DUBAI: Since Syria’s civil war began nearly a decade ago, thousands of refugees have crossed the border into Turkey. The city of Mardin, 30 kilometers inland from the Syrian border, is currently home to more than 80,000 displaced Syrian refugees, including children.

One homegrown non-governmental organization is on a mission to put a smile on those children’s faces by teaching them analog photography through the ongoing, mobile project Sirkhane Darkroom, led by Syrian photographer and refugee Serbest Salih.

The project is an offshoot of the Sirkhane (which means Circus House) school, which was founded in 2012 and — aside from offering photography and music workshops —specializes in teaching young adults circus arts including acrobatics, juggling, and theatre performance. More than 3,000 youngsters in the Mardin Province have so far participated in Sirkhane’s various programs.

Ilava while taking photos. (Supplied)

Salih, who is in his late twenties, says the idea for the photography workshops came from a trip he took with a friend to the city of Istasyon in 2017.

“It’s a very poor area and has never been reached by any humanitarian organization,” Salih tells Arab News. “We saw families from different backgrounds — Syrian, Iraqi, and Turkish. They speak the same language, whether Kurdish or Arabic, but they don’t talk to each other. We thought of using photography as a language. Analog photography can be like a key — a way to empower and bring together many communities in one place.”

While Sirkhane has a few centers around the province, it is its caravans — which drive out to small towns and villages without any such cultural centers — that have made perhaps the greatest impact in the lives of child refugees, eliciting the same joy and curiosity as an approaching ice-cream truck.

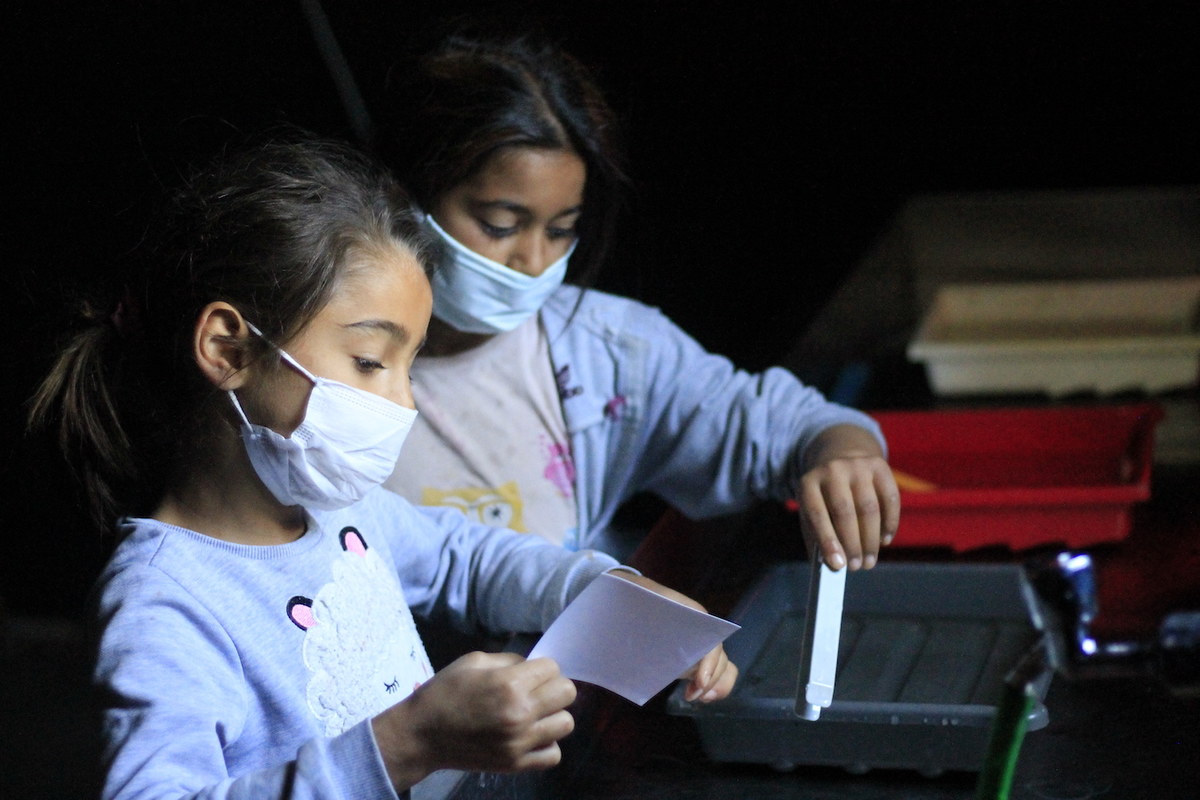

Printing inside darkroom. (Supplied)

Inside the darkroom-like caravans, Salih teaches the children how to handle negatives and develop and print photographs the old-fashioned way. The children are given simple compact cameras and, for a couple of weeks, are free to photograph whatever they like, including sensitive subjects such as child marriage and child labor.

“I show them all kinds of cameras — digital and analog. After that, I teach them composition,” Salih explains. Such a detailed activity can, in one way or another, grant children a sense of confidence and possibilities, especially the girls.

“Often, parents would say that girls (shouldn’t) participate in the workshop. Just boys. But after seeing that the girls are talented, they’ve started supporting and believing in them.” Most of the children will likely never have held a camera before, so they are amazed by what it can do through the click of a button. “Their first reaction is that they think it’s like magic,” remarks Salih.

A selection of the children’s black-and-white snapshots are currently being shown by Gulf Photo Plus (GPP) in Dubai’s Alserkal Avenue as part of its “Chemistry of Feeling” exhibition, which runs until September, displaying works that highlight the resurgence of analog photography. Photographers from all over the world submitted nearly 100 images.

More than 3,000 youngsters in the Mardin Province have so far participated in Sirkhane’s various programs. (Supplied)

“The children were very happy,” Salih said. “They’ve never heard of Dubai, but it’s great to see the pictures in an exhibition in the Arab world.”

“Sirkhane,” reads a label at the exhibition, “is based in a region where it is difficult to be a child.” And yet, looking at the pictures, there’s something innocent, pure and universal about them. Two boys are photographed playing football, two girls are holding their cameras, a group of boys take a selfie, and a girl wanders in a field in the far distance.

In an age where digital cameras, filters, and instant gratification rule, what makes shooting on film appealing?

“The anticipation is thrilling, waiting to see your work unfold,” said the Emirati artist Lamya Gargash in a GPP post on Instagram. “It’s not instant and that’s what I love most about it. Patiently you wait to see your vision and feel it’s come to life.”

Some of the children’s shots are out of focus or grainy, with white flash spots, but ultimately that simply adds to their intimacy, charm, beauty and humanity. (Supplied)

Salih says it helps children gain experience and go with the flow.

“When you give a digital camera to a child and he doesn’t think it’s a great photo, he will delete it (immediately). With analog photography, he’s just shooting photos and doesn’t know what will happen. But after seeing the results, he, or she, becomes self-confident,” he said.

The pictures from Sirkhane Darkroom bear little resemblance to the glossy, perfectly edited images we are most-accustomed to today. They are reminiscent, in a way, of Dorothea Lange’s powerful photographs of the Great Depression during the 1930s. Some of the children’s shots are out of focus or grainy, with white flash spots, but ultimately that simply adds to their intimacy, charm, beauty and humanity.