ROME: Although Sudan has been in the throes of political turmoil since authoritarian leader Omar Al-Bashir was toppled in 2019, the sudden explosion of violence that began on April 15 appeared to catch the world by surprise.

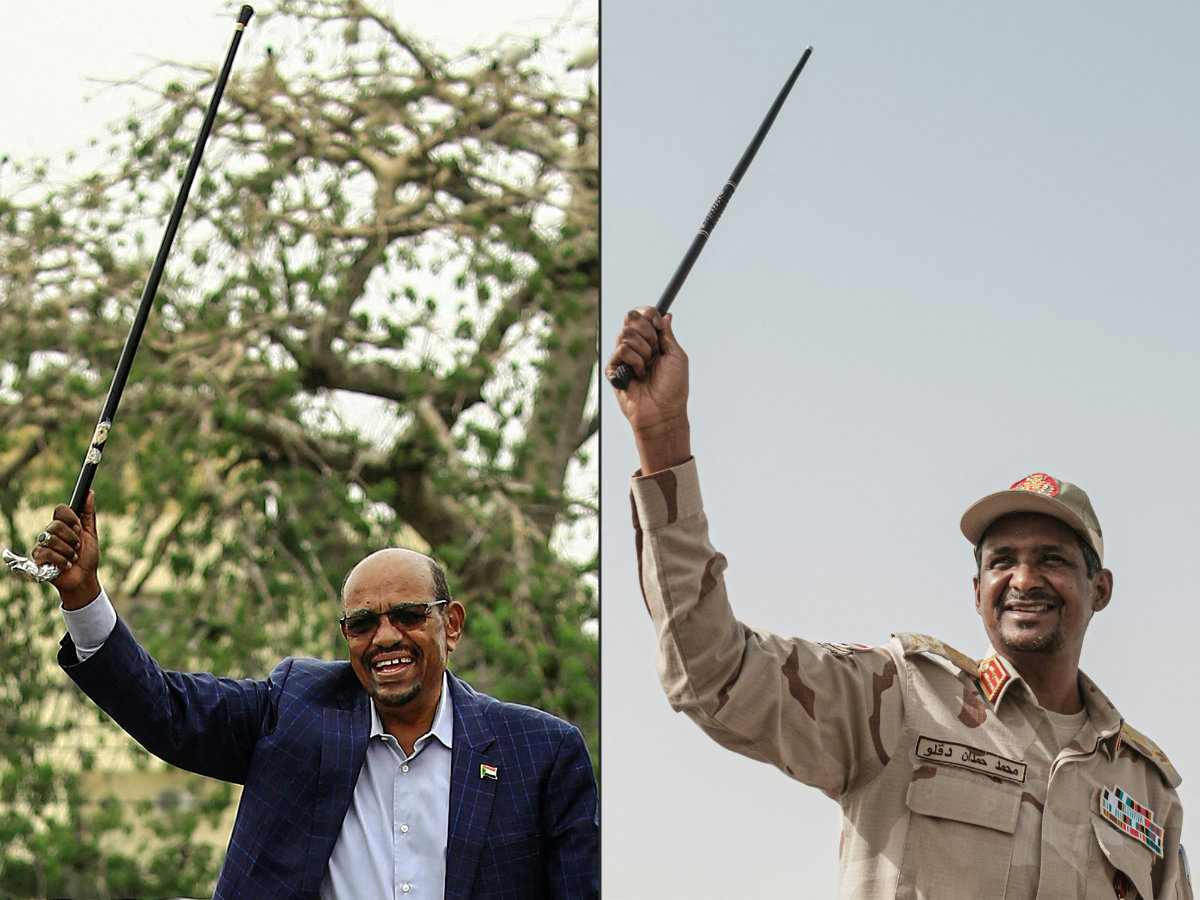

Explosions and gunfire in the capital Khartoum and elsewhere across the country, in defiance of repeated attempts to broker a cease-fire, have forced nations to hastily extract embassy staff and citizens who were at risk of being caught in the crossfire.

However, for many Sudanese citizens now forced to decide whether to remain in their homes, deprived of basic utilities, with food and medicine dwindling, or risk their lives by taking one of the increasingly lawless roads out of the country, signs of the coming crisis were all too clear.

Clashes between the Sudanese Armed Forces, led by the country’s de-facto ruler General Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, and a paramilitary group, the Rapid Support Forces, led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti, stem from plans to incorporate the latter into the regular army.

Tensions between the two men over the plan, which formed part of the democratic transition framework, had been growing for months, yet many in the international community appeared to have failed to sense the depth of their mutual mistrust — and were consequently blindsided.

Gen. Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, ;eft, and his archrival, Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo. (AFP photos)

“This is the worst of worst-case scenarios,” Volker Perthes, the UN special representative to Sudan, told colleagues during a virtual meeting shortly after the violence began. “We tried even with last-ditch diplomacy ... and we have failed.”

Sudanese fighter jets have continued to pound paramilitary positions in Khartoum in recent days, while deadly fighting and looting have flared in the troubled Darfur region, despite the army and the RSF agreeing to extend a cease-fire deal.

More than 75,000 people have fled their homes to escape the fighting, according to the UN’s International Organization for Migration, while tens of thousands have crossed into neighboring countries including Chad, Egypt, Ethiopia and South Sudan.

Many Sudanese say that foreign powers and international aid agencies should have been far better prepared for the likelihood of the feud between the two generals escalating into armed conflict and for the consequent humanitarian emergency.

“Hemedti and Al-Burhan are ready to fight to the death,” said Sudanese political cartoonist and writer Khalid Albaih.

Albaih, who has performed advocacy work for artists and creatives in Sudan, believes Sudanese could sense in recent months that the situation was reaching a breaking point.

Khalid Albaih

“Everyone saw it coming. Everyone knew something was going to happen soon,” he told Arab News. “The army was building defenses and the janjaweed leader (Hemedti) was moving into the city. You could feel the tension. There was no money in the country except for the money in Hemedti’s hands.”

Albaih calls what is happening now a “delayed war.”

“The international aid organizations were moving forward, pitting the two together more for stability in the country than for actual democracy,” he said.

“This is what is unsettling. We (the Sudanese public) have been fighting for peace for years and still we haven’t found a seat at the table. It seems like the message was to get a gun and you’ll get a seat at the table.”

Sudanese pro-democracy activists had been demonstrating for the reinstatement of Abdalla Hamdok, the prime minister ousted in the October 2021 military coup, to no avail. (AFP file)

The counterargument of course is that there were no “early warning” signs of a dramatic and violent falling-out. Proponents of this theory say that while an escalation was always a possibility — perhaps inevitable even — the international community was completely wrong-footed by the scale and ferocity of the feud.

“I think the criticism is misplaced,” Martin Plaut, senior research fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, told Arab News. “Yes, there was tension between Al-Burhan and Hemedti, but it could have gone on for another 18 months and just fizzled out, or it could have exploded, and it exploded. But you can’t predict when that’s going to happen.”

Martin Plaut

The real problem, said Plaut, “is that Hemedti had forces large enough to counter the Sudanese army directly, and the army was aware of this. As the African saying goes, you can’t have two balls in the field. The monopoly of force, which is supposed to be the right of the army, was just no longer going to hold.”

However, at least one prominent diplomat has acknowledged that foreign powers might have contributed to the crisis by bestowing legitimacy on both Al-Burhan and Hemedti, while turning a blind eye to their obvious antipathy toward one another and their reluctance to cooperate.

In an op-ed for The Washington Post, Jeffrey Feltman, the former US special envoy for the Horn of Africa, called the conflict “sadly predictable” given the West’s willingness to pander to both Sudanese strongmen.

Jeffrey Feltman

“We avoided exacting consequences for repeated acts of impunity that might have otherwise forced a change in calculus,” he wrote. “Instead, we reflexively appeased and accommodated the two warlords. We considered ourselves pragmatic. Hindsight suggests wishful thinking to be a more accurate description.”

Both Al-Burhan and Hemedti began their careers in the killing fields of Darfur, where a tribal rebellion descended into ethnic cleansing during the early 2000s.

ohamed Hamdan Daglo (Hemeti), right, rose from the ranks of the Janjaweed militia that figured in former strongman Omar Al-Bashir's ethnic cleansing campaign in southern Darfur about 20 years ago. (AFP photos)

After the fall of Al-Bashir in 2019, following months of unrest, the country had been on the path to a democratic transition. The process was derailed in 2021, however, when Al-Burhan and Hemedti joined forces to mount a coup against the transitional government of Abdalla Hamdok.

Although a new UN- and US-backed framework was eventually hammered out in late 2022 to facilitate a transition to civilian rule and implement security reform, many felt that a showdown between Al-Burhan and Hemedti was inevitable.

Indeed, their relationship evidently had turned into bitter animosity, culminating in violent clashes that now threaten to escalate into full-blown civil war.

Sudan's former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok (right), together with Generals Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan (middle) and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (left) during a deal-signing ceremony in Khartoum to restore the transition to civilian rule . (AFP)

In a scathing oped last week in the Wall Street Journal, the American columnist Walter Russell Mead, pointing out that Sudan has a history of 17 attempted coups, two civil wars and a genocidal conflict since independence in 1956, said: “A blind hamster has a better chance of building a nuclear submarine than the State Department had of orchestrating a democratic transition in Khartoum.”

The question for the international community now is whether it bears some moral responsibility for the diplomatic efforts that in hindsight strengthened the hands of both Al-Burhan and Hemedti, and for failing to prioritize peace building and conflict resolution when it had the chance.

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

The general consensus seems to be that as the Western-led economic and political order fades in the Middle East and Africa, actors such as Al-Burhan and Hemedti should be seen as who they are: powerful regional commanders interested in seizing economic opportunities and entrenching themselves, not aspiring democrats eager to share power with civil society.

Meanwhile, the World Food Programme has given warning that the violence could plunge millions more into hunger in Sudan, a country where 15 million people — one third of the population — already need aid to stave off famine.

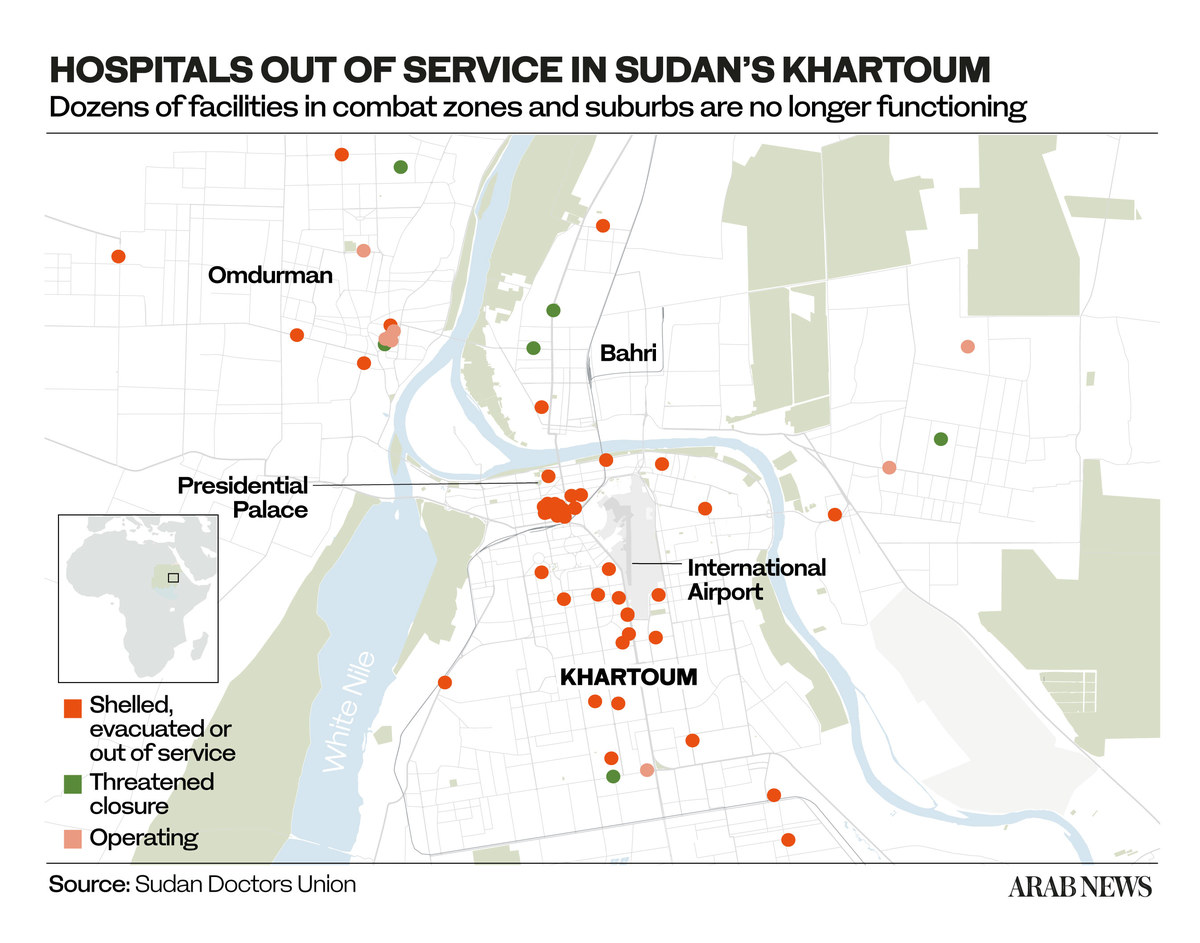

At least 528 people had been killed and 4,599 wounded in the fighting as of April 30, according to health ministry figures, although the real toll is likely far higher. The Sudanese doctors’ union has given warning that the collapse of the health care system is “imminent.”

Appeals by UN chief Antonio Guterres to the two warring Sudanese generals to “put the interests of their people front and center, and silence the guns,” have gone unheeded so far.