KARACHI: Shareefa was 35 when she lost her husband to an illness almost a decade ago.

Uneducated, alone and left with the responsibility of taking care of her two sons, age 8 and 5, and a two-year-old daughter, the Afghan refugee hailing from the Kandahar province and currently residing in Pakistan, said she had no choice but to work as a domestic help for a meager amount, using her earnings to fund her children’s education.

When her eldest son, Akmal Hayatullah completed his primary school, the board of secondary education in Karachi refused to issue him a certificate for further studies.

“I visited the board several times for six months before I finally decided to discontinue my son’s education and sent him to work [as a mechanic] at a local workshop,” she said.

When things took a turn for worse and with so many mouths to feed, Shareefa was once again forced to stand on life’s crossroads, ultimately stopping the education of her second son, Zabihullah, and daughter, Arifa, too.

“Zabihullah is now working as a waiter in a restaurant,” she said.

Together, the family of four earn enough to get by, as Afghan nationals have very few or no opportunities for employment in the mainstream sectors.

Therefore, when Shareefa was selected by the UNHCR for the “train the trainers” program, her happiness knew no bounds.

After completing the three-month training program, where designer Huma Adnan took her under her wings in May, Shareefa, along with two other women, is now training 18 other Afghan refugees at the AHAN (Aik Hunar Aik Nagar) center, at Chhota Plaza, in Sohrab Goth.

Shareefa is hopeful that through the initiative she too will soon have her own small business.

Stitching the same set of dreams, one piece at a time, is Najeeba, one of Shareefa’s students, who says she is confident that one day she will start contributing financially to her family, too.

“My father works on daily wages. Like other Afghan nationals, my father is being offered little wages due to which he is finding it difficult to run the household. Give us the skill and we will show you how we can make many things,” Najeeba told Arab News.

She added that even though she wanted to continue her studies, lack of educational facilities and tough financial conditions were forcing her to stay at home. “If we have skills, we will also spend our lives according to our wishes,” she said. “Finally, we are having it,” she said.

Currently, three trainers -- Shareefa, Sitara and Sakina -- are teaching a group of six women each at the center. However, designer Adnan says she will select more trainers to reach and impact more women refugees through the program.

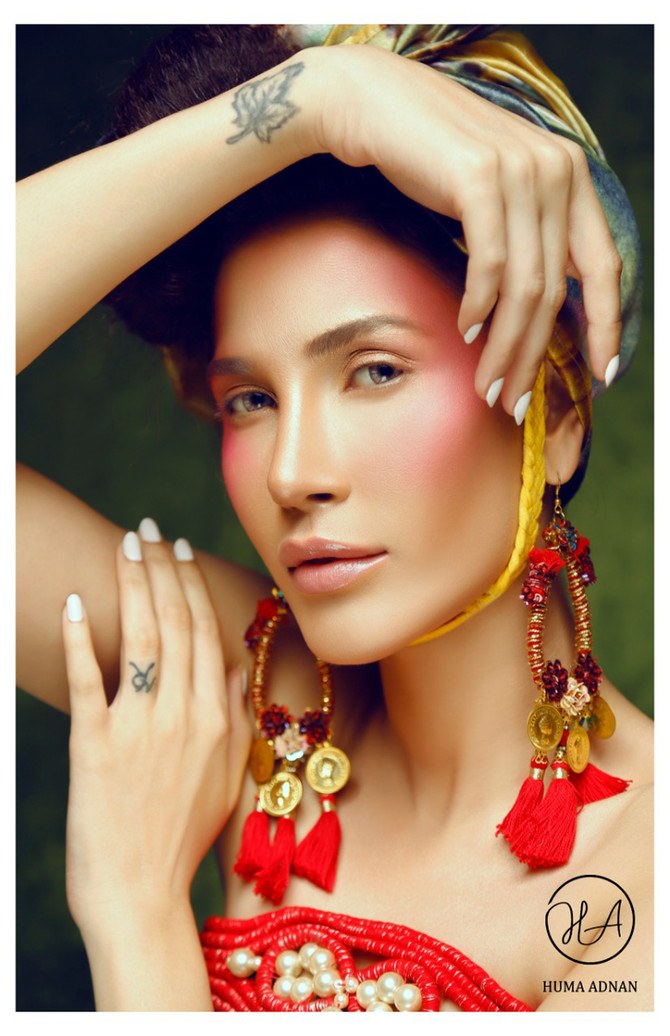

She added that the skillsets which these women will eventually acquire will help make them self-reliant in the long run. For that, one of the most important aspects of the program is to market the world-class handicrafts which these women are making. “To sell these in the international market, the best marketing practices should be adopted,” she told Arab while showing sample photographs from a fashion shoot for the jewelery made by the women.

The focus should be on “more quality and not on the quantity of crafts” made, she said, adding that the Afghan women “have shown that they can create the best” handicrafts.

“They are ready to learn, ready to improve and ready to improve their standard of living by working hard to earn a living. All they need is direction and mentorship,” she said.

Pakistan is host to 1.4 million refugees. “We will have to accept that they may hardly return to their homes. So, the best way to make them self-reliant and productive for the society where they live in is to turn them into skillful artisans,” she said, adding that it is the “collective responsibility” of all, including refugees’ agencies and non-government organizations, to realize this dream.

Adnan says every design created by the refugee women holds a special meaning for her. “I know the stories and hard work that is going into this project. Each piece represents beauty and love, loss, fears, and tears and you can see it in the perfection of their finished product,” she said.

Shareefa, on her part, said that the present seems like a dream. “The Afghan women remain at home. Even if educated they hardly come out of work. This program will lead them towards becoming self-reliant and ultimately changing their destiny.”