SAO PAULO, BRAZIL: The 15th-best tennis player in the world, Brazilian Beatriz Haddad Maia, left the US Open on Sept. 4 after she and her Kazakh partner Anna Danilina were defeated by the duo Nicole Melichar-Martinez and Ellen Perez.

Nevertheless, Brazilians have developed a growing devotion to Maia, and many hope she can become the best tennis player in the country’s history.

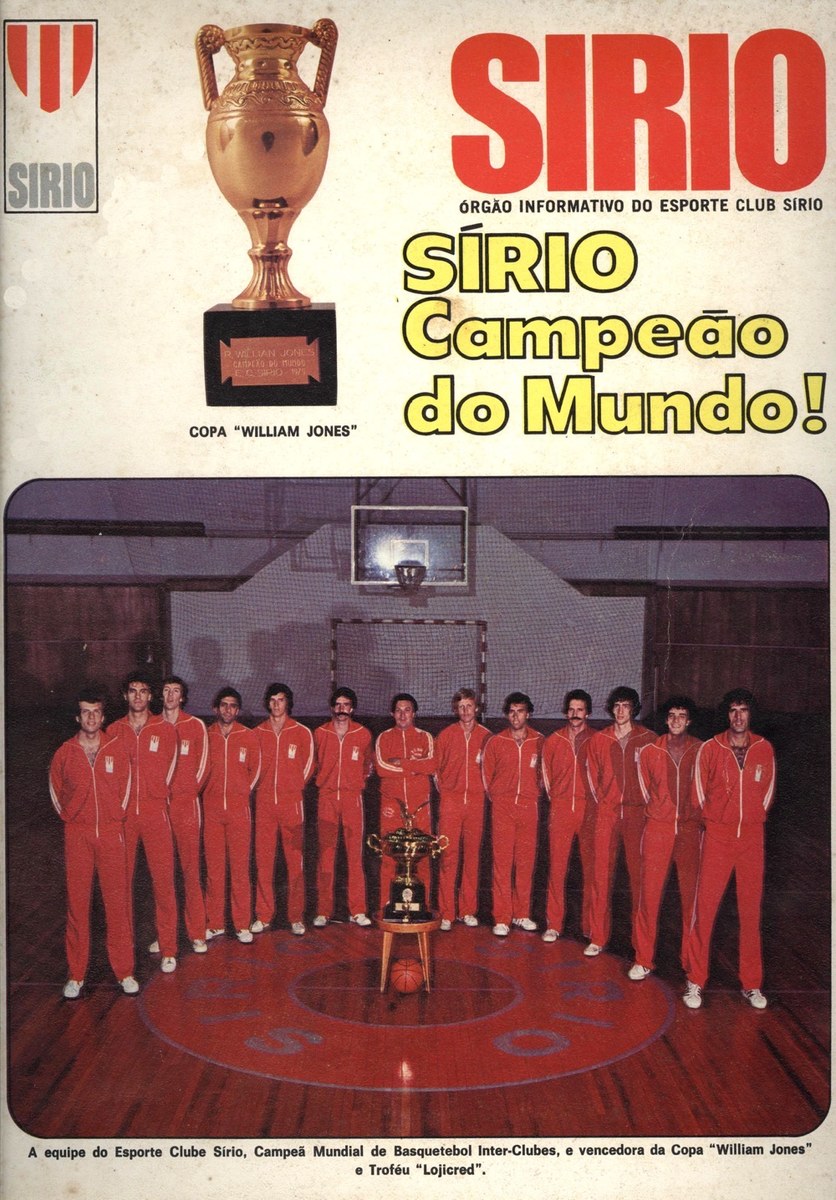

Part of her success comes from her formative years at Esporte Clube Sirio, a leading sports and social club in Sao Paulo, Brazil’s major financial hub.

Founded in 1917, the club is one of the great examples of the Arab community’s contribution to sports in Latin America.

Esporte Clube Sirio, a sports club with strong connections to the Arab community in Sao Paulo, helped develop the skills of tennis star Beatriz Haddad Maia. (AFP)

Its first complex included four tennis courts, a basketball court, a football pitch and a lake.

The number of members grew very rapidly over the years among Syrian and Lebanese immigrants — such as the Haddad family — who formed a large community in Sao Paulo, and the club became wealthy. Non-Arab Brazilians soon began to join too.

By 1949, Sirio had gained a reputation as one of the top sports clubs in Sao Paulo, and moved to its current location, in the southern zone of the city, building a modern complex from scratch.

“I joined Sirio as a child in 1955. I saw most of it being built,” Washington Joseph, 72, known by the nickname Dodi, told Arab News. “My brother and I began practicing football, then gymnastics and judo. At 11, I began playing basketball.”

Between 1967 and 1982, Dodi, the grandson of Syrian and Lebanese immigrants, was one of the greatest basketball players in Brazil, and was part of the mythical squad that conquered the world championship in 1979.

Between the 1950s and 1980s, Sirio was one of Brazil’s major basketball teams. Many of its players were regularly called to play in the national team, which was one of the world’s best at the time.

In 2014, Palestino decided to include on its jersey the full map of Palestine (before the partition), replacing the number one. (Supplied)

“We had a hegemony of about 30 years. We won several national tournaments, and also the South American championship six times,” Dodi said.

Another Arab club, Sao Paulo’s Monte Libano, also had a very competitive basketball team.

Sirio took part in the Intercontinental Cup six times, and Dodi was part of the team in all of them except for the 1984 edition. “We ended up in third place twice, second place twice and won it once, in 1979,” he said.

That year, the cup was hosted by Brazil. The matches drew thousands of basketball fans to the stadium and were televised nationwide.

Sirio made it to the final against the Yugoslav club Bosna. The Brazilians’ spectacular 100-98 victory has never been forgotten.

“Our generation greatly helped to popularize basketball in Brazil,” Dodi said. Sirio continued to be a leading basketball club until 1995, when the sport became largely professional in Brazil and its directors concluded that it would no longer be possible to keep the necessary level of investment necessary to maintain it at the top.

A closeup of jersey featuring a map of palestine. (Supplied)

But Sirio never ceased to be a school for new athletes. It had great champions such as the weightlifter Tamer Chaim — who competed at the summer Olympics in Munich — and tennis player William Kyriakos.

“We also had great judo fighters and top handball and volleyball teams. We continue to be an authority in sports,” Dodi said, adding that a frequent rival of Sirio was Club Deportivo Palestino of Santiago, Chile.

Carlos Medina Lahsen, a Chilean of Palestinian descent and an expert in Palestino’s history, told Arab News: “Especially in the 1950s, matches between the two clubs were greatly anticipated.”

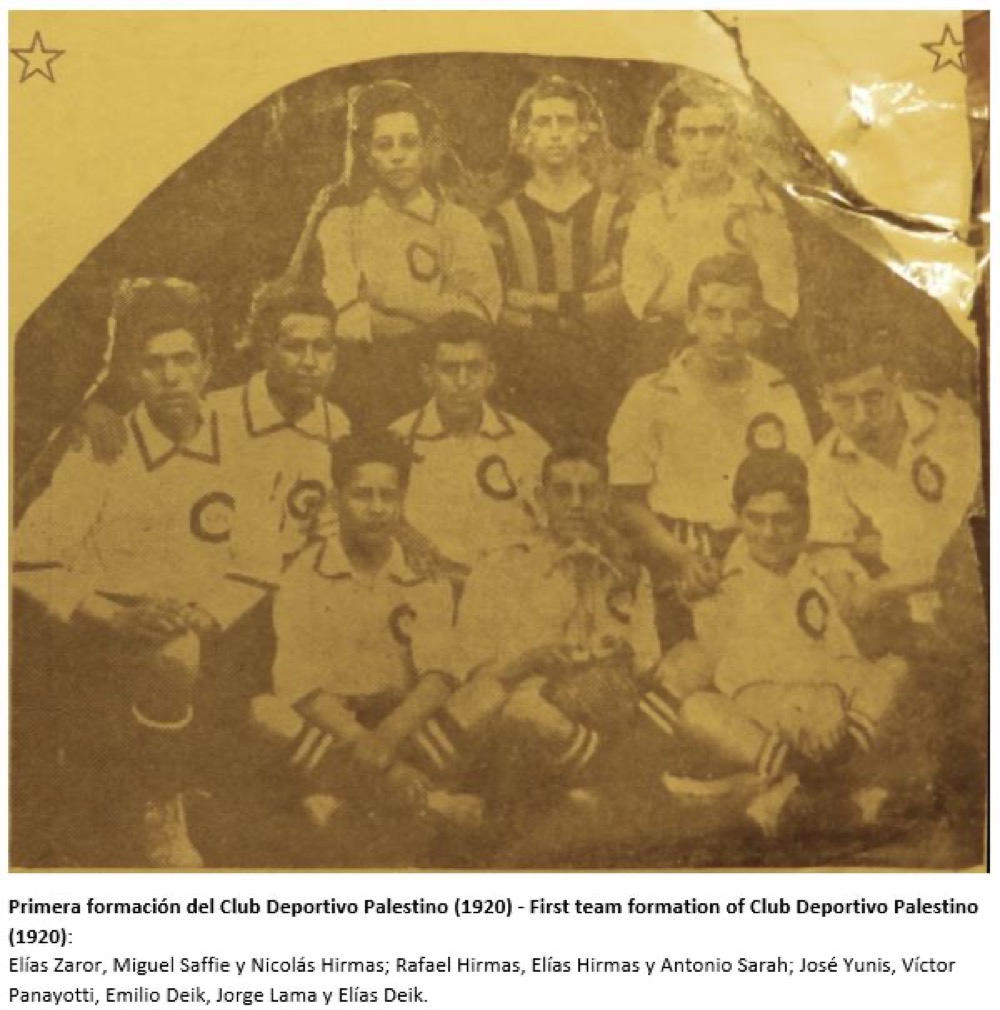

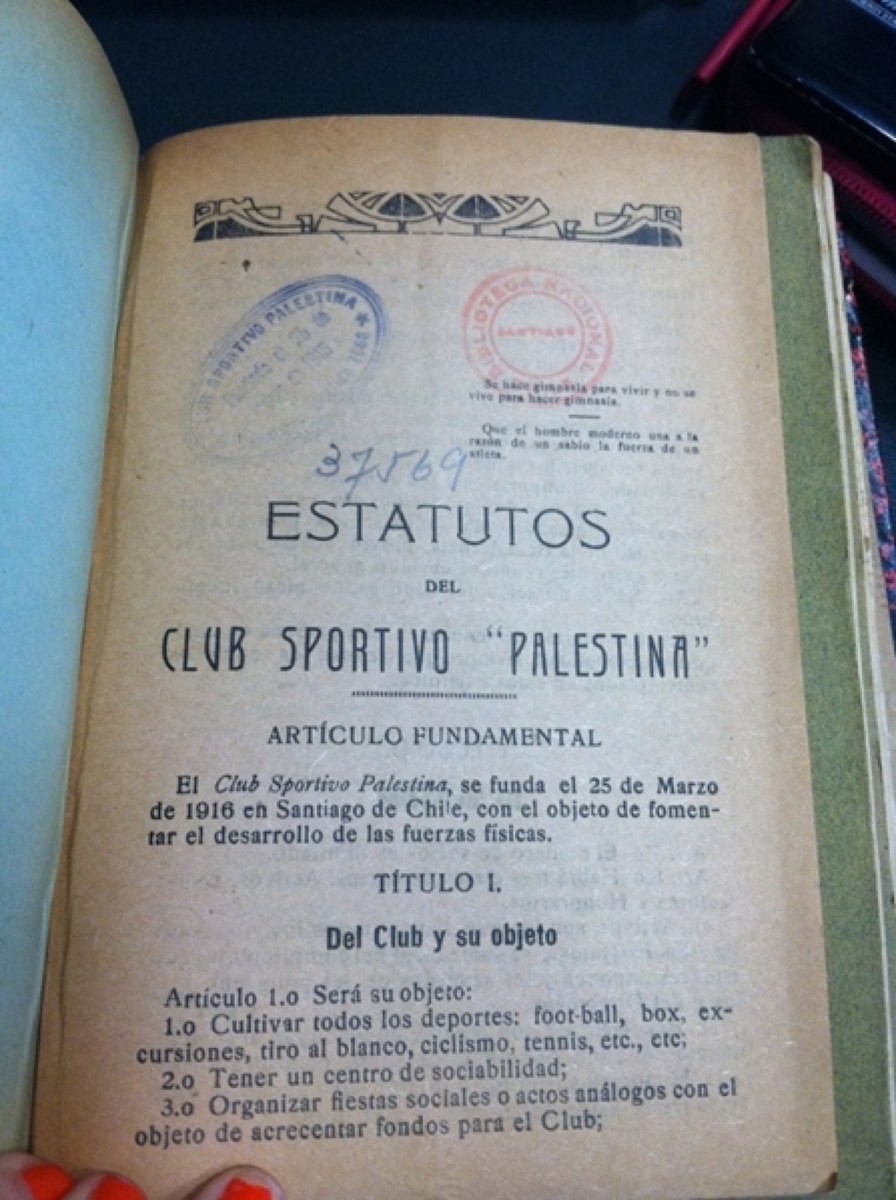

Palestino was founded in 1920 as a football club. Due to British influence, Palestinians already played football in the Middle East before migrating to Latin America, Medina Lahsen said.

“Communities of foreigners began to practice sports looking for integration into Chilean society, but discrimination was very intense at that time,” he added.

The club gave up on football in 1923 and prioritized tennis. But Palestino and another Arab club joined forces in the 1940s, and resumed football at the time of the 1947 partition of Palestine.

Sirio’s 1979 Intercontinental Cup-winning Basketball team. (Supplied)

During the 1950s, the team received much investment from Palestinian businessmen and became known as “the millionaires.” In 1955, it conquered the national football championship.

With the second uprising against Israeli occupation (2000-2005), the interest of many Palestinian Chileans in Palestino grew, and the club saw a surge in new fans.

In 2008, Palestino made it to the final of the national championship against Colo Colo. Although Palestino was defeated, it garnered widespread attention from Palestinians.

In the internet era, news of a football club named after their country amazed them. “We heard that people rented cinema theaters and streamed the match in the Gaza Strip,” said Medina Lahsen.

From then on, the connection between the club and Palestine greatly increased. Chilean players visited Palestine on many occasions, and even the main team took part in matches there. The Bank of Palestine became a frequent sponsor.

In 2014, Palestino decided to include on its jersey the full map of Palestine (before the partition), replacing the number one.

This spurred controversy in Chile, with members of the Jewish community accusing the club of erasing Israel from the map, and many pressuring the national football federation to intervene.

The sports authorities did not consider the symbol to be political in nature, and only fined Palestino because the map exceeded the maximum area of the jersey that could show printed content.

“The club used that jersey all through the season. Until now, it’s the most popular jersey in Palestino’s history,” said Medina Lahsen.

The documentary film “4 Colores,” which narrates the club’s history, demonstrates how football promoted a connection between Chileans and the Palestine cause.

“Many of Palestino’s fans aren’t directly part of the Arab community in Chile, but nevertheless they’ve been touched by the plight of Palestinians worldwide,” said Medina Lahsen, who was in charge of research for the film.

He discovered that across Latin America there have been sports clubs with Palestino or Arabe in their name, such as Central Palestino in Uruguay and Palestino Futbol Club in Honduras. In Argentina and Chile, there are dozens of clubs named Sirio or Sirio Libanes.

In Panama, one of the top football clubs is Deportivo Arabe Unido, from the city of Colon.

Sirio’s unforgettable and decisive game against Bosna that clinched the championship. (Supplied)

Although the Arab community in Colon is not very large — it has an estimated 120 families — it has played a central role in local sports.

DAU “was founded by Arab Panamanians in the 1990s, when the country didn’t have a professional football league. We never thought it would grow so much,” the club’s President Mohamed Hachem told Arab News.

Since its creation, the club has been one of the most successful in Panama’s premier league, with several national championships. Most of its fans are not members of the Arab community now.

“We’ve had a few players of Arab origin, and the Arab community is very supportive of us,” Hachem said.

The club is working to build its new headquarters and sports center, including a social area.

One of Hachem’s plans for the future is to promote a championship among Arab football clubs in Latin America. “It would be a beautiful thing to gather all of them,” he said.