In the international forum jungle, roamed by the big beasts such as Davos, Bloomberg and CERAWeek, how does a middle-ranking player like the Milken Institute compete?

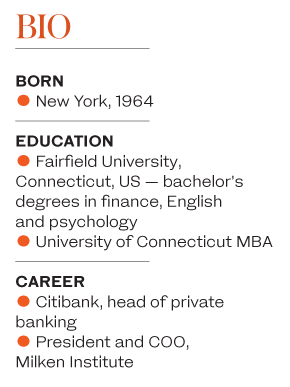

Richard Ditizio, the institute’s president and chief operating officer, responded confidently: “What differentiates the institute is that we operate at the intersection of health and finance.”

If that seems a little specialized, Ditizio goes to great lengths to explain that health is not just about clinics or treatments, but is the totality of human well-being, from demography through to mortality; and finance is not just about raising money, but is the complete spectrum of activities by which people provide the resources for their lives.

Health and finance, he believes, are at the heart of everything else. The institute calls itself an “independent economic think tank,” but its raison d’etre is to “apply market-based principles” to “social issues,” which in effect boils down to health and finance. “There is lots of robust territory for us where those two meet,” Ditizio said.

The institute’s lineage demonstrates those values. It was founded in 1991 by Michael Milken, the financial innovator who virtually invented the idea of the “junk bond” (high-yielding corporate debt).

When the world of finance went sour, Milken devoted a considerable portion of his time and wealth to health issues, funding philanthropic initiatives to tackle intractable medical problems, such as melanoma and other life-threatening diseases. In 2004, Fortune magazine gave him a front page with the title “The man who changed medicine.”

Ditizio will be in Abu Dhabi this week, heading the second MENA summit that the institute has held in the region. The Middle East is a virtual petri dish for institute theory, as he explained.

“I’ve just come from Japan, where the problem is the aging population, but in MENA it’s the exact opposite. Here the issue is how to make youth function as part of a workforce at 40, 50 or 60 years old,” he said.

This, of course, is one of the main aims of the Vision 2030 strategy in Saudi Arabia: To provide meaningful economic lives for the Kingdom’s large youthful population, in a situation where the state will not be able to provide public-sector employment forever.

Ditizio likes what he has seen and heard of the Saudi strategy. “Having a plan is a good thing, for a nation or a business. Diversification, education, health and gender are the areas we see as important, and these are the key areas of Vision 2030, too.

“You can always tweak strategy as you go along, but I think it is heading in the right direction. If there are episodic things that distract from the norm, the strategy will help you get back on track. It is a touchstone to overcome obstacles,” he said.

However, he warned of the risk that big transformations such as those being undertaken in Saudi Arabia might destabilize society. “Stability is paramount. People beholden to the old way of life may find it tougher. It could get messy along the way, but the overall results will be positive,” he said.

Women’s empowerment is a big theme for the institute. Did Ditizio think that the changes in women’s status in the Kingdom were happening fast enough?

“You don’t want to permanently exclude 50 percent of your workforce from participating in the economy. Growth in gross domestic product will escalate if women are allowed to participate, and if you allow women to balance their personal and professional lives, it will grow the pool and lift everyone,” he said.

To some extent, the institute practices what is preaches with regard to gender. In comparison with some other global forums, which are still overwhelmingly male dominated, Milken has more than half of its workforce made up of women, and has a target of 30 percent female participation at its events.

“Lots of studies show that companies with more diverse boards have better financial performance. Those that don’t often fall behind,” he said.

Like all big think tanks, the Milken Institute has to gauge its initiatives on issues such as health and gender equality against the broader backdrop of geopolitical and economy performance. There is little point planning a long-term strategy on medical or social issues if the world is going to be turned upside down by, for example, a confrontation between the US and China on trade, or another financial crisis.

Stability is paramount. People beholden to the old way of life may find it tougher. It could get messy ... but the overall results will be positive.

Richard Ditizio

The analogy Ditizio uses — especially in relation to fears of a US-China trade war — is illuminating. “It’s like the difference between climate change and weather. There was a polar vortex in the US recently, but one cold spell doesn’t mean climate change isn’t happening.

“So although there may be an acute trade spat at the moment between the US and China, each country is so important to the other that I don’t think long term they are going to set out to derail each other’s economies,” he said.

Ditizio applies the same reasoning — long-term progress versus short-term “episodic” events — to the Middle East, too. “In MENA, we are all aware of the specific risks, but are they systemic, life-changing risks? If you develop economies in order to give people a more prosperous life, they are less likely to get involved in terrorism.”

That introduces another key theme of the Milken Institute’s thinking — the power of financial market forces to bring about desirable social and economic change.

“There are pockets of capital around the world, some estimate it at $30 trillion, that are not being deployed. They are on the sidelines of the global economic system, in offshore funds, invested in other things outside the system. It’s capital that is not being used. If you can deploy that, you can help lift economies and generate a nice financial return,” he said.

That brought us to one of the big debates in the forum circuit at the moment: The role and power of philanthropy. At the World Economic Forum in Davos earlier this year, there was a disagreement between major donors such as Bill Gates and those who felt that big-name philanthropy was overrated and should now step aside in favor of a more efficient global tax system.

It is an area where Ditizio, as a former head of private banking for Citi North America, dealing with high-net-worth individuals on a daily basis, has some expertise.

“I think there is a disproportionate amount of attention given to the big-name philanthropists. There was something like

$350 billion donated in the US last year, and most of it was not by the ‘big’ philanthropists. But philanthropy still has a role, and that’s especially true of the Middle East, with the system of voluntary giving via zakat (Islamic charitable giving),” he said.

The other theme that he predicts will emerge at the MENA summit this week is technology, and its potential to upend traditional ways of thinking across health, finance and the regulatory systems that govern them.

“We are seeing it in fintech, and how that is changing the regulatory relationship; we’re seeing it in the clinical field, where artificial intelligence (AI) could be running synthetic trials of medicines,” he said.

The changes wrought by technology are fundamental. “Today we cannot live without an iPhone. Twenty years ago we had nothing,” he said.