LONDON: Although Syria remains in a precarious state just days after the fall of the regime of Bashar Assad, hundreds of displaced Syrians have flocked to border crossings in Lebanon and Turkiye, eager to return to their homeland after more than 13 grueling years of civil war.

At daybreak on Monday, scores of people gathered at the Cilvegozu and Oncupinar border gates in southern Turkiye and the Masnaa crossing in Lebanon, confident for the first time in years that they would not face arrest or conscription when they reached the other side.

On Sunday, in a historic moment for the Middle East, a coalition of armed opposition groups led by Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham seized Damascus. Now a refugee himself, Assad fled the country and sought asylum in Russia, marking an inglorious end of his family’s brutal 54-year rule.

Syrians displaced across the Middle East, North Africa, Europe, and further afield by the years of fighting and persecution in their home country poured into the streets in celebration, jubilant that the uprising that began in 2011 had finally succeeded in dislodging Assad.

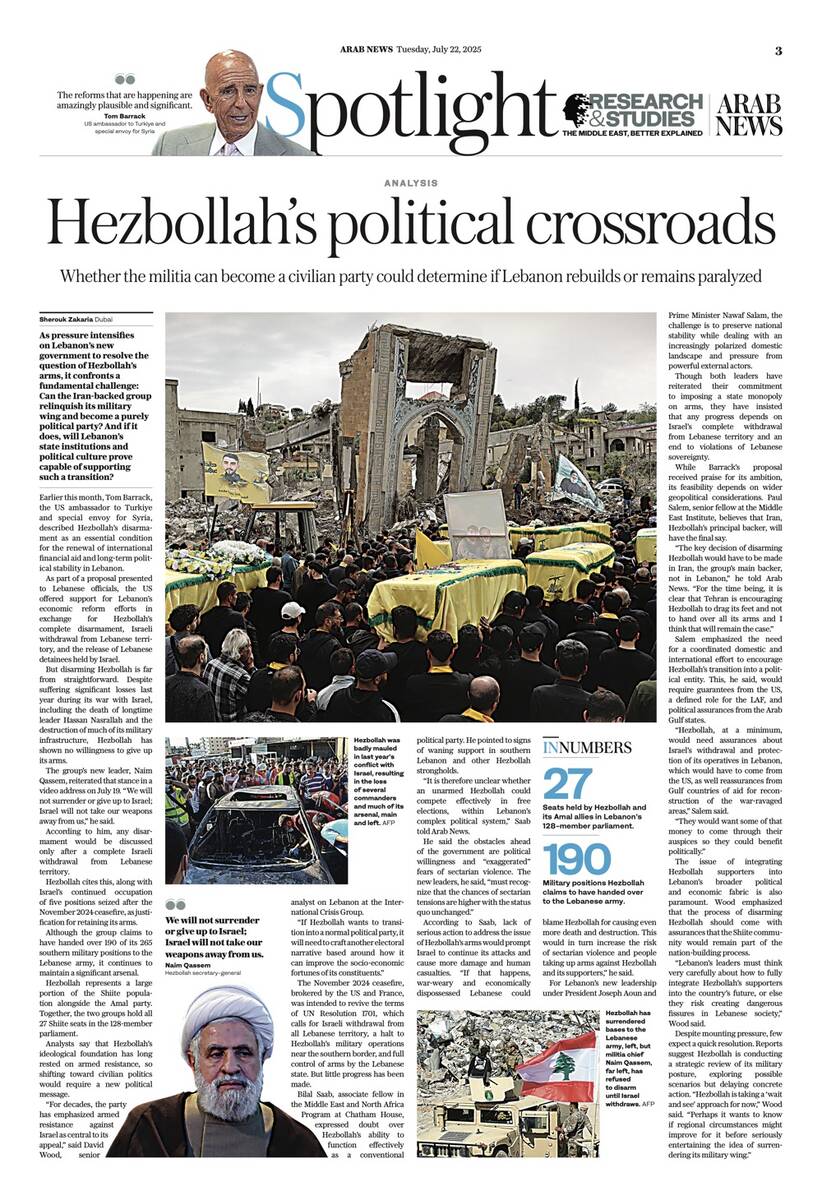

An aerial view shows long vehicle queues have formed on the roads leading to and from Damascus on December 8, 2024. (Getty Images)

Syria remains the world’s largest refugee crisis. Since the outbreak of civil war in 2011 following the regime’s brutal suppression of anti-government protests, the UN says more than 14 million Syrians have been forced to flee their homes.

While the majority sought refuge in other parts of Syria, including areas outside the regime’s control, others fled to neighboring countries — primarily Turkiye and Lebanon, but also Jordan, Egypt, and Iraq. Many more risked the perilous Mediterranean crossing to Europe.

Some 7.2 million Syrians remain internally displaced, where 70 percent of the population is deemed to require humanitarian assistance and where 90 percent live below the poverty line, according to the UN refugee agency, UNHCR.

More than 5 million Syrian refugees live in the five neighboring countries — Turkiye, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt. Turkiye alone hosts around 3.2 million registered with the UNHCR, while Lebanon hosts at least 830,000.

Karam Shaar, a senior fellow at the Newlines Institute for Strategy and Policy, a nonpartisan Washington think tank, believes the first Syrians to return are likely “the most vulnerable,” such as those in Lebanon and in Turkiye, who have endured poverty and mounting hostility.

“In general, because of the situation in Lebanon and Turkiye being so bad, I think these people would be the most likely to come back,” Shaar told Arab News. “Many of them would be willing to go back to the rubble of their houses as long as Assad is not there because it just can’t get any worse.”

In Lebanon, anti-Syrian sentiment has grown significantly since the country was plunged into a debilitating economic crisis in 2019. There have even been cases of violence against members of the community and their property.

In April, Syrians were attacked and publicly humiliated in the streets of Byblos after a senior Lebanese Forces official, Pascal Suleiman, was reportedly killed by a Syrian gang during a botched carjacking.

On Monday, scores of people gathered at the Masnaa crossing in Lebanon. (AFP)

Compounding the plight of Syrians, the recent Israeli assault on Lebanon has displaced many families already struggling to survive, forcing them to live on the streets amid reports they have been denied access to municipal shelters.

Even before the outbreak of fighting between Israel and Hezbollah, displaced Syrians were subjected to restrictions on work and access to public services. Some 90 percent of them lived in extreme poverty, according to the UN.

Returning to Syria while Assad remained in power was out of the question for many. Before the regime’s downfall on Sunday, Human Rights Watch warned that Syrians fleeing Lebanon risked repression and persecution upon their return, including “enforced disappearance, torture, and death in detention.”

Indeed, the Syrian Network for Human Rights documented at least nine arrests of returnees prior to Oct. 2, most of which were reportedly linked to “mandatory and reserve” military conscription.

Syrian and Lebanese people celebrate the fall of the Syrian regime on December 8, 2024, in the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli. (AFP)

In Turkiye, Syrians have frequently been scapegoated by politicians. In July, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan accused opposition parties of fueling xenophobia and racism. His remarks came a day after anti-Syrian riots broke out in the Kayseri province after a Syrian refugee there was alleged to have sexually assaulted a 7-year-old Syrian girl.

A similar wave of violence erupted in an Ankara neighborhood in 2021 after a Turkish teenager was stabbed to death by a group of young Syrians. Hundreds of people took to the streets, vandalizing Syrian owned businesses.

Erdogan announced on Monday that Turkiye was opening its Yayladagi border gate with Syria to facilitate the safe and voluntary return of refugees, Reuters reported. Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan said his country would support the return of Syrians to contribute to the reconstruction of the conflict-ravaged country.

“Those with families in Syria are eager to at least pay them a visit,” Marwah Morhly, a Turkiye-based media professional, told Arab News.

“Many are making plans to visit their hometowns with their children, who were born in Turkiye and have never been to Syria or met their relatives in person.”

Children walk in a camp for Syrian refugee in Turkiye set up by Turkish relief agency AFAD in the Islahiye district of Gaziantep on February 15, 2023. (AFP)

However, given the ongoing insecurity and political uncertainty in Syria, and the fact that many Syrians have built lives in Turkiye, the decision to return is not an easy one to make.

Morhly herself is hesitant about visiting, despite longing for her hometown of Damascus. “I can’t take a risk with a young child,” she said, referring to her son. Such a decision would depend on a Syrian-Turkish agreement on the refugee issue, she added.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi said “there is a remarkable opportunity” for Syrians “to begin returning home.”

“But with the situation still uncertain, millions of refugees are carefully assessing how safe it is to do so. Some are eager, while others are hesitant,” he added in a statement on Monday.

Syrians in Turkiye celebrate the fall of Assad in Gaziantep, on December 8, 2024. (AFP)

Urging “patience and vigilance,” he expressed hope that refugees would be able to “make informed decisions” based on developments on the ground. Those decisions, he added, would depend on “whether the parties in Syria prioritize law and order.”

He stressed that “a transition that respects the rights, lives, and aspirations of all Syrians — regardless of ethnicity, religion, or political beliefs — is crucial for people to feel safe.”

UNHCR “will monitor developments, engage with refugee communities, and support states in any organized voluntary returns,” he added, pledging to “support Syrians wherever they are.”

Grandi also highlighted that “the needs within Syria remain immense,” as more than 13 years of war and economic sanctions had “shattered infrastructure.”

A photo taken from the Lebanese side of the northern border crossing of Al-Arida shows Syrian fighters assisting with the passage of Syrians back into their country on December 10, 2024. (AFP)

In Europe, home to at least 4.5 million Syrian refugees, several countries — including Austria, France, The Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, Greece, and the UK — announced they had halted Syrian asylum applications just hours after Assad’s fall.

Germany, which is home to the continent’s largest Syrian diaspora, was one of the first European countries to respond.

Nancy Faeser, Germany’s interior minister, said in a statement on Monday that the current “volatile situation” in Syria is the reason her country’s migration authority has paused asylum decisions, leaving thousands of Syrian applicants in limbo.

Austria has gone a step further, announcing plans to deport Syrian migrants. Interior Minister Gerhard Karner told Austrian media he has “instructed the ministry to prepare an orderly return and deportation program to Syria.

In The Netherlands, the government said it would stop assessing applications for six months. However, many are concerned it may also begin deportations.

Members of the Syrian community wave Syrian flags as celebrate on December 8, 2024 in Berlin, Germany. (AFP)

Discussions about sending refugees back to Syria amid such uncertainty have left many Syrians anxious about their future. This is particularly concerning for those who have built lives and established roots in their host countries.

Anti-refugee discourse has become increasingly common since the height of the European refugee crisis in 2015, when around 5.2 million people from conflict zones across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East arrived on European shores.

For many governments in Europe, the fall of the Assad regime could offer just the opportunity they were waiting for to show they are addressing public concerns about migration by removing thousands of Syrians.

But until Syria’s security situation stabilizes and its political future under its new de facto leadership becomes clearer, forced returns may be premature — or could even break international laws against refoulement should returnees come to harm.

Indeed, with the country still divided among rival factions, extremist groups like Daesh still at large, infrastructure in ruins, an economy crippled by sanctions, and uncertainty over the political agenda of the victorious HTS, Syria is by no means guaranteed peace and security.