking on our behalf at the political level, but not everybody is interested in politics … this is for people who want to talk about Islam in terms of the history, or the food, or the culture, rather than discussing terrorism, bombs or wars.”

His latest recipe, which is emitting a mouthwatering perfume from the bowl as we speak, was dreamed up on the train here as he sifted through the memories of a visit to Egypt 10 years ago. Although it is the first time he has made it, he is sure that the flavours — almond cake infused with cinnamon syrup and a vanilla and ginger gelato, will work and conjure up his experience of Egypt for his customers.

Imdad said that it is a subtle, but powerful platform: “Everyone’s interested in food and what better way to bring everyone together?” Back at home Alum Rock, he said that he is conscious of the deepening divisions in British society.

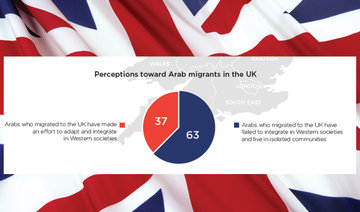

“When I was younger there used to be quite a few white families living there, but now, 20 years later, they’re all gone, I don’t remember the last time I saw a white face there.”

Much has been said at the political level about addressing the issues surrounding the integration of minority communities in the UK, but the starting point for change, Imdad said, is conversation. “We can’t keep living separate but together … dialogue is the only way to bridge that divide, ideally over cake.”

- Milk Cafe will open at Bake Street cafe in London, from 5.30pm to 11pm until May 13. Reservations can be made over social media or by emailing [email protected]