CAIRO: More than 1 million Palestinian refugees have found their last refuge in Rafah, Gaza’s southernmost city on the Egyptian border, where they grimly await a widely expected Israeli offensive against Hamas holdouts in the area.

Meanwhile, thousands of Palestinians, many of them with the help of family members already outside Gaza, have managed to cross the border into Egypt, where they remain in a state of limbo, wondering if they will ever return home.

For its part, the Egyptian government faces the prospect of a mass influx of Palestinians from Gaza into Sinai should Israel ignore international appeals to drop its plan to strike Hamas commanders in Rafah.

Egyptians had been sympathetic to the plight of Palestinians, despite their own economic woes. (AFP)

Although the Egyptian public is sympathetic to the Palestinian plight, shouldering the responsibility of hosting refugees from Gaza is fraught with security implications and economic costs, thereby posing a difficult dilemma.

Furthermore, despite taking in refugees from Sudan, Yemen and Syria, the Egyptian government has been cautious about permitting an influx of Palestinians, as officials fear the expulsion of Gazans would destroy any possibility of a future Palestinian state.

“Egypt has reaffirmed and is reiterating its vehement rejection of the forced displacement of the Palestinians and their transfer to Egyptian lands in Sinai,” Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, the Egyptian president, told a peace summit in Cairo last November.

Egypt's President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi (C) and regional and some Western leaders pose for a family picture during the International Peace Summit near Cairo on October 21, 2023, amid fighting between Israel and the Palestinian group Hamas. (Egyptian Presidency handout photo/AFP)

Such a plan would “mark the last gasp in the liquidation of the Palestinian cause, shatter the dream of an independent Palestinian state, and squander the struggle of the Palestinian people and that of the Arab and Islamic peoples over the course of the Palestinian cause that has endured for 75 years,” he added.

Additionally, if Palestinians now living in Rafah are uprooted by an Israeli military offensive, Egypt would be left to carry the burden of a massive humanitarian crisis, at a time when the country is confronting daunting economic challenges.

Seen on a large screen, Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi (R) welcomes Palestinian Authority President Mahmud Abbas to the International 'Summit for Peace' near Cairo on October 21, 2023. (AFP)

Although Egypt earlier this year landed its largest foreign investment from the UAE, totaling some $35 billion, experts believe that the economic crisis is far from over, with public debt in 2023 totaling more than 90 percent of gross domestic product and the local currency falling 38 percent against the dollar.

Salma Hussein, a senior researcher in economy and public policies in Egypt, believes Egypt is not in the clear yet.

“We are slightly covered but we will need more money flowing in and bigger investments,” she told Arab News. “We also have large sums of debt we need to pay back. The IMF pretty much recycled our debt and we have interest rates to cover.

“In times of political instability, we see a lot of dollars leaving the country in both legal and illegal ways. This happened in 2022 and it also happened during the last presidential elections in 2023.

“I think the same thing will happen again now due to what’s happening in the region. This is all a loss of capital which can affect us.”

Displaced Palestinian children chat with an Egyptian soldier standing guard behind the fence between Egypt and Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip on April 26, 2024. (AFP)

She is confident foreign assistance will be offered. And although the cost of hosting refugees will be high, there are many economic benefits to be had from absorbing another population — even for the Arab world’s most populous country.

“Egypt is too big to fail,” said Hussein. “There will be a bailout of its economy when it’s in deep trouble. And while investments and loans might not turn into prosperity, they will at least keep the country afloat. This is where we are now.

“As for the presence of a growing number of Palestinian refugees, I don’t think any country in the world had its economy damaged by accepting refugees. On the contrary, it might actually benefit from a new workforce, from educated young people, and from wealthy people who are able to relocate their money to their country of residence.”

FASTFACTS

• 1.1 million+ Palestinians who have sought refuge in Rafah from fighting elsewhere in Gaza.

• 14 Children among 18 killed in Israeli strikes on Rafah on April 20.

• 34,000 Total death toll of Palestinians in Israel-Hamas war since Oct. 7, 2023.

However, it is not just the economic consequences of a Palestinians influx that is unnerving Egyptian officials. This wave of refugees would likely include a substantial number of Hamas members, who might go on to fuel local support for the Muslim Brotherhood.

Hamas shares strong ideological links with the Muslim Brotherhood, which briefly controlled Egypt under the presidency of Mohamed Morsi in 2012-13 and has since been outlawed.

Since Morsi was forced from power, the country has been targeted by Islamist groups, which have launched attacks on Egyptian military bases in the Sinai Peninsula. The government is concerned that these Islamist groups could recruit among displaced Palestinians.

In this photo taken on July 4, 2014, Egyptian supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood movement gather in Cairo mark the first anniversary of the ouster of president Mohamed Morsi. Egyptian authorities are wary of an influx of Palestinian refugees into Egyptian territory as some of them could be Hamas extremists allied with the Brotherhood movement. (AFP/File photo)

The decision might be out of Egypt’s hands, however. Several members of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-wing coalition government have publicly called for the displacement and transfer of Palestinians in Gaza into neighboring countries.

Israel’s finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, previously said that the departure of the Palestinians would make way for “Israelis to make the desert bloom” — meaning the land’s reoccupation by Israeli settlers.

Itamar Ben-Gvir, Israel’s minister of security, also said: “We yelled and we warned, if we don’t want another Oct. 7, we need to return home and control the land.”

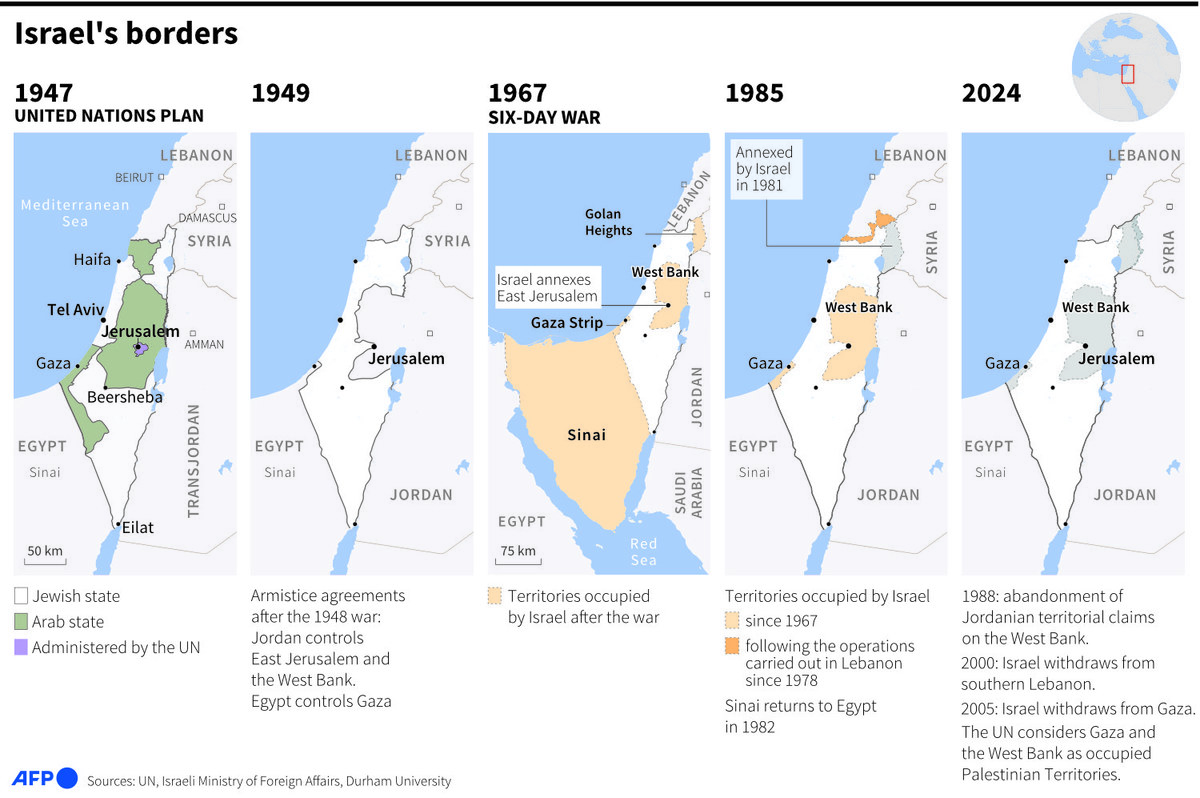

Maps showing the changes in Israel's borders since 1947. ( AFP)

Up to 100,000 Palestinians live in Egypt, many of them survivors of the Nakba of 1948 and their descendants. Their numbers steadily rose when Gamal Abdel Nasser came into power in 1954 and permitted Palestinians to live and work in the country.

However, matters changed after the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. Palestinians became foreign nationals, excluded from state services and no longer granted the automatic right to residency.

The precise number of Palestinians who have arrived in Egypt since the Gaza war began after Oct. 7 has not been officially recorded.

Palestinians and dual nationality holders fleeing from Gaza arrive on the Egyptian side of the Rafah border crossing with the Gaza Strip on December 5, 2023, amid an Israeli offensive on the Palestinian enclave. (AFP)

Those who have made it to Egypt, where they are hosted by sympathetic Egyptian families, fear they will be permanently displaced if Israel does not allow them back into Gaza. Many now struggle financially, having lost their homes and livelihoods during the war.

For host families, this act of charity is an additional burden on their own stretched finances. “We feel for the Palestinians but our hands are tied,” one Egyptian host in Cairo, who asked to remain anonymous, told Arab News.

“I am struggling financially myself, but I cannot bring myself to ask for rent from a man who lost his entire family and now lives with his sole surviving daughters.”

On the Egyptian side of the Rafah border crossing, trucks carrying aid and consumer goods are idling in queues stretching for miles, waiting for Israeli forces to permit entry and the distribution of vital cargo.

Many of the Egyptian truckers waiting at the border are paid to do so by the state. “We get salaries from the government and they provide us with basic food and water as we wait here,” one driver told Arab News on condition of anonymity.

Trucks with humanitarian aid wait to enter the Palestinian side of Rafah on the Egyptian border with the Gaza Strip. (AFP)

Israel has been limiting the flow of aid into Gaza since the war began, leading to shortages of essentials in the embattled enclave. Although Israel and Washington say the amount of aid permitted to enter has increased, UN agencies claim it is still well below what is needed.

Meanwhile, the truck drivers are forced to wait, many of them sleeping in their cabs or carrying makeshift beds with them. “I’d do this with or without a salary,” the trucker said. “Those are our brothers and sisters who are starving and dying.”

With events in Gaza out of their control, all Egyptians feel they can do is help in whatever small way they can — and hope that the war ends soon without a Palestinian exodus.

“It is unfathomable to me that we are carrying life-saving equipment and food literally just hours away from a people subjected to a genocide, and there are yet no orders to enter Gaza through the border,” the truck driver said.

“It shames me. I park here and I wait, and continue to wait. I will not leave until I unburden this load, which has become a moral duty now more than anything.”