Turkey’s rising role as a regional disrupter

https://arab.news/bgtvh

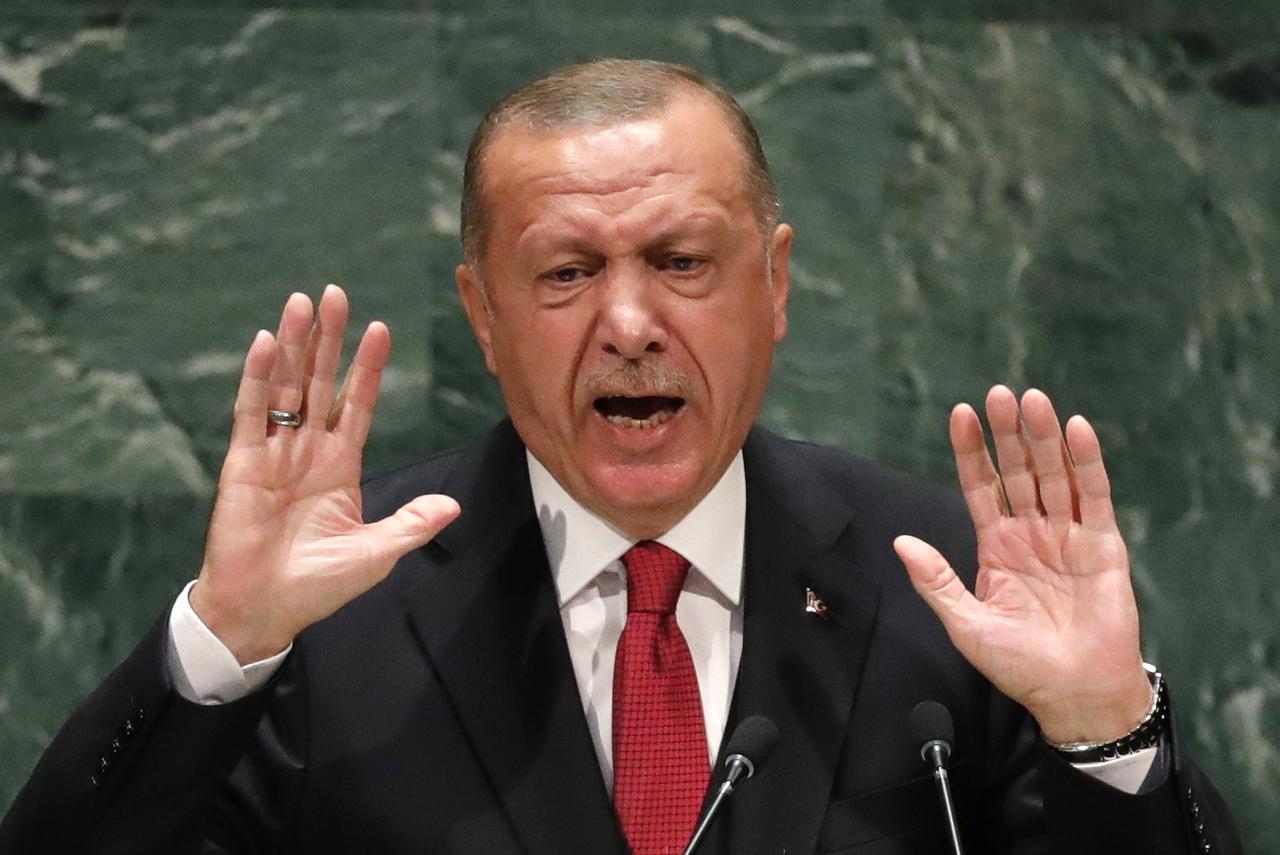

With Turkey’s latest intervention in the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is extending his country’s foreign adventures from the Caucasus to North Africa, raising questions about Ankara’s controversial role as a major regional disrupter. Erdogan’s populist approach to regional crises reflects a desire to reshape Turkey’s place in the international arena. But what is it exactly that he wants to achieve?

In a speech last week, he complained about the failures of the post-Second World War order, just as he had before about Turkey’s grievances following the First World War, which restricted his country’s maritime access in the Aegean. In his words: “There is no chance left for this distorted order, in which the entire globe is encumbered by a handful of greedy people, to continue to exist the way it currently does.” In almost all of his speeches, Erdogan underlines the so-called Turkish exceptionalism while portraying the country as a victim.

Pundits have talked about Erdogan’s obsession with reviving Turkey’s Ottoman past. His foreign adventures betray a desire to reshape the region’s geopolitical status under an emerging, militarized Turkey. Even as he sides with Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute, he does so out of a superior approach as the titular head of the Turkic peoples, egging Azeri President Ilham Aliyev not to accept an unconditional cease-fire. By sending Syrian mercenaries and weapons to Azerbaijan — an allegation denied by Aliyev — Erdogan is demonstrating how he views the region and its people: Former Ottoman territories and subjects that he can manipulate.

His unconventional approach to regional conflicts has put Turkey in a unique, albeit difficult, position. Despite being a major NATO member, he has built a shaky alliance with Russia’s Vladimir Putin, as well as with Iran over Syria, where his ultimate objectives remain vague and suspicious. Against US warnings, he has obtained the Russian S-400 air defense system, thus forcing Washington to cancel its F-35 fighter jet deal with Ankara and impose sanctions.

While being an ally of Moscow in Syria, Erdogan has taken the side of the Government of National Accord (GNA) in Libya as Putin backs the Libyan National Army of Khalifa Haftar. His support for the GNA has gone beyond diplomatic backing: He has violated UN resolutions by sending weapons and mercenaries to support Tripoli’s fragile government. Erdogan also signed a controversial maritime deal with GNA Prime Minister Fayez Al-Sarraj that encroaches on Greece’s territorial sovereignty. Top aides have described Libya as a former Ottoman territory and have pledged never to leave.

In the ongoing intra-Libyan peace discussions, the main stumbling block is the removal of all foreign players. Ankara’s position on this crucial issue is vague and the risks of the talks collapsing because of this are high.

In Syria’s Idlib, Turkey continues to provide support to extremist groups, while Erdogan has pledged that Turkey will wipe out the groups it deems to be terrorist — i.e., the Syrian Kurds — if others fail to keep their promises. Turkey has become part of the problem that is preventing a political solution to the nine-year-old Syrian conflict. It has been accused of transferring Syrian refugees to populate abandoned Syrian Kurdish towns in the north of the country. In both Syria and Libya, Erdogan’s kinship to the Muslim Brotherhood has been a key ideological factor in charting his policy.

Last week, the EU threatened Turkey with sanctions over its dispute with Greece in the eastern Mediterranean. Relations between Ankara and the EU, particularly France, have been tense over Syria, Libya and now Greece. After weeks of heightened tensions, Turkey agreed to recall an exploration vessel from the Aegean and begin talks with Athens. Turkey’s grievances over maritime borders may be reasonable, but its maverick style of violating Greek and Cypriot waters does not help its case.

Today, Ankara is involved in active disputes with all of its neighbors and beyond. Erdogan’s foreign adventures have hurt the Turkish economy and reversed much of its gains. His popularity at home has been dented. The main question remains: What does Erdogan really want? His alliances with Moscow and Tehran are temporary, as the agendas of these countries intersect with his at times and contrast at others. Turkey’s policies have polarized the Sunni world and isolated it from its neighbors. Now Erdogan finds himself on the opposite side to Putin over Nagorno-Karabakh, while their agreement in northern Syria faces collapse.

Erdogan is demonstrating how he views the region and its people: Former Ottoman territories and subjects that he can manipulate.

Osama Al-Sharif

With all these conflicts, which reflect badly on Turkey’s economy, currency and human rights, Erdogan is overreaching and he may soon find himself facing multiple foreign policy challenges. It is ironic that, in the course of the past few years, he has failed to respond to calls for, or even suggest, peaceful engagement. Syria’s Kurdish minority is not the issue, but Turkey’s Kurds are. He has squandered multiple opportunities to fix this problem peacefully.

In the end, while complaining about a distorted world order, Erdogan has become a major disrupting force in that very same order.

- Osama Al-Sharif is a journalist and political commentator based in Amman. Twitter: @plato010