KABUL: Back in the spring of 2013, Tajik Mohammed was enjoying his leave in the small garden of his family home in the lush village of Kapisa when he learnt that the Taliban had put him on a blacklist. His crime? He was working as a translator for the US military.

Under cover of night, the high-school graduate was forced to flee 110 kilometers south to Kabul, the Afghan capital, where he has remained ever since. His family followed after the Taliban “threw a hand grenade one day” at their house, thinking he was there.

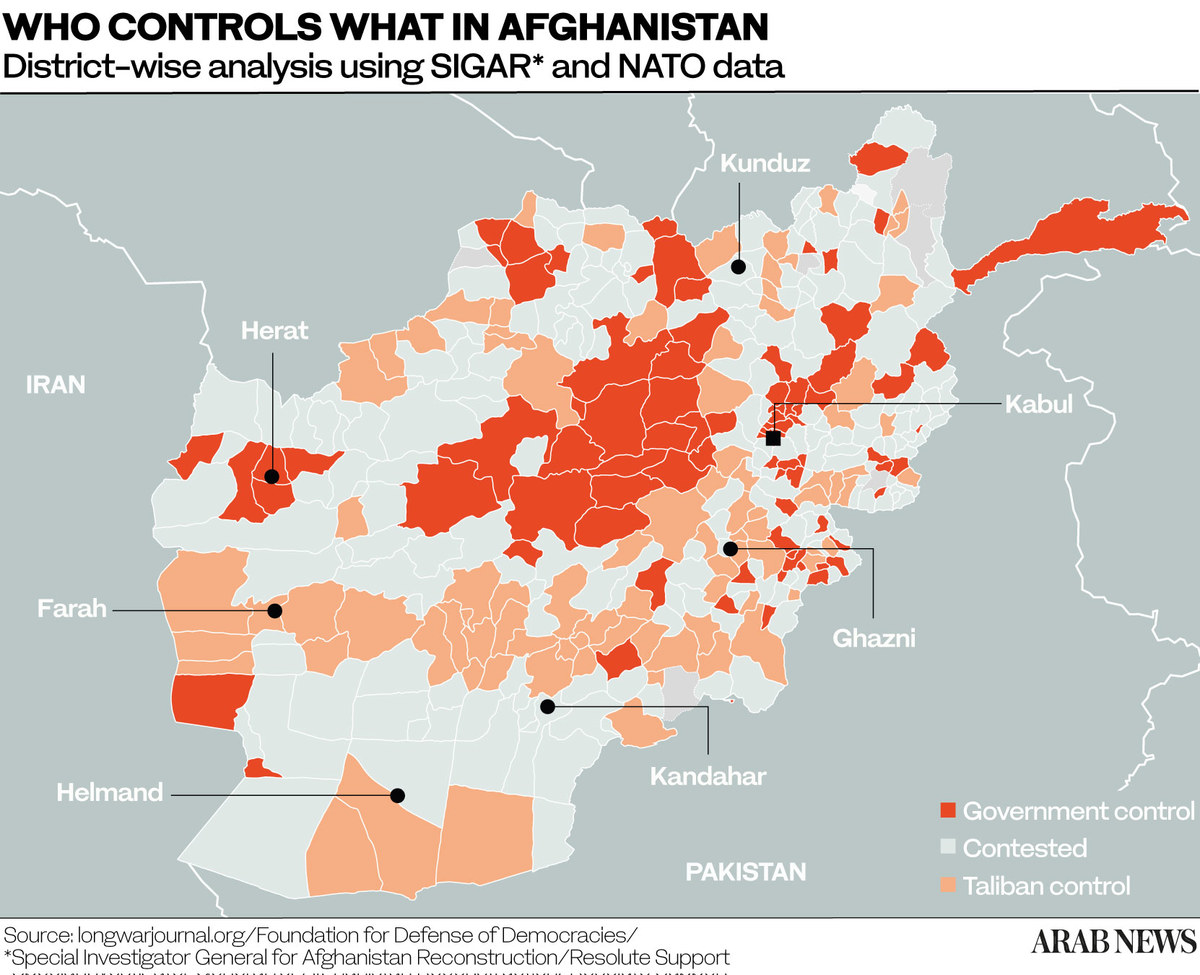

Mohammed, 32, worked for American troops in restive Ghazni province, which lies on the main highway leading to the Taliban’s bastion of support in the south.

He subsequently lost his job for failing to return to duty on time because he could not travel by air from Kapisa to Ghazni. He pointed out that if he had taken the trip by road, the Taliban would have killed him.

He and thousands like him are living in fear. In April, US President Joe Biden announced that he would be withdrawing the estimated 3,500 American troops stationed in Afghanistan by September, 20 years after the Al-Qaeda attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C.

(FILES) In this file photo taken on April 30, 2021 Afghan former interpreters for the US and NATO forces gather during a demonstration in downtown Kabul, on the eve of the beginning of Washington's formal troop withdrawal -- although forces have been drawn down for months. (AFP)

The withdrawals started on May 1. Departing with the American forces are their NATO allies and thousands of foreign military contractors. They leave behind those Afghans who have worked as translators, cooks, cleaners, and guards. Many are fearful that the militants will seek retaliation.

US-led efforts to reconcile the Taliban with the government of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani in Kabul have not borne fruit since talks began in Qatar last year.

Last week the Taliban, a grouping of mainly Pashtun militants who harbored Osama bin Laden and ruled Afghanistan for five years until 2001, said that they no longer considered the former employees of foreign forces as “foes.” But the militants noted that the workers needed to show “remorse” and should not use “danger” as an excuse to bolster their push for a “fake asylum case.”

In the past, the Taliban openly preached that Afghan translators should be killed. “You are a legitimate target for the Taliban even if you have served for one day for the foreign forces. I have no faith in the Taliban’s promise,” Mohammed told Arab News.

“Who killed so many journalists and civil society activists? Of course, (it was) the Taliban. But they did not take responsibility for them. We risked our lives while working for the foreign forces and now that they are leaving, there is no guarantee at all for our future and we face risk again,” he said.

Mohammed is a member of the Afghans Left Behind Association (ALBA), a union of 2,000 former translators and workers. The group was recently formed with the purpose of highlighting the voices and concerns of those who say they will be targeted once NATO forces leave.

Last week, ALBA held its first large-scale gathering under tight security in Kabul. A number of the former translators wore masks to protect their identities. No One Left Behind, an American non-profit organization that advocates for the relocation of Afghan interpreters to the US, said that according to US media reports more than 300 translators or their relatives had been killed since 2014.

Omid Mahmoodi, an ALBA press officer, said the Taliban killed at least one member of the union, named as Sohail Pardis, as he was driving in Khost province in southeastern Afghanistan, near the border with Pakistan.

In April, US President Joe Biden announced that he would be withdrawing the estimated 3,500 American troops stationed in Afghanistan by September. (AFP)

Another translator said he had moved to Kabul from his native Nangarhar province after receiving a threatening telephone call, naming him as an “apostate” who “deserved to be killed.”

Thousands have submitted applications for special immigration visas (SIVs) which allow them to emigrate to the US. Successful applicants need to prove that they served with US forces for at least two years and demonstrate that they provided “faithful and valuable service.”

This is usually attested by US military officers in the form of a letter of recommendation. Successful applicants typically also need to show that they have received evidence that they had been threatened. Those who are unsuccessful often lack documentation or are the subject of “derogatory information.”

The translators have been the eyes and ears for American troops and accompanied them during military campaigns against the Taliban and other militants. They have helped with the arrests of insurgents as well as the controversial searching of homes.

They have also acted as cultural advisers in what is a highly conservative society, helping foreign troops understand tribal, ethnic, and religious sensitivities, while in addition coordinating with Afghan forces.

Mohammed has recently applied for an SIV at the American embassy in Kabul. Thousands of translators from Afghanistan and Iraq have relocated to America using this mechanism as a reward for helping the US troops. “The answer I got through an embassy email asked me why I was terminated, where my recommendation letters were, etc,” he said.

“But the people we worked with in the US military have gone home, changed their addresses and even their profession, so it is tough for us to get hold of them, get the answers and pass them to the embassy here.”

Officials at the US embassy said they could not provide data on the percentage of applicants who had been turned down for an SIV or the number of former translators and employees who had been killed over the years.

Feraidoon, a 28-year-old former translator in Ghazni, told Arab News that he had had his SIV rejected in 2015 but had recently applied again. “The embassy says I do not have sufficient recommendation letters. We have no trust in the Taliban and see no commitment in them because they consider us as traitors, sell-outs and spies,” he said.

Mohammed Basir, 46, who worked for five years with French troops in Kapisa until 2013, said he had appeared in press conferences while translating on TV and had become a “known face” and feared reprisal. “The Taliban will spare no time to behead us if they capture people like me,” he added.

The Taliban said those who worked with foreign forces needed to show “remorse” and should not use “danger” as an excuse to bolster their push for a “fake asylum case.” (AN photo/Sayed Salahuddin)

A number of former translators whose cases were denied in the past have fled Afghanistan, according to ALBA. Akhtar Mohammed Shirzai escaped to India in 2013 with his family. He has been living there since in the hope that he will be able settle in a coalition country because he served with NATO’s media branch.

He applied for an SIV from India in 2016 but was rejected because he did not have a letter of recommendation from his superiors in Kabul. He applied again in May and is now waiting anxiously.

On the Taliban’s offer of an amnesty, Shrizai said: “I heard about it, but I personally do not believe in that because the Taliban are not monolithic. There are different groups with different ideologies and thinking among them.”

In Kabul, Ayazuddin Hilal, who worked for American forces in a number of regions, said the former translators “could not attend wedding ceremonies or funerals back in their villages and even in secure areas where they live. Residents of the area do not treat them well because of their service for the foreign forces.”

He noted that a friend and colleague had also wanted to move to Kabul because of security threats in Nangarhar but was killed by a bomb blast. “I hope the politicians in the US and other capitals take a wise decision on our fate,” he added.

Twitter: @sayedsalahuddin