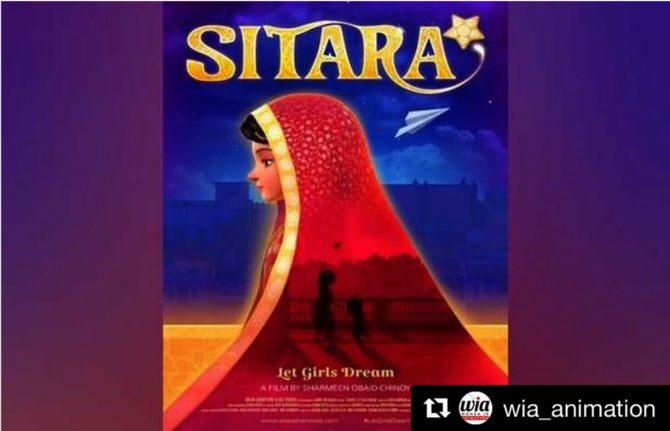

ISLAMABAD: Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy announced on October 28, 2019, that “Sitara” will release on Netflix USA and global, the first Pakistani animated film to get a global release on the streaming platform in early 2020.

Chinoy says she wants “Sitara” to strike a chord with young girls and their parents inspired by real-life stories, the animated film focuses on the impact of social evil.

When Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy released her latest animated film in New York this month, she hoped it would encourage people to support their daughters in realizing their dreams.

Sitara (star in Urdu) is the award-winning Pakistani director’s latest offering and is focused on the social evil of child marriage in South Asian countries, including Pakistan.

“I always wanted to start a global conversation about why we are not investing in the dreams of our daughters?,” Chinoy told Arab News in an email interview on the inspiration behind the film.

The feature revolves around the story of a 14-year-old girl named “Pari” who wants to become a pilot but sees her dream “ruefully snatched” away from her after she is forced into an arranged marriage.

Child marriage is often a focal storyline in animated films from Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy's production company SOC Films. Chinoy believes the medium transcends age groups and can be watched by everyone, children and adults alike. (Photo taken from Instagram)

An expert on the topic after having made several films on child marriage – a centuries-old issue which continues to plague several South Asian countries – Chinoy is hoping her latest venture reaches girls of all ages and their parents, too.

A study conducted by UNICEF in 2017 estimated that 21 percent of Pakistani girls are married before their 18th birthday.

When asked if any particular story had struck a chord with her, she said that the film is “woven from the testimonies of many young girls.”

“[It’s about] their broken promises and what it means to them when they feel powerless and are unable to do anything to change their circumstances,” she added.

Animation, a medium which Chinoy often employs in her initiatives, continues to be her go-to choice in this film, too.

“I want children to see a reflection of themselves on the big screen; to see their clothes; to see their streets; to see their world come alive,” she said before highlighting some of the major obstacles faced by young girls today.

“Girls around the world are told from a young age what they can and cannot achieve when they grow older they are told that “this is not something girls do,” she said, denouncing the “artificial limitations on young girls today.”

“In boardrooms, in parliament and in positions of leadership, girls and women are routinely excluded and kept out. In 2019, that is unacceptable and the ownership lies on us, the women, to fight back to have a greater say so that we can make decisions for other girls,” she said.

She says that one needs to focus on the tinier details before looking at the larger picture to understand the depth of the problem.

“When a table is laid out [a girl child] is the last to be given food, when the clothes are made she is the last to get them. To go to school, she is the last one to get books,” Chinoy said, adding that this is particularly the case in South Asian countries.

“In other societies, girls might get an education but when it comes to jobs and promotions they are held back... Depending on the society and community, there is still discrimination, there is still misogyny, there is still exclusion,” she said.

When asked about what steps can be taken to counter the issue of child marriage, Chinoy stressed that the change needs to start at home.

“One of the factors that play heavily into girls leaving school and being forced into marriage is trust and responsibility. Parents feel that when a girl reaches a certain age...they would rather get the girl married off. There is this sense of burden and responsibility that forces girls into this life of early marriage,” she said, adding that the onus lies on us “to change the mindset of parents.”