ASSAMAKA, Niger: From this isolated frontier post deep in the sands of the Sahara, the expelled migrants can be seen coming over the horizon by the hundreds. They look like specks in the distance, trudging miserably across some of the world's most unforgiving terrain in the blistering sun.

They are the ones who made it out alive.

Here in the desert, Algeria has abandoned more than 13,000 people in the past 14 months, including pregnant women and children, stranding them without food or water and forcing them to walk, sometimes at gunpoint, under temperatures of up to 48 degrees Celsius (118 degrees Fahrenheit).

In Niger, where the majority head, the lucky ones limp across a desolate 15-kilometer (9-mile) no-man's-land to Assamaka, less a town than a collection of unsteady buildings sinking into drifts of sand. Others, disoriented and dehydrated, wander for days before a UN rescue squad can find them. Untold numbers perish along the way; nearly all the more than two dozen survivors interviewed by The Associated Press told of people in their groups who simply could not go on and vanished into the Sahara.

"Women were lying dead, men..... Other people got missing in the desert because they didn't know the way," said Janet Kamara, who was pregnant at the time. "Everybody was just on their own."

Her body still aches from the dead baby she gave birth to during the trek and left behind in the Sahara, buried in a shallow grave in the molten sand. Blood streaked her legs for days afterward, and weeks later, her ankles are still swollen. Now in Arlit, Niger, she is reeling from the time she spent in what she calls "the wilderness," sleeping in the sand.

Quietly, in a voice almost devoid of feeling, she recalled at least two nights in the open before her group was finally rescued, but said she lost track of time.

"I lost my son, my child," said Kamara, a Liberian who ran her own home business selling drinks and food in Algeria and was expelled in May.

Another woman in her early twenties, who was expelled at the same time, also went into labor, she said. That baby didn't make it either.

Algeria's mass expulsions have picked up since October 2017, as the European Union renewed pressure on North African countries to head off migrants going north to Europe via the Mediterranean Sea or the barrier fences with Spain. These migrants from across sub-Saharan Africa — Mali, the Gambia, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Niger and more — are part of the mass migration toward Europe, some fleeing violence, others just hoping to make a living.

A European Union spokesperson said the EU was aware of what Algeria was doing, but that "sovereign countries" can expel migrants as long as they comply with international law. Unlike Niger, Algeria takes none of the EU money intended to help with the migration crisis, although it did receive $111.3 million in aid from Europe between 2014 and 2017.

Algeria provides no figures for the expulsions. But the number of people crossing on foot to Niger has been increasing steadily since the International Organization for Migration started counting in May 2017, when 135 people were dropped at the crossing, to as high as 2,888 in April 2018. In all, according to the IOM, a total of 11,276 men, women and children survived the march.

At least another 2,500 were forced on a similar trek this year through the Sahara into neighboring Mali, with an unknown number succumbing along the way.

The migrants the AP talked to described being rounded up hundreds at a time, crammed into open trucks headed southward for six to eight hours to what is known as Point Zero, then dropped in the desert and pointed in the direction of Niger. They are told to walk, sometimes at gunpoint. In early June, 217 men, women and children were dropped well before reaching Point Zero, fully 30 kilometers (18 miles) from the nearest source of water, according to the IOM.

Within seconds of setting foot on the sand, the heat pierces even the thickest shoes. Sweat dries upon the first touch of air, providing little relief from the beating sun overhead. Each inhalation is like breathing in an oven.

But there is no turning back.

"There were people who couldn't take it. They sat down and we left them. They were suffering too much," said Aliou Kande, an 18-year-old from Senegal.

Kande said nearly a dozen people simply gave up, collapsing in the sand. His group of 1,000 got lost and wandered from 8 a.m. until 7 p.m., he said. He never saw the missing people again. The word he returned to, over and over, was "suffering."

Kande said the Algerian police stole everything he had earned when he was first detained — 40,000 dinars ($340) and a Samsung cell phone.

"They tossed us into the desert, without our telephones, without money. I couldn't even describe it to you," he said, still livid at the memory.

The migrants' accounts are confirmed by multiple videos collected by the AP over months, which show hundreds of people stumbling away from lines of trucks and buses, spreading wider and wider through the desert. Two migrants told the AP gendarmes fired on the groups to force them to walk, and multiple videos seen by the AP showed armed, uniformed men standing guard near the trucks.

"They bring you to the end of Algeria, to the end in the middle of the desert, and they show you that this is Niger," said Tamba Dennis, another Liberian who was in Algeria on an expired work visa. "If you can't bring water, some people die on the road." He said not everyone in his group made it, but couldn't say how many fell behind.

Ju Dennis, another Liberian who is not related to Tamba, filmed his deportation with a cell phone he kept hidden on his body. It shows people crammed on the floor of an open truck, vainly trying to shade their bodies from the sun and hide from the gendarmes. He narrated every step of the way in a hushed voice.

Even as he filmed, Ju Dennis knew what he wanted to tell the world what was happening.

"You're facing deportation in Algeria — there is no mercy," he said. "I want to expose them now...We are here, and we saw what they did. And we got proof."

Algerian authorities refused to comment on the allegations raised by the AP. Algeria has denied criticism from the IOM and other organizations that it is committing human rights abuses by abandoning migrants in the desert, calling the allegations a "malicious campaign" intended to inflame neighboring countries.

Along with the migrants who make their way from Algeria to Niger on foot, thousands more Nigerien migrants are expelled directly home in convoys of trucks and buses. That's because of a 2015 agreement between Niger and Algeria to deal with Nigeriens living illegally in their neighbor to the north.

Even then, there are reports of deaths, including one mother whose body was found inside the jammed bus at the end of the 450-kilometer (280-mile) journey from the border. Her two children, both sick with tuberculosis, were taken into custody, according to both the IOM and Ibrahim Diallo, a local journalist and activist.

The number of migrants sent home in convoys — nearly all of them Nigerien — has also shot up, to at least 14,446 since August 2017, compared with 9,290 for all of 2016.

The journey from Algeria to Niger is essentially the reverse of the path many in Africa took north — expecting work in Algeria or Libya or hoping to make it to Europe. They bumped across the desert in Toyota Hilux pickups, 15 to 20 in the flatbed, grasping gnarled sticks for balance and praying the jugs of water they sat upon would last the trip.

The number of migrants going to Algeria is increasing as an unintended side effect of Europe's successful blocking of the Libyan crossing, said Camille Le Coz, an analyst at the Migration Policy Institute in Brussels.

But people die going both ways; the Sahara is a swift killer that leaves little evidence behind. The arid heat shrivels bodies, and blowing sand envelops the remains. The IOM has estimated that for every migrant known to have died crossing the Mediterranean, as many as two are lost in the desert — potentially upwards of 30,000 people since 2014.

The vast flow of migrants puts an enormous strain on all the points along the route. The first stop south is Assamaka, the only official border post in the 950-kilometer (590 mile) border Algeria shares with Niger.

Even in Assamaka, there are just two water wells — one that pumps only at night and the other, dating to French colonial times, that gives rusty water. The needs of each wave of expelled migrants overwhelm the village — food, water, medicine.

"They come by the thousands....I've never seen anything like it," said Alhoussan Adouwal, an IOM official who has taken up residence in the village to send out the alert when a new group arrives. He then tries to arrange rescue for those still in the desert. "It's a catastrophe."

In Assamaka, the migrants settle into a depression in the dunes behind the border post until the IOM can get enough buses to fetch them. The IOM offers them a choice: Register with IOM to return eventually to their home countries or fend for themselves at the border.

Some decide to take their chances on another trip north, moving to The Dune, an otherworldly open-air market a few kilometers away, where macaroni and gasoline from Algeria are sold out of the back of pickups and donkey carts. From there, they will try again to return to Algeria, in hopes of regaining the lives and jobs they left behind. Trucks are leaving all the time, and they take their fare in Algerian dinars.

The rest will leave by bus for the town of Arlit, about 6 hours to the south through soft sand.

In Arlit, a sweltering transit center designed for a few hundred people lately has held upwards of 1,000 at a time for weeks on end.

"Our geographical position is such that today, we are directly in the path of all the expulsions of migrants," said Arlit Mayor Abdourahman Mawli. Mawli said he had heard of deaths along the way from the migrants and also from the IOM. Others, he said, simply turned right round and tried to return to Algeria.

"So it becomes an endless cycle," he said wearily.

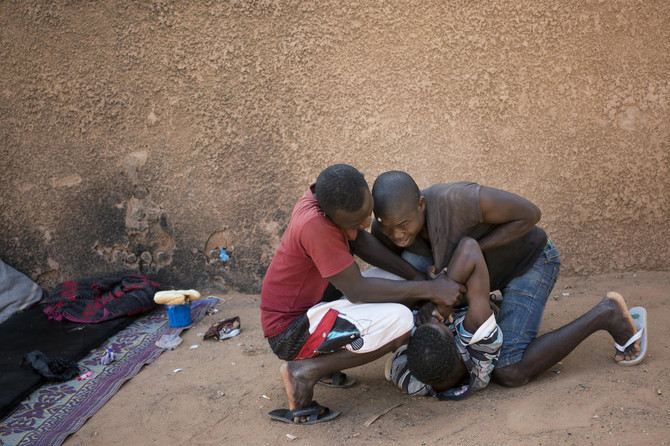

One man at the center with scars on his hands and arms was so traumatized that he never spoke and didn't leave. The other migrants assumed he had endured the unspeakable in Algeria, a place where many said they had been robbed and beaten by authorities. Despite knowing nothing about him, they washed and dressed him tenderly in clean clothes, and laid out food so he could eat. He embarked on an endless loop of the yard in the midday sun.

With no name, no confirmed nationality and no one to claim him, the man had been in Arlit for more than a month. Nearly all of the rest would continue south mostly off-road to Agadez, the Nigerien city that has been a crossroads for African trade and migration for generations. Ultimately, they will return to their home countries on IOM-sponsored flights.

In Agadez, the IOM camps are also filling up with those expelled from Algeria. Both they and the mayor of Agadez are growing increasingly impatient with their fate.

"We want to keep our little bit of tranquility," said the mayor, Rhissa Feltou. "Our hospitality is a threat to us."

Even as these migrants move south, they cross paths with some who are making the trip north through Agadez.

Every Monday evening, dozens of pickup trucks filled with the hopeful pass through a military checkpoint at the edge of the city. They are fully loaded with water and people gripping sticks, their eyes firmly fixed on the future.

Walk or die: Algeria abandons 13,000 migrants in the Sahara

Walk or die: Algeria abandons 13,000 migrants in the Sahara

- The expelled migrants can be seen coming over the horizon by the hundreds, appearing at first as specks in the distance under temperatures of up to 48 degrees Celsius

- Algeria's mass expulsions have picked up since October 2017, as the European Union renewed pressure on North African countries to head off migrants going north to Europe via the Mediterranean Sea or the barrier fences with Spain

UN’s top anti-racism body calls for immediate Gaza aid access

- Civilian population ‘at imminent risk of famine, disease and death,’ statement warns

- Israel has blocked humanitarian aid entering Gaza since March in bid to ‘pressurize Hamas’

NEW YORK CITY: The UN’s top anti-racism body has called for immediate humanitarian access to Gaza in a bid to avoid “catastrophic consequences” for its civilian population.

The statement by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination — comprised of independent experts — came hours after the World Central Kitchen charity said it was forced to end operations in Gaza due to a lack of food.

It also follows a commitment by Israel to “conquer” almost all of the enclave, as well as disputes involving Israel, the UN and US over the appropriate way to deliver humanitarian aid to Palestinians there.

The CERD committee is convening in Geneva for its latest session, ending today.

Gaza’s civilian population, “especially vulnerable groups such as children, women, the elderly and persons with disabilities,” are “at imminent risk of famine, disease and death,” the committee said.

The warning follows an earlier appeal by the World Food Programme, the UN’s food agency, which said that almost all food aid operations in Gaza had collapsed.

Late last month, the agency announced that the entirety of its food reserves in the enclave had been depleted.

Since March, Israel has blocked humanitarian aid into Gaza in a bid to build pressure on Hamas, which still holds Israeli hostages.

Tom Fletcher, the UN’s emergency relief coordinator, said last week: “Two months ago, the Israeli authorities took a deliberate decision to block all aid to Gaza and halt our efforts to save survivors of their military offensive.

“They have been bracingly honest that this policy is to pressurize Hamas.”

Expanded military operations by Israel in Gaza over the past two months “have dramatically worsened the humanitarian crisis and severely endangered the civilian population,” Friday’s CERD statement said.

The committee called on Israel to “lift all barriers to humanitarian access, allow the immediate and unimpeded entry of humanitarian aid, and cease all actions obstructing the provision of essential services to the civilian population in Gaza.”

The statement also highlighted worsening conditions across the Occupied Palestinian Territories, including in East Jerusalem, where Israel closed six UNRWA schools this week.

Philippe Lazzarini, the Palestinian refugee agency’s chief, reacted with fury over the move, describing it as an “assault on children.”

The CERD statement called on all UN states to “cooperate to bring an end to the violations that are taking place and to prevent war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, including by ceasing any military assistance.”

UN committee warns of ‘another Nakba’ in Palestinian territories

- During the 1948 war, around 760,000 Palestinians fled or were driven from their homes in what became known as “the Nakba”

GENEVA: The world could be witnessing “another Nakba” expulsion of Palestinians, a United Nations committee warned Friday, accusing Israel of “ethnic cleansing” and saying it was inflicting “unimaginable suffering” on Palestinians.

For Palestinians, any forced displacement evokes memories of the “Nakba,” or catastrophe — the mass displacement in the war that accompanied to Israel’s creation in 1948.

“Israel continues to inflict unimaginable suffering on the people living under its occupation, whilst rapidly expanding confiscation of land as part of its wider colonial aspirations,” warned a UN committee tasked with probing Israeli practices affecting Palestinian rights.

“What we are witnessing could very well be another Nakba,” it said, after concluding an annual mission to Amman.

During the 1948 war, around 760,000 Palestinians fled or were driven from their homes in what became known as “the Nakba.”

The descendants of some 160,000 Palestinians who managed to remain in what became Israel presently make about 20 percent of its population.

The UN Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories was established by the UN General Assembly in December 1968.

The committee is currently composed of the Sri Lankan, Malaysian and Senegalese ambassadors to the UN in New York.

“What the world is witnessing could very well be a second Nakba. The goal of wider colonial expansion is clearly the priority of the government of Israel,” they said in their report.

“Security operations are used as a smokescreen for rapid land grabbing, mass displacement, dispossession, demolitions, forced evictions and ethnic cleansing, in order to replace the Palestinian communities with Jewish settlers.”

Iran, US to resume nuclear talks on Sunday after postponement

- Fourth round of indirect negotiations, initially set for May 3 in Rome, postponed due to ‘logistical reasons’

DUBAI: Iran has agreed to hold a fourth round of nuclear talks with the United States on Sunday in Oman, Foreign Minister Abbas Aragchi said on Friday, adding that the negotiations were advancing.

US President Donald Trump, who withdrew Washington from a 2015 deal between Tehran and world powers meant to curb its nuclear activity, has threatened to bomb Iran if no new deal is reached to resolve the long unresolved dispute.

Western countries say Iran’s nuclear program, which Tehran accelerated after the US walkout from the now moribund 2015 accord, is geared toward producing weapons, whereas Iran insists it is purely for civilian purposes.

“The negotiations are moving forward, and naturally, the further we go, the more consultations and reviews are needed,” Aragchi said in remarks carried by Iranian state media.

“The delegations require more time to examine the issues that are raised. But what is important is that we are on a forward-moving path and gradually entering into the details.”

The fourth round of indirect negotiations, initially scheduled for May 3 in Rome, was postponed, with mediator Oman citing “logistical reasons.”

Aragchi said a planned visit to Qatar and Saudi Arabia on Saturday was in line with “continuous consultations” with neighboring countries to “address their concerns and mutual interests” about the nuclear issue.

No milk, no diapers: US aid cuts hit Syrian refugees in Lebanon

- Merhi and her family are among the millions of people affected by Trump’s decision to freeze USAID funding to humanitarian programs

- Since the freeze, the UNHCR and WFP have had to limit the amount of aid they provide

BEIRUT: Amal Al-Merhi’s twin 10-month-old daughters often go without milk or diapers.

She feeds them a mix of cornstarch and water, because milk is too expensive. Instead of diapers, Merhi ties plastic bags around her babies’ waists.

The effect of their poverty is clear, she said.

“If you see one of the twins, you would not believe she is 10-months-old,” Merhi said in a phone interview. “She is so small and soft.”

The 20-year-old Syrian mother lives in a tent with her family of five in an informal camp in Bar Elias in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley.

She fled Syria’s civil war in 2013 and has been relying on cash assistance from the United Nations refugee agency UNHCR to get by.

But that has ended.

Merhi and her family are among the millions of people affected by US President Donald Trump’s decision to freeze USAID funding to humanitarian programs.

Since the freeze, the UNHCR and the World Food Program (WFP) have had to limit the amount of aid they provide to some of the world’s most vulnerable people in countries from Lebanon to Chad and Ukraine.

In February, the WFP was forced to cut the number of Syrian refugees receiving cash assistance to 660,000 from 830,000, meaning the organization is reaching 76 percent of the people it planned to target, a spokesperson said.

Meanwhile, the WFP’s shock responsive safety net that supports Lebanese citizens cut its beneficiaries to 40,000 from 162,000 people, the spokesperson added.

The UNHCR has been forced to reduce all aspects of its operations in Lebanon, said Ivo Freijsen, UNHCR’s country representative, in an interview.

The agency cut 347,000 people from the UNHCR component of a WFP-UNHCR joint program as of April, a spokesperson said. Every family had been receiving $45 monthly from UNHCR, they added.

The group can support 206,000 Syrian refugees until June, when funds will dry up, they also said.

“We need to be very honest to everyone that the UNHCR of the past that could be totally on top of issues in a very expedient manner with lots of quality and resources — that is no longer the case,” Freijsen said. “We regret that sincerely.”

BAD TO WORSE

By the end of March, the UNHCR had enough money to cover only 17 percent of its planned global operations, and the budget for Lebanon is only 14 percent funded.

Lebanon is home to the largest refugee population per capita in the world.

Roughly 1.5 million Syrians, half of whom are formally registered with the UNHCR, live alongside some 4 million Lebanese.

Islamist-led rebels ousted former Syrian leader Bashar Assad in December, installing their own government and security forces. Since then there have been outbreaks of deadly sectarian violence, and fears among minorities are rising.

In March, hundreds of Syrians fled to Lebanon after killings targeted the minority Alawite sect.

Lebanon has been in the grips of unyielding crises since its economy imploded in 2019. The war between Israel and armed group Hezbollah is expected to wipe billions of dollars from the national wealth as well, the United Nations has said.

Economic malaise has meant fewer jobs for everyone, including Syrian refugees.

“My husband works one day and then sits at home for 10,” Merhi said. “We need help. I just want milk and diapers for my kids.”

DANGEROUS CHOICES

The UNHCR has been struggling with funding cuts for years, but the current cuts are “much more rapid and sizeable” and uncertainty prevails, said Freijsen.

“A lot of other questions are still to be answered, like, what will be the priorities? What will still be funded?” Freijsen asked.

Syrian refugees and vulnerable communities in Lebanon might be forced to make risky or dangerous choices, he said.

Some may take out loans. Already about 80 percent of Syrian refugees are in debt to pay for rent, groceries and medical bills, Freijsen said. Children may also be forced to work.

“Women may be forced into commercial sex work,” he added.

Issa Idris, a 50-year-old father of three, has not received any cash assistance from UNHCR since February and has been forced to take on debt to buy food.

“They cut us off with no warning,” he said.

He now owes a total of $3,750, used to pay for food, rent and medicine, and he has no idea how he will pay it back.

He cannot work because of an injury, but his 18-year-old son sometimes finds work as a day laborer.

“We are lucky. We have someone who can work. Many do not,” he said.

Merhi too has fallen into debt. The local grocer is refusing to lend her any more money, and last month power was cut until the family paid the utility bill

She and her husband collect and sell scrap metal to buy food.

“We are adults. We can eat anything,” she said, her voice breaking. “The kids cannot. It is not their fault.”

Kurdish PKK says held ‘successful’ meeting on disbanding

- The PKK will share “full and detailed information with regard to the outcome of this congress very soon,” it said

- In February, Ocalan urged his fighters to disarm and disband

ISTANBUL: The outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) held a “successful” meeting this week with a view to disarming and dissolving, the Kurdish agency ANF, which is close to the armed movement, announced on Friday.

The meeting resulted in “decisions of historic importance concerning the PKK’s activities, based on the call” of founder Abdullah Ocalan, who called on the movement in February to dissolve.

The congress, which was held between Monday and Wednesday, took place in the “Media Defense Zones” — a term used by the movement to designate the Kandil mountains of northern Iraq where the PKK military command is located, the agency reported.

The PKK will share “full and detailed information with regard to the outcome of this congress very soon,” it said.

In February, Ocalan urged his fighters to disarm and disband, ending a decades-long insurgency against the Turkish state that has claimed tens of thousands of lives.

In his historic call — which took the form of a letter — Ocalan urged the PKK to hold a congress to formalize the decision.

Two days later, the PKK announced a ceasefire, saying it was ready to convene a congress but said “for this to happen, a suitable secure environment must be created,” insisting it would only succeed if Ocalan were to “personally direct and lead it.”

The PKK leadership is holed up in Kurdish-majority mountainous northern Iraq where Turkish forces have staged multiple air strikes in recent years, targeting the group which is also blacklisted by Washington and Brussels.