As nuclear power is increasingly being seen as a key element in tackling climate change, Saudi Arabia is moving toward adopting the renewable energy source.

According to a report last year by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a large increase in nuclear power could help keep global warming to below 1.5 degrees Centigrade, a target set as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

But to achieve that target, experts say the world needs to start reducing greenhouse gas emissions almost immediately.

“The IPCC report made clear the necessity of nuclear energy as an important part of an effective global response,” Agneta Rising, director general of the World Nuclear Association, told Arab News.

“Nuclear power is the only form of electricity generation that can deliver constantly, reliably, 24/7 without the production of greenhouse gas emissions. A nuclear power plant also takes up a much smaller area, in contrast to many renewables such as wind or solar.”

Dr. Peter Bode, former associate professor of nuclear science and technology at the Delft University in the Netherlands, said: “The need for electricity will increase by the conversion to electric cars for the next decade, and hydrogen-driven cars beyond 2030. Hydrogen gas is generated from water but also needs electricity, while a single nuclear power station produces energy equivalent to hundreds of wind turbines.”

Nuclear power is seen as especially well-suited to and beneficial in the Middle East, where energy demand is growing rapidly.

“It’s difficult to see alternatives in the Middle East for electricity needs without nuclear power as a major component in the energy mix,” Bode said. “In addition, nuclear power plants generate jobs.”

Across the region, countries are opting for the nuclear route. Construction of the Barakah nuclear power plant in the UAE is nearing completion, and all four reactors are expected to generate in the next few years.

Saudi Arabia has outlined ambitious plans for the development of nuclear generation, including next-generation reactors.

“Nuclear power is well-suited to meeting future energy needs in the Middle East. Energy demand in the region has risen rapidly in recent decades and is expected to continue to grow, with the development of large urban areas with high populations,” Rising said.

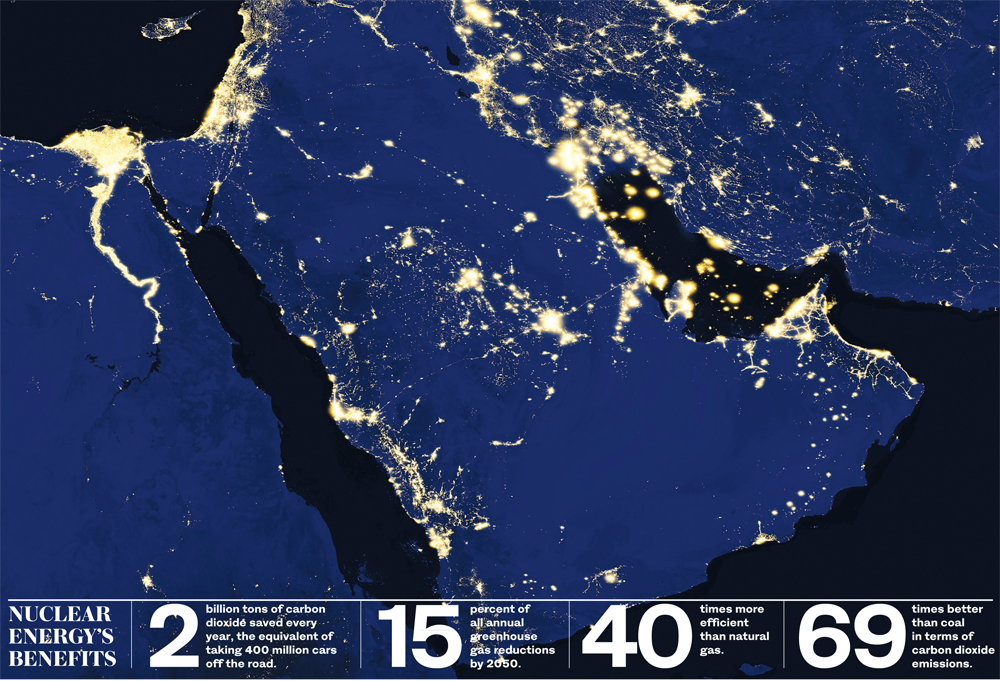

Sources: International Atomic Energy Agency, International Energy Agency

“The ability to generate more than 1 gigawatt of electricity from a compact plant makes nuclear generation well-suited to meet this demand.”

Last July, Saudi Arabia invited the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to conduct its Integrated Nuclear Infrastructure Review.

A team assessed the status of the Kingdom’s nuclear power infrastructure development, while providing detailed guidance.

Last week, the review was handed to Dr. Khalid Al-Sultan, president of the King Abdullah City for Atomic and Renewable Energy in Riyadh. It will be made public in 90 days.

“Saudi Arabia has made significant progress in the development of its nuclear power infrastructure,” said Mikhail Chudakov, IAEA deputy director general and head of the department of nuclear energy.

“It has established a legislative framework and carried out comprehensive studies to support the next steps of the program.”

The Kingdom has developed a national action plan, and earlier this month it had its first meeting to discuss the plan with the IAEA.

“This is indicative of the commitment of Saudi Arabia to make progress and to move the program forward,” Chudakov said.

“While the IAEA can provide support, the responsibility for closing any gaps and moving the program forward lies with the (Kingdom).”

Nuclear plants can also be used for desalination — on which the region relies heavily — and supplying industrial heat.

“Developing nuclear energy technologies will bring a lot of benefits to the Middle East,” Rising said.

“But countries should ensure that there’s a level playing field in their energy markets,” in which “nuclear energy is treated equally with other low-carbon technologies and recognized for its value in a reliable, resilient, low-carbon energy mix.”

She said countries should also ensure that there is an effective safety paradigm that focuses on genuine public wellbeing, and where the health, environmental and safety benefits of nuclear power are better understood and valued compared with other energy sources.

Dr. John Bernhard, former Danish ambassador to the IAEA, said: “Though renewable energy sources such as wind, solar and geothermal are becoming increasingly important, it’s clear that in the foreseeable future they’re far from able to meet the increasing global clean energy demands, especially in countries with fast-growing industrial development. So it’s essential to maintain, or when possible increase, the role of nuclear power as part of the energy mix.”

Public acceptance will prove crucial in that transition. Dr. Kenji Yamaji, director general of the Research Institute of Innovative Technology for the Earth in Tokyo and a nuclear physicist, said: “Potential contributions to climate-change mitigation by nuclear power would be huge if the nuclear option is considered by the public as a socially acceptable energy choice.”

He added: “There remains strong public concern over nuclear safety in Japan after the Fukushima accident. But the Middle East is an attractive new nuclear market, and strong government support will be key.”