DHAHRAN: A new photography exhibition at the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture (Ithra) in Dhahran captures reflections of daily life and society in the Arab World. “Mara’ina” (Our Mirrors) explores the lives, culture and identity of Arabs living throughout the Middle East.

“Classical civilizations believed the mirror showed images of the soul,” the curator of the exhibition, Candida Pestana, says. “It was considered a medium of self-perception, an instrument for self-doubling, and a cult object with natural properties, helping us communicate with our inner selves.”

The exhibition space expands on the theme with mirrored walls. “It is purposefully devised so that you can see yourself constantly,” says Pestana. “We wanted the viewer to have the opportunity to interact with the works in a very private space.”

“Mara’ina” features works by 22 artists from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Syria, Somalia, Tunisia, Morocco, Lebanon, Palestine, Italy, Canada and the USA, including Akram Zaatari, Camille Zakharia, Hazem Harb, Hela Ammar, Hicham Benohoud, Hrair Sarkissian, Mustafa Saeed, Osama Esid, Rania Matar, Robert Polidori, Sultan bin Fahad, Taysir Batniji, and Karim El-Hayawan

The exhibition is supported by the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, which has lent nine photographs to the exhibition. In addition, three newly commissioned works by Saudi artists Faisal Samra and Tasneem Alsultan and Italian photographer Michelangelo Pistoletto anchor the show.

Some of the artists draw from their own experiences and upbringing, others reflect on the effects of the socio-political events. But all of them capture the story of a changing region.

“We chose artists that talk about the Arab world in terms of home, society and family,” Pestana tells Arab News. “We hope that the exhibition will trigger, like its name, some sort of reflection on the Arab World and the realities of the people portrayed.”

Tasneem Alsultan

‘Saudi Love Stories’

The acclaimed Saudi photographer’s “Saudi Love Stories” series began as a personal venture when Alsultan was married for the first time at the age of 17. By the age of 21, she was a mother of two. She is now divorced. In this ongoing project, Alsultan says she wanted “to answer the question that many shared: Do we need marriage to signify that we have love?” Do you need a husband to have a significant life?” In the process, the artist encountered women who shared marriage theories and experiences more complex than she expected. The series has its own dedicated room in “Mara’ina.” One work at least, commissioned by Ithra for the show, reveals the story of an arranged marriage that ended happily. The woman is a doctor and her husband is a poet. Alsultan’s photographs reveal the couple happily going about their life and work together.

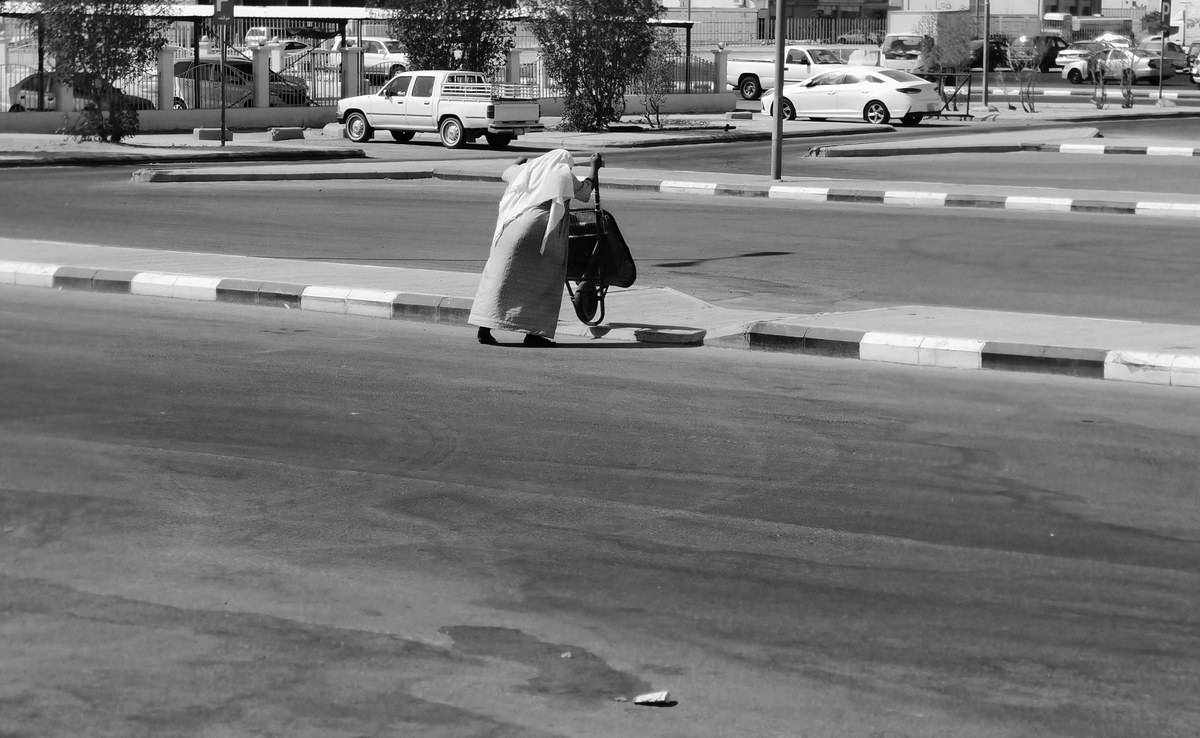

Faisal Samra

‘People in Context’

The Bahrain-born Saudi artist’s commissioned work for Mara’ina, consisting of photographs and videos, reveals the daily lives of people in Al-Hasa, in the Kingdom’s Eastern Province. “Al-Hasa is the origin of my family,” the artist tells Arab News. “I have sweet memories of the place. Doing this project allowed me to go back in time and experience nostalgia for this region and its history. Al-Hasa played an important role in regional history as a gateway between the Arabian Peninsula and the outside world.

“Documenting and immortalizing the … people living there will help us understand and relate to this community in a humanistic fashion,” he says.

Robert Polidori

‘Saudi Family’

The acclaimed Canadian photographer took this shot of Saudi tourists visiting Jerash, Jordan in the 1990s (along with images of tourists from other countries). His photographs show a culture on the verge of social change. While Polidori was shooting one of the men approached him, fascinated by his Pentax camera. Polidori asked to take their portraits. At first only the men agreed, but after three shots, they allowed the woman to join. Polidori then captured the smiling group of three Saudi men and one woman next to an ancient Roman monument.

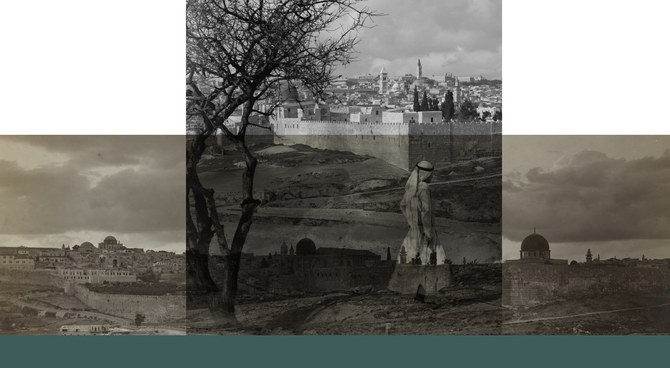

Hazem Harb

‘She Is Memory’

Born in 1980 in Gaza, Harb utilizes old photographs and archival material that he has collected over the years, transforming them into poignant conceptual compositions. Collage enables him to create a discourse using a mix of references to a Palestinian past — one that relies on history as much as it does myth. Through his art Harb asks the question: How do you evoke the past of a people denied its right to existence?”

The 2017 series on view in “Mara’ina” is part of Harb’s ongong series “Power Does Not Defeat Memory.” The artist tells Arab News: “It refers to the concept regarding how the power of colonialism and occupation couldn’t affect the collective and personal memories of the Palestinian people pre-1948.”

Karim El-Hayawan

‘Cairo Cacophony’

In the Egyptian artist’s video installation, the viewer experiences the sights, sounds and general chaos of Egypt’s capital. “In Cairo you cannot separate the visual from the cacophony of Cairo’s streets,” says El-Hayawan. “The cacophony is intricately part of the visual itself. You cannot separate one from the other.” What is especially striking about this particular work is the soundtrack, assembled from three types of Egyptian music ranging from classical to contemporary to pop, and revealing the multi-faceted world one encounters in the city.

Rania Matar

‘Invisible Children’

Matar’s 2014 series of empathetic portraits of Syrian and Palestinian children living as refugees in Lebanon — some begging for money, some selling flowers to get by — is named because Matar felt that the children seemed invisible to passers-by. So commonplace were these children on the Lebanese streets that they seemed to blend into the graffitied walls in front of which they stood.

Hicham Benohoud

’30 Houses’

The Moroccan artist is known for his poignant black-and-white images that merge realistic scenes from everyday life with abstract sensitivity. In “30 Houses,” he photographed families throughout Paris over the course of a prolonged stay in the French capital. In each home he visited, he asked the residents to place themselves in an unusual situation: lying on a kitchen table, attaching themselves to a wardrobe, or even cramming themselves underneath a stack of chairs. “For me, it was important to know nothing about the people I went to,” he writes in his artist’s statement. “Each statement was improvised, depending on what happened —or not — with the families.”