LONDON: To the bedouin, the mysterious structures of uncertain age and unknown origin scattered across the harsh and dramatic landscapes of northwestern Saudi Arabia have always been simply the works of “the old men.”

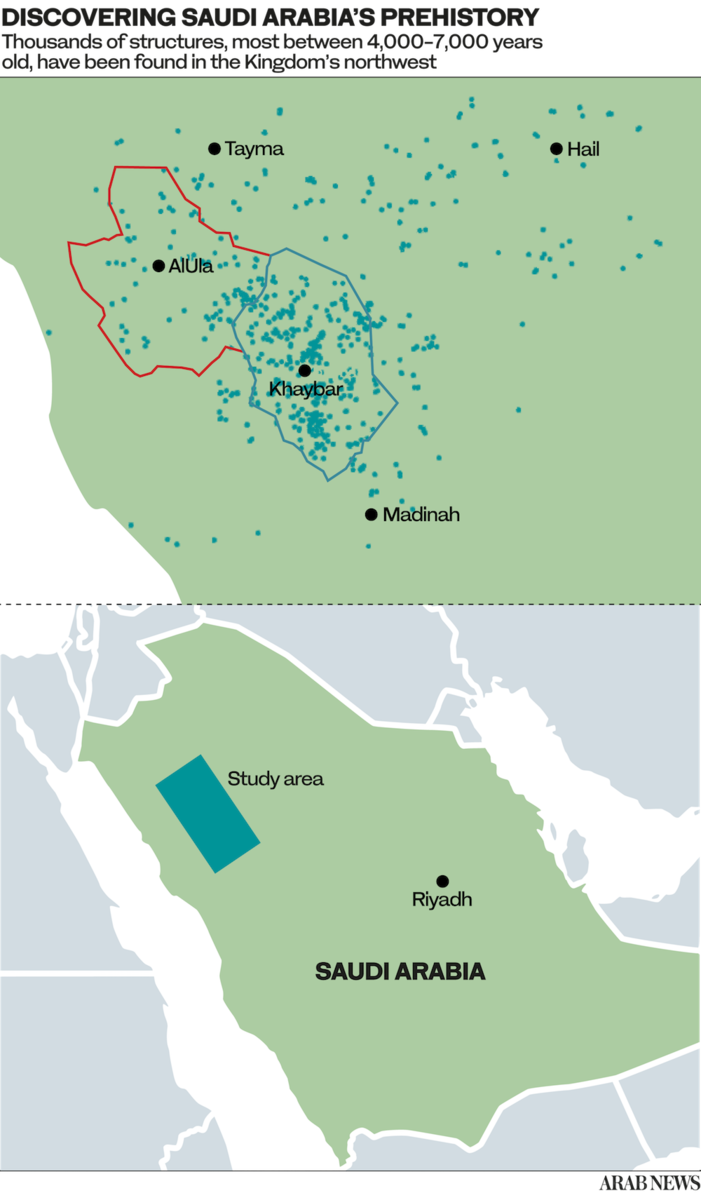

To the archaeologists who have just completed a four-year project to catalogue all the visible archaeology of AlUla County and the nearby Harrat Khaybar volcanic field, the tens of thousands of structures they have found, most between 4,000 and 7,000 years old, are the key to a radical rethinking of the prehistory of the Arabian Peninsula.

“A lot of the archaeological focus in the region in the past has been on the Fertile Crescent, running through Jordan, Israel and up into Syria and beyond, and little archaeological attention has been paid to this early material of Saudi Arabia,” said archaeologist Dr. Hugh Thomas, a senior research fellow at the University of Western Australia.

“But as we do more and more research, we’re realizing that there was so much more here than small, independent, communities living on nothing much and not doing much in an arid area.

“The reality in that in the Neolithic period these areas were significantly greener, and there would have been really sizeable populations of people and herds of animals moving across these landscapes.”

In the near future, he believes, “I think we are going to make massive discoveries that are going to change how we view the Middle East completely.”

Dr. Thomas is co-director of the Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia project, set up in 2018 by the Royal Commission for AlUla, as part of the Identification and Documentation of the Immovable Heritage Assets of AlUla program. The following year the project was expanded to include the neighboring, heritage-rich region of Khaybar.

A “core” area of AlUla of 3,300 sq. m was surveyed separately by UK-based Oxford Archaeology. Working with staff and students of King Saud University in Riyadh, they identified more than 16,000 archaeological sites.

Setting out initially to survey the AlUla hinterland, an area of more than 22,500 square kilometers, Dr. Thomas and his colleagues faced a daunting task, which they broke down into three stages.

A remote preliminary survey of the entire area, using satellite imagery, was followed by aerial photography of selected sites and, finally, excavation of a small number of the most promising structures.

The first stage lasted more than a year, with team members poring painstakingly over Google Earth and other satellite imagery and pinning every structure they spotted.

For the University of Western Australia team back in Perth, it meant “hour after hour of patiently scrolling through,” Dr. Thomas said.

“Sometimes it was in areas where there was absolutely nothing, just endless kilometers of remote desert. But then at other times you’d find structures all over the place, and you would get through only a few kilometers in a session, because you were constantly finding and pinning new archaeological sites.”

The hard work paid off handsomely.

By the end, they had identified 13,000 sites in AlUla and an extraordinary 130,000 in Khaybar county, dating from the Stone Age to the 20th century. They logged everything they saw, including some of the remains of the Hejaz railway, built by the Ottomans before World War I, but the vast majority of the sites dated from prehistory.

Each site consisted of anything from one structure to clusters of 30 or more, and they have now catalogued more than 150,000 individual structures of archaeological interest, especially in the Khaybar region, where there is “a really dense, significant concentration of archaeological remains.”

After the remote sensing came the really fun part — flying low over the spectacular landscapes of AlUla and Khaybar in helicopters, using open-door photography to record sites previously identified by the satellite survey as being of particular interest.

The pilots, from the Saudi-based The Helicopter Company, flew from site to site along flight paths created by the archaeologists.

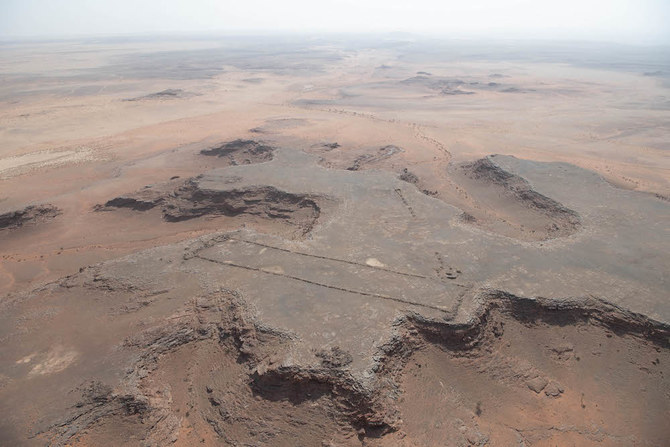

Archaeological discoveries in AlUla and Khaybar are the key to unlocking the secrets of prehistoric Saudi Arabia. (Moath Alofi)

“They were commercial pilots who at first had no idea about the archaeology,” Dr. Thomas said. “But they were very keen, and also pretty good at interpreting and spotting things.

“They ended up having a really great understanding, and that was so beneficial to the project. I could say, ‘I’m after three funerary pendants up on an outcrop’, and the pilot would say, ‘Oh, I can see them, in front of us,’ and they’d steer the helicopter round to give you the best photographic angle.”

By the end, he said, “some of the pilots would have seen more archaeology up close than the majority of archaeologists.”

The last aerial photography was carried out in March this year and, by then, the team had captured more than a quarter of a million images across AlUla and Khaybar.

Among the structures they photographed were more than 350 examples of one of the most extraordinary types of large-scale structures scattered across Saudi Arabia’s prehistoric landscape — the mysterious mustatil.

Mustatil is the Arabic word for rectangle, and these often huge, rectangular structures, built by an unknown people more than 8,000 years ago, may be unique to the Arabian peninsula.

More than 1,600 are now known to exist across 300,000 sq. km of northwestern Saudi Arabia, concentrated mainly in the vicinity of AlUla and Khaybar.

Mustatils vary in type — some are more complex than others — but usually they consist of two parallel walls, or occasionally more, joined at either end by shorter walls to create a rectangle. They range in length from 20 to 620 meters and often they are clustered together, in groups numbering anything from two to 19.

Of the 1,600 mustatils identified via satellite imagery and the 350 photographed from the air, 39 were selected for ground survey by Thomas’ team. (Rebecca Repper)

In some places, mustatils have been “overbuilt” by subsequent generations who have constructed circular ringed tombs, or so-called pendant tombs, on or very near them.

Building some of the mustatils would have been a big commitment for a considerable number of people. The largest structure ground-surveyed by the AAKSA team, situated on the Harrat Khaybar lava field 50 km south of Khaybar town, was built from basalt boulders and measures 525m in length.

It is estimated that the structure weighs about 12,000 tons, with individual stones weighing between 6 and 500 kg.

Extrapolating from experimental studies carried out on Mayan structures in Guatemala, the archaeologists have estimated that it would have taken a group of 10 people two or three weeks to build a mustatil more than 150m long. Larger structures, up to 500m, could have been constructed by a group of 50 people in about two months.

As Dr. Thomas and his colleagues wrote in a paper published recently in the journal “Antiquity,” not only are mustatils “an important component of the ancient Arabian cultural landscape,” they are also among the earliest stone monuments in Arabia, and “globally one of the oldest monumental building traditions yet identified.”

Of the 1,600 mustatils identified via satellite imagery and the 350 photographed from the air, 39 were selected for ground survey by Thomas’ team. Of these, just a handful were excavated, and these have revealed a wealth of previously unknown information.

In late 2018 and 2019, for example, archaeologists from both the UWA and Oxford teams began excavating undisturbed mustatils east of AlUla valley, and discovered evidence that the structures had served a ritual purpose. Collections of horns and other cranial bone fragments, from animals including cattle, goat and gazelle, were found in chambers in the structures, which could suggest offerings had been made to some long-forgotten deity.

“These are ritual structures, I’d bet my house on it,” Dr. Thomas said.

“We have now excavated five of them, the Oxford Archaeology team has excavated three, and other teams are excavating others too. With the artefacts that are inside, and also the construction techniques that are involved in creating them, there is no practical function for these structures, other than ritual, that would make any sense.”

In addition to Mustatils, there are an estimated 917 kites around Khaybar built in varying shapes and sizes and some dating back to between the fifth and seventh centuries B.C. (Moath Alofi)

There is no roofing, the walls are too low for them to have been used for keeping animals in them, and some of them are built on the slopes of mountains that are incredibly steep and difficult to walk up.

Organic remains can be carbon-dated, and the animal bones revealed that the site was late Neolithic – about 7,000 years old. In the past season, however, in a collaboration with the archaeology department at Durham University in the UK, the team has been employing another sophisticated dating technique called Optically Stimulated Luminescence.

This, Dr. Thomas said, “basically allows you to date the last time that sand had light fall directly upon it, which is a really useful technique for dating structures that don’t have any kind of organic deposits within them.”

So far, nothing has been unearthed to suggest why the mustatils were built where they were.

“In some of the locations where we find them we just can’t understand why they were built there,” Dr. Thomas said.

“They might be in a random valley with seemingly not much happening around them. It suggests that people are coming to that spot, creating them, then moving on and probably coming back periodically.”

That, of course, poses the question: what was so special about these sites to these people?

Another, possibly connected, mystery is that the mustatils and even the later Bronze Age burial structures in the region were clearly built to be appreciated not from ground level, but from up above, in the sky.

“What’s fascinating is when you see them from the ground, they’re not that spectacular, just a series of walls,” Dr. Thomas said.

“But as soon as you get in a helicopter, or you look at it on satellite imagery, these things just come to life.”

One theory is that the structures might have been built to be viewed from above by the dead. Another possibility is that they were ritual structures constructed for the benefit of some deity in the sky.

But, as the structures were built long before human beings developed writing, the truth is likely to remain a mystery.

Equally mysterious is where the people came from who built the mustatils — and where they ended up. As yet, no Neolithic burial sites from the same period have been found.

Archaeologist Don Boyer measures a tower of stones next to a 525m long Mustatil in Khaybar. (David Kennedy)

“The hope is that, in the future, we might identify some Neolithic burials,” Dr. Thomas said. “But the reality now is that we’re not sure where the people of the Neolithic are.”

They could have been buried in unmarked graves at random sites, which would make it very hard to find any of them.

“Alternatively, there may be other things that they did to their bodies, which means that we will never find them.”

However, a series of finds in some mustatils has hinted at a perhaps macabre practice in about the mid-fifth millennium BC. Some human remains have been found — but only fragments.

“In one, we found part of a foot and five vertebrae and a couple of long bones. We can tell that while there was still soft tissue attached and holding the bones together, fragments of that body were taken and placed within this mustatil, or next to it.”

There are, however, multiple burial sites in the region — and sometimes close to mustatils — from the Bronze Age, dating from about 2,500 years later.

“There are thousands upon thousands of tombs, pendant burials and larger monumental tombs in the region, indicating that there were large, thriving populations here,” Dr. Thomas said.

The most dramatic examples are located in Khaybar county, to the southeast of AlUla.

“Projecting out of Bronze Age oases are these long pathways, funerary avenues, flanked by thousands of tombs, creating a really significant funerary landscape.”

The next objective for the team is “to focus on this shifting idea of monumentality. In the Neolithic period, for whatever reason, something occurred that meant that people started creating these absolutely massive ritual structures, over a 300 to 500-year period.

“Then it stopped. Archaeologically, from about 4,800 down to about 2600 BC, we find very little — some domestic structures, but not many graves.

In addition to the mustatils, the site has kites whose geometric shapes may be connected or unconnected to each other. They may be part of a building or separate, or stone piles. (Duhim Alduhim)

“Then suddenly these monumental burials start appearing across the landscape. Why this shift from the mustatil, monumental ritual structures, to the focus 2,000 years later on the individual, or family groups, that were being buried in these structures?

“What happened in those few thousand years?”

Whatever the answer, the vast number of mustatils identified — about 1,600 in an area roughly the size of Poland — not only puts Saudi Arabia’s ancient past in a Neolithic class of its own, but has global repercussions.

“When we look at Neolithic landscapes across the world, often you’re only finding a handful of structures, less than a dozen,” Dr. Thomas said.

“So to have something like the mustatil, where you’ve got well over 1,000, covering such a significant area, really changes how we have to view the Neolithic.

“It indicates that the Neolithic is much more complex than we originally thought.

“And, as more research comes out about the mustatil, I think that will completely revolutionize how we view Neolithic societies, not just in Arabia but across the rest of the world.”

There will be 12 archaeological teams at work in the field this autumn, exploring the past cultures of AlUla and Khaybar from prehistory to the early 20th century. Stone structures of the late prehistoric period will remain a key focus.