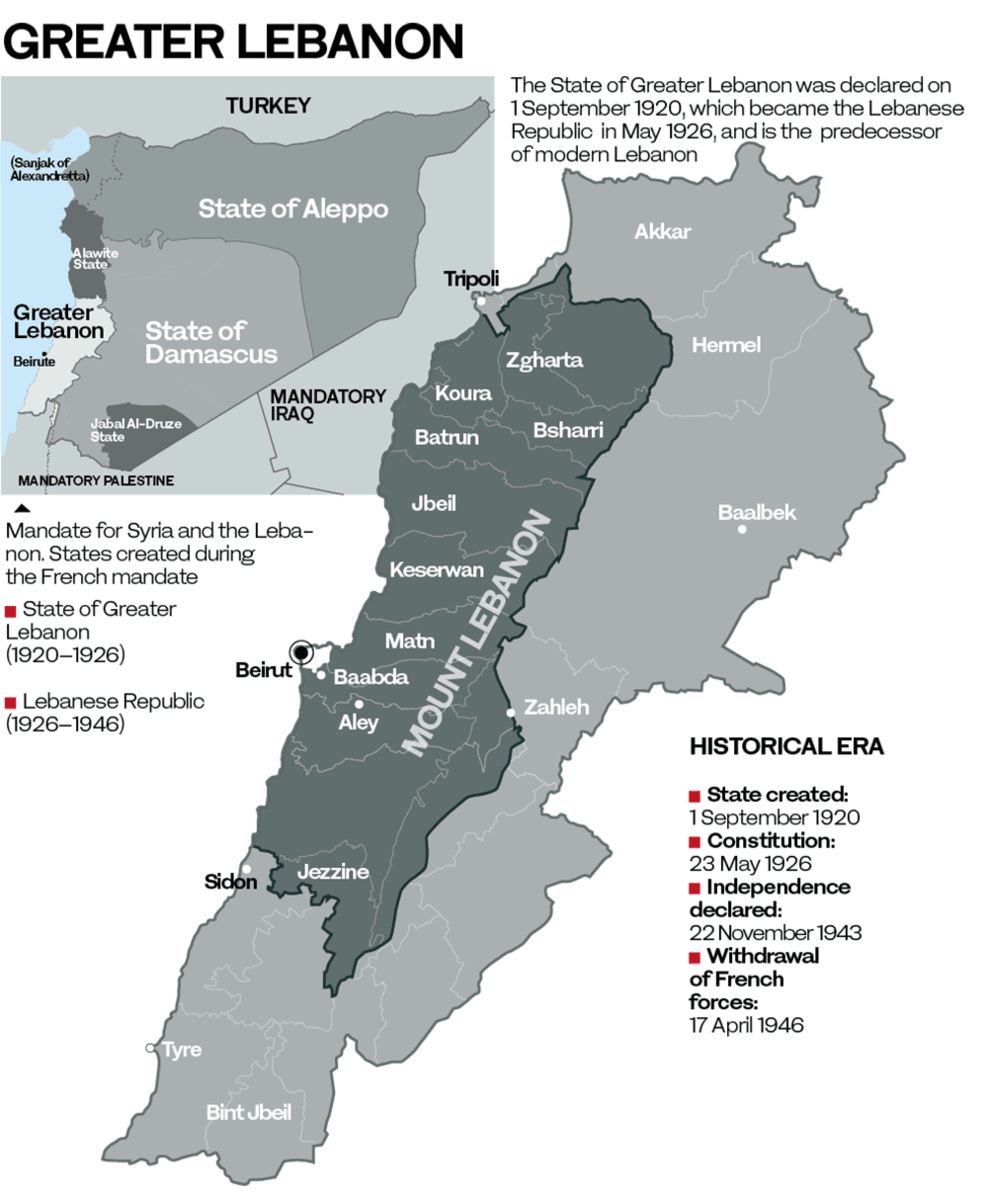

PARIS: The symbolism could not have been stronger. On Sept. 1, 1920, French Gen. Henri Gouraud, representing the French mandate authority, proclaimed the State of Greater Lebanon from the Pine Residence in Beirut. On that day, Lebanon set out on its path toward independence, which it gained — for better or worse — 23 years later, on Nov. 22, 1943.

One hundred years later, as French President Emmanuel Macron inspected the devastation caused by the massive explosion of Aug. 4, 2020, at the Beirut port, Lebanese people, expressing their anger at the incompetence of the Lebanon’s authorities, called for the country to be placed under “French mandate for the coming 10 years.”

The French leader promised to return on Sept. 1 for the centenary celebrations of the creation of Lebanon. Meanwhile, Paris stepped up its efforts to support those affected by the explosion, and to urge Lebanese leaders to begin much-needed reforms to deal with the serious economic and financial crisis facing the country.

French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian’s July 8 cri de coeur aimed at the Lebanese authorities — “Help us help you, dammit!” — reflected growing concern in Paris over the very future of Lebanon.

Relations between the two countries go back much further than the historic date in 1920, which only consecrated ties that were several hundreds of years old. One can trace the beginning of France’s links with Lebanon to St. Louis, the 13th-century monarch who recognized the Maronite nation in Mount Lebanon and was committed to ensuring its protection.

However, it was the capitulation agreements between the Ottoman empire under Suleiman the Magnificent and the European powers, including France, ruled by Francois I, that paved the way for France in the 14th century to forge deeper relations with the Lebanese, with the aim of defending the empire’s minorities, especially Christians.

In 1860, after the massacres of Christians in Mount Lebanon, the French, under Napoleon III, intervened militarily to restore order. This allowed the creation, on a political level, of the Mutasarrifate, an administrative authority that ushered in a period of stability until the First World War.

With the end of the Ottoman empire at the beginning of the 20th century, Lebanon was put under French mandate. Since then, Paris has always played a privileged role in the land of the cedars. Beirut was at the center of relations between these two entities, especially its port, which was largely destroyed in the Aug. 4 blast.

When the Count of Pertuis was granted the concession for the modernization of the port, he opened Beirut to the world. The city began to develop, mainly thanks to the silk trade between Lyon and the Lebanese mountains. It was the installation of mainly French-speaking religious missions in the 19th century, and the creation of schools and Saint Joseph’s University that made Beirut and Mount Lebanon what they are today.

Lebanon thus became the center of a strategic vision for France, which saw it as the flagship of the Beirut-Damascus-Bagdad axis in the face of the British-controlled Haifa-Amman-Bagdad axis.

The establishment by the French of the railway that connected Beirut to Mount Lebanon, on the one hand, and Damascus to Baghdad on the other, ended up giving Beirut a new dimension by shaping it economically, politically and culturally.

France was thus actively present, long before the mandate instituted by the League of Nations in April 1920. The proclamation of Greater Lebanon was the crowning achievement of a relationship that has been established simultaneously on religious, cultural, economic and political levels.

A French patrol, part of a multinational peacekeeping force, outside the southern Lebanese village of Al-Tiri in 2006. (AFP)

France’s political support to Lebanon has been immeasurable, especially during the 1975-1990 war. Paris has repeatedly sent envoys to negotiate cease-fires and to unblock political crises. The July 2007 meeting at the Chateau de La Celle-Saint-Cloud to initiate a dialogue between different Lebanese political forces is a case in point.

The road map recently presented by President Macron is the latest example of this approach.

France’s presence in the UN and multinational forces formed several times to intervene in Lebanon can hardly be glossed over. French soldiers paid dearly for their country’s support for Lebanon, such as during the 1983 Drakkar building attack, blamed on Hezbollah and Iran, which killed 58 French paratroopers. The assassination by the Syrians of Ambassador Louis Delamare in 1981 is another case in point.

In addition, France has been present in UNIFIL forces since 1978 and remains one of its principal contributors.

On the financial front, as the linchpin of the support group for Lebanon, France has always been a mobilizing force for donors. In recent years, various conferences had been organized to help Lebanon, notably Paris I, II and III under the leadership of former President Jacques Chirac, as well as the CEDRE conference in 2018.

It is a friendship that has been marked by Chirac’s unwavering support for Lebanon, especially after the assassination of Rafik Hariri in 2005. France has always been present in the most difficult times to lend a helping hand. It is also the country that has the most leverage as it tries to talk with all parties, while other countries, especially regional ones, take more radical positions.

Paris is virtually the only power that has always worked for the unity, stability and sovereignty of Lebanon. A special friendship connects the two countries beyond strategic and economic interests — a friendship epitomized by President Macron’s words in Beirut on Aug. 6: “Because it’s you, because it’s us.”