JEDDAH: Deprived neighborhoods in Saudi Arabia’s coastal city of Jeddah are undergoing major redevelopment after decades of relentless urbanization led to a host of social, economic, and environmental issues.

Municipal authorities are clearing districts and squatter settlements where planners say substandard infrastructure, criminality, and disease are blighting the lives of roughly half a million people.

Saudi cities have historically benefited from the close attention and generous investment of the central government, evident in the provision of a well-maintained physical infrastructure and impressive skylines.

But investment has had to keep pace with a rapidly growing urban population. According to the Kingdom’s Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs, approximately 82.1 percent of the Kingdom’s total population now lives in urban areas.

This trend is part of a global phenomenon, driven by a host of economic and environmental factors. According to UN-Habitat, around 60 percent of the global population will live in cities by the year 2030.

Current trends indicate that an additional 3 billion people will be living in cities by 2050, increasing the urban share of the world’s population to two-thirds. Some 90 percent of this urban growth is likely to occur in low- and middle-income countries.

In the context of cities like Jeddah, this has meant the rapid growth of densely populated and poorly planned urban districts that have swamped local infrastructure. In the words of Saleh Al-Turki, mayor of Jeddah since 2018: “Mistakes were made, ignored, and corruption occurred.”

According to an October 2017 paper published by Dr. Hisham Mortada, a professor of architecture at the College of Environmental Design at King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah, the city’s rapid population growth began in the 1970s during the Kingdom’s oil boom.

While Jeddah's substandard housing in some communities have provided an affordable starting point for many new arrivals, they are also seen as a breeding ground for criminality. (Supplied)

The paper, titled “Analytical conception of slums of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia,” traces the growth of the city’s slums to the demolition of the old city walls in 1947, which led to the creation of Al-Suhaifa, Al-Hindawiya, and Al-Sabeel.

“The districts later became an extension of old Jeddah and slums since they were built with poor construction materials and techniques and without planning,” the report said.

Other reasons given for the spread of Jeddah’s slums include an absence of state funding, a significant increase in property prices against falling incomes, and mass immigration, which by 1978 caused the city’s population to balloon to 1 million people — 53 percent of whom were foreign migrants.

Four decades later, with Jeddah’s population swelling to around 4 million, the old slum districts that had grown around the south and center of the city have expanded northwards.

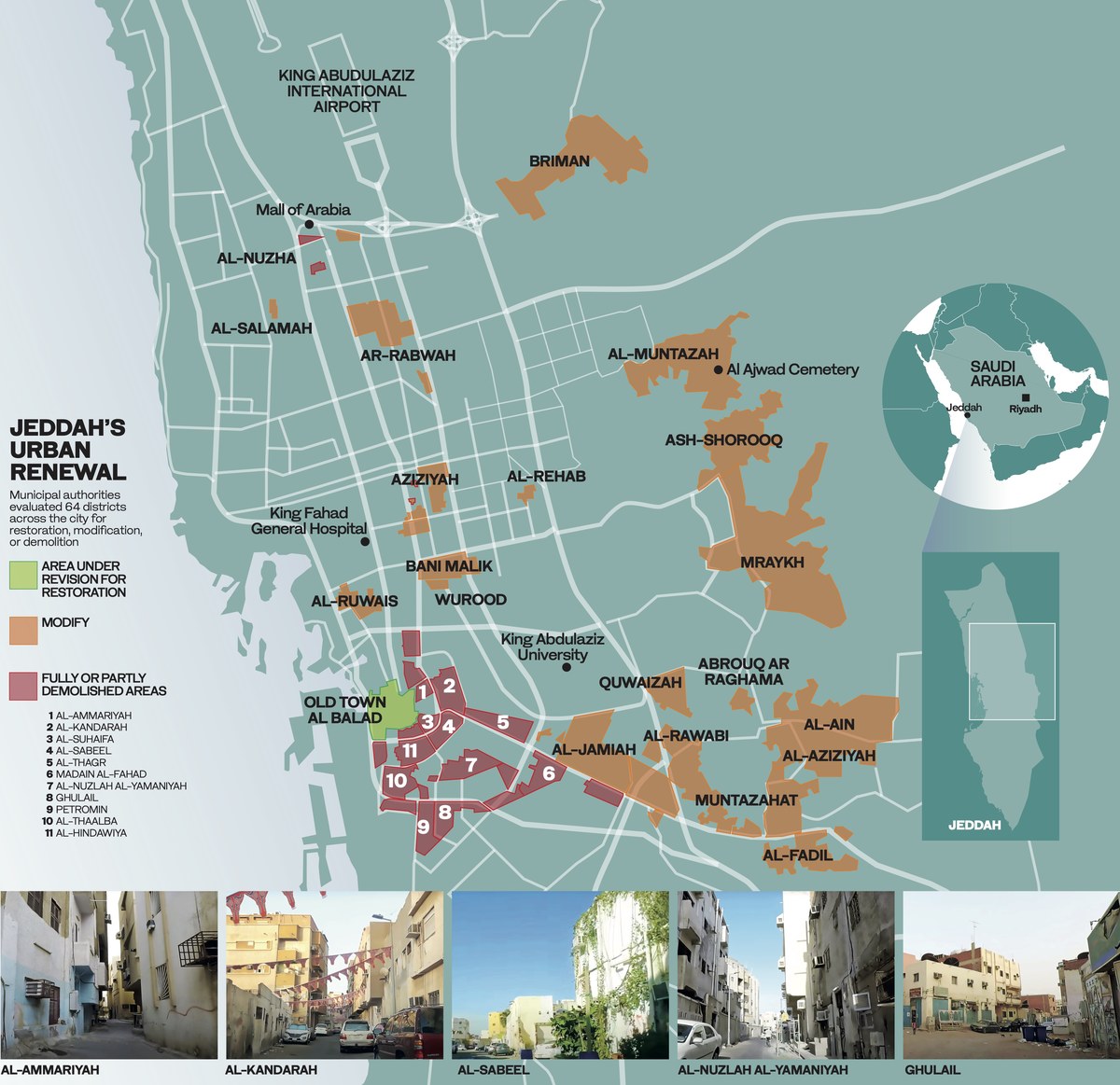

Determined to address the problem, the municipality announced plans late last year to demolish 64 districts across the city, including several associated with high crime rates and where illegal migrants had come to reside in densely packed communities.

Jeddah's Al-Kandarah district is one of the 26 districts considered undeveloped. (Supplied)

To date, the Jeddah Governorate’s Undeveloped Neighborhoods Committee has begun demolition work in 26 districts covering an area of 18.5 million square meters.

Eight of these districts are located within the lands of the King Abdulaziz Endowment for Al-Ain Al-Aziziyah, a charitable project established in 1948 to transport water to the city.

Municipal officials say the demolition work is due for completion by mid-November.

“The conditions in these areas are unfavorable,” Jeddah mayor Al-Turki told Rotana Khalijiya’s “Al-Soora” TV host Abdullah Al-Mudaifer in February. “It lacks security, there are no blueprints, its infrastructure is nearly non-existent, it is a den of crime. These are all facts.”

Those residents who hold the title deeds to their properties are being provided with free housing and compensation, Al-Turki said. To date, more than 550 families have been resettled, with 4,781 housing units to be allocated by the end of the year.

One of the municipality’s prime motivations for clearing these districts is the poor road access and the fire risk posed by the density of buildings.

While Jeddah's substandard housing in some communities have provided an affordable starting point for many new arrivals, they are also seen as a breeding ground for criminality. (Supplied)

“Given the tight spaces, it is difficult for vehicles to enter, never mind fire trucks, and today, the main concern to civil defense in Jeddah is the slums,” said Al-Turki. “If any fire erupts, it’s difficult to get through.”

Another motivation was the desire to clamp down on criminal activities. “The slums were a haven for human trafficking, a source of crime, and a place for thefts,” Maj. Gen. Saleh Al-Jabri, director of Makkah Region Police, said in the same TV interview.

“We’ve seized large quantities of drugs in a very short time. More than 218 kilograms was seized in these neighborhoods. These neighborhoods became central selling points for drug dealers. In some areas, they (are) publicly sold on these streets.”

Al-Jabri said drug dealers and human trafficking syndicates have long operated under the radar within the labyrinth of ramshackle neighborhoods. Crystal meth, a highly addictive drug known locally as Al-Shbo, is the most common narcotic sold in the slums.

In one recent bust, Al-Jabri said authorities were able to seize SR60 million ($15.9 million) in cash and more than 100 kilograms in gold worth SR50 million ($13.3 million) ready to be smuggled out of the Kingdom.

Jeddah's old slum districts have expanded northwards, such as in Al-Ammariyah, as the population swelled to around 4 million these past years. (Supplied)

Slums are extremely damaging to natural ecosystems and greatly increase the transmissibility of airborne, waterborne, and vector-borne diseases. Today, dengue fever, a prevalent vector-borne illness in Jeddah, costs the municipality SR150 million ($40 million) annually.

The issue was further highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which necessitated social distancing and self-isolation for those infected — measures that are near impossible to implement in overcrowded settlements.

Despite the clear benefits, slum clearance does carry negative social consequences. Thousands of people across several generations have long called these informal settlements home, establishing close-knit social networks with their neighbors that are not easily replaced.

And although housing in these communities is considered substandard, it is also viewed as an affordable starting point for many new arrivals in the Kingdom and those migrating from the countryside.

“Humans go through development phases just like cities,” Maha Al-Qattan, a Saudi sociologist, told Arab News.

“The closeness and ties between the people living within the slums are no different. People change, and it’s not like it was before when they would visit each other or call on one another. Today these slums are a convenience more so than a living place.”

Nevertheless, the socially corrosive effects of criminality in the slums has left authorities with little choice but to redevelop them from scratch. “They harbor dangers to society within the walls and outside,” Al-Qattan said.

With development work in full swing, Jeddah's numerous slum areas — such as Al-Jabeel — are expected to be transformed soon into vibrant economic and cultural hubs. (Supplied)

“Crimes will never cease, but it is essential to curb them by extracting the cancer that imposes pressure on communities and governments.

“These are ticking time bombs. The longer you keep them, the more difficult it will be to achieve the standards to upgrade the quality of life in cities.”

The decision to clear these areas is motivated by the desire to improve overall quality of life in the Kingdom’s cities, transforming them into vibrant economic and cultural hubs that are inviting to investors and tourists. It is also motivated by environmental concerns and the push towards greater sustainability.

The first studies on the condition of slums and their effect on the city’s development began in 1972, but plans to deal with them were repeatedly put off in favor of less disruptive initiatives to improve existing infrastructure, according to Al-Turki.

Now, thanks to the Saudi government’s commitment to raising overall quality of life in the Kingdom, under the umbrella of its economic and social reform agenda Vision 2030, urban redevelopment is back on track and far more ambitious in scope.

“Vision 2030 placed pressure on the Ministry of Municipal, Rural Affairs and Housing to elevate the quality of life, increase green spaces,” said Al-Turki.

“A green Riyadh, a green Jeddah, a green Middle East. All this would not happen in a city with weak infrastructure.”