RIYADH: Sustainable aviation fuel, made from products as diverse as used cooking oil and farm waste, could become a key tool in the airline industry’s drive to cut carbon emissions.

The commercial airline industry’s trade body, the International Air Transport Association, wants to hit net zero by 2050, and SAF may well help the sector get there.

SAF uses a variety of sustainable resources — that also include carbon captured from the air and green hydrogen — that can be mixed with traditional jet fuel “with no changes needed to the aircraft or infrastructure,” according to SAF producer SkyNRG.

It adds that the use of these green fuels cut emissions by between 70 percent and 80 percent per flight.

This is appealing to an industry which saw its 1,478 airlines account for 2.1 percent of all CO2 emissions and 12 percent of all CO2 output from the transport sector in 2019, according to the Air Transport Action Group. In that year, the industry spend $186 billion on 95 billion gallons of fuel to fly its passengers around the world.

Fossil fuel spending will remain a feature for this sector for some time. Commercial aircraft, like trains and heavy-goods vehicles, cannot rely on electric engines, as they do not provide the thrust these power-hungry vehicles demand.

In addition to this, the sector’s emissions are often singled out, as they make up a significant slice of a passenger’s annual carbon footprint, and also, mile for mile, flying is the most damaging way to travel for the climate.

All of this makes the aviation sector very interested in SAF. But there are problems.

While any aircraft that take standard jet fuel can use SAF, it costs twice much as using fossil jet fuel alone, according to UK oil giant BP’s Air division.

To force down the price of SAF, production needs to ramp up significantly. Currently, most SAF biofuel comes from waste fats or other agricultural byproducts, but their supply is well below what the aviation industry needs.

Airlines are slowly moving to adopt SAF, with Qatar Airways and Emirates airline among them.

Qatar Airways has said 10 percent of its flights will use SAF by 2030, while Emirates airline signed a memorandum of understanding with America’s GE Aviation in November 2021 to conduct an Emirates Boeing 777-300ER test flight using 100 percent SAF by the end of the year.

Pan-European planemaker Airbus has announced that all its aircraft are certified to fly with a mix of up to a 50 percent SAF blended with kerosene. The aim is that all of its planes will be able to fly solely using SAF by 2030.

IATA says the main challenge of SAF producers is meeting airline demand.

“I think quantity is the main issue at the moment,” Willie Walsh, IATA director general, told CNBC last February.

About 100 million liters of SAF were used last year, “that’s a very small amount compared to the total fuel required for the industry,” Walsh said.

Airlines have ordered 14 billion liters of SAF, which “addresses the issue of whether airlines will buy the product,” he added.

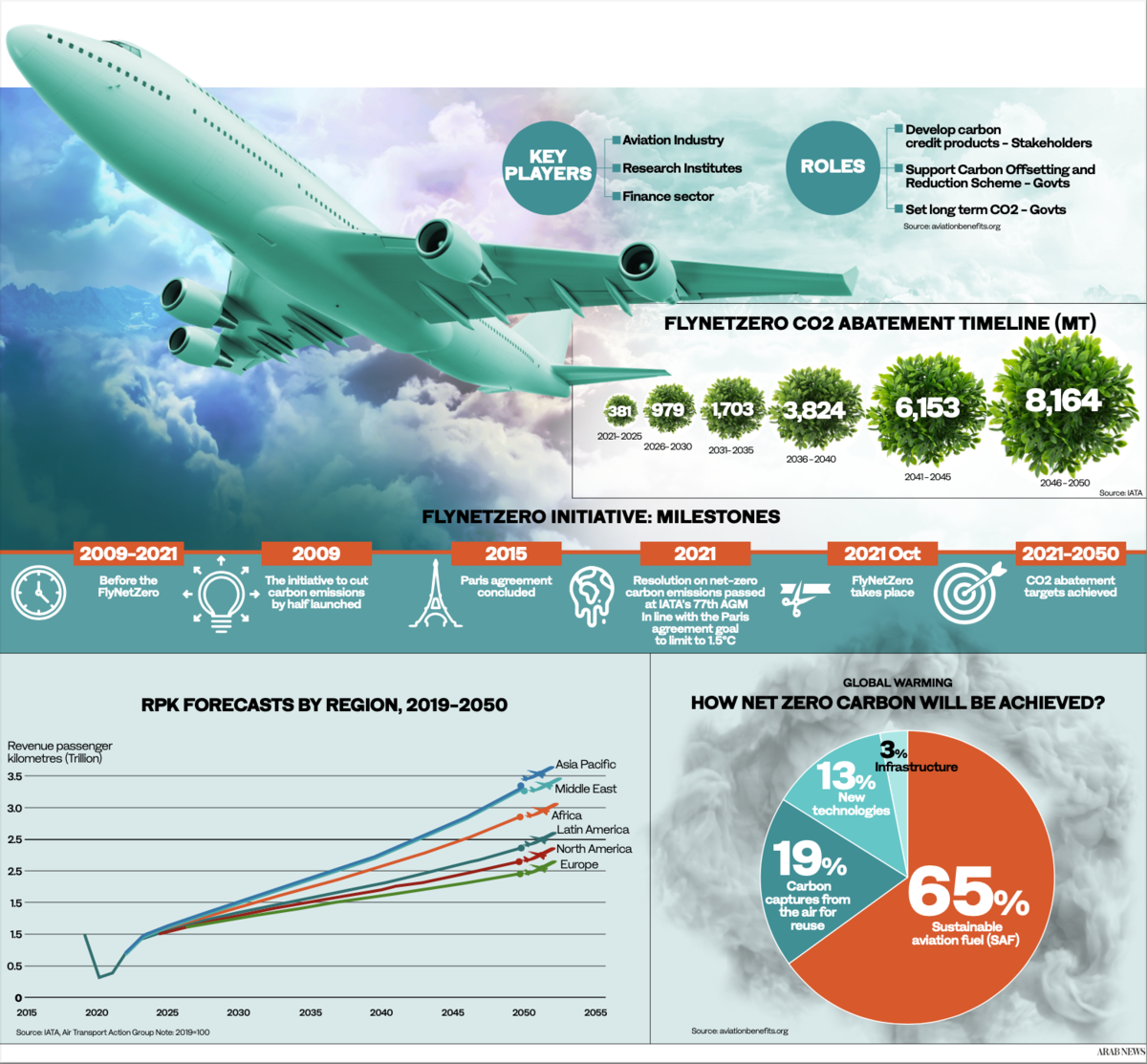

IATA expects to see SAF production hit 7.9 billion liters by 2025, this would meet only around 2 percent of the industry’s fuel requirements. But by 2050, the association says production would jump to 449 billion liters, or 65 percent of the sector’s needs.

SAF is “the only answer between now and 2050” Boeing’s CEO David Calhoun told CNN.

That may be true. But SAF’s production base is going to have to expand greatly in a short time. At the moment it is using a thimble to fill a well.