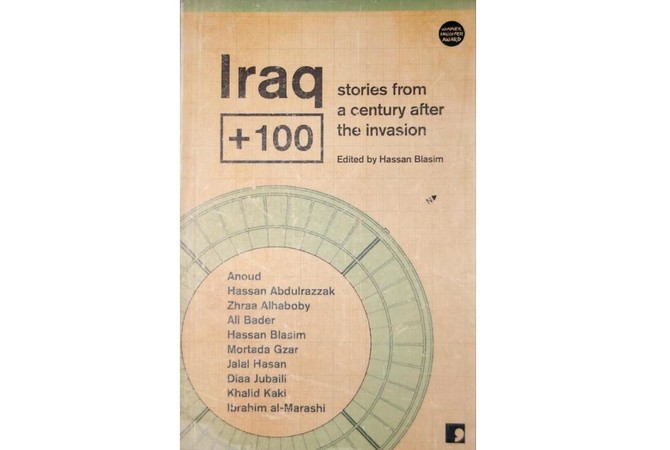

“Iraq + 100: Stories from a century after the invasion” is a collection of short science fiction stories by 10 Iraqi authors. The authors, some of whom live in Iraq and some of whom live abroad, imagine what the country will be like in the year 2103.

Edited by Hassan Blasim and originally suggested by Blasim’s publisher, Ra Page, the idea first came up in 2003 as a way to deal with the US invasion of Iraq. Considering science fiction stories are not common in the Arab world, Blasim wrote to many authors to convince them to write a futuristic story based on his belief that “writing about the future would give them the space to breathe outside the narrow confines of today’s reality.”

Blasim received a multitude of stories, in both Arabic and English, which he compiled to create this book.

Many stories stem from oppression, religious fanaticism and capitalist nightmares. Most of the tales are heartbreaking in their own way, as they lay bare the injustice that has riddled Iraq. One such story is titled “Kahramana” by an author called Anoud. The story is set in Sulaymaniyah and centers on Kahramana, who has been coerced into a forced marriage but flees to an international court in the hope that she will be allowed asylum elsewhere. Crowds rally behind her, but as her case takes years, and goes through its own ups and downs, the crowds begin to dwindle and the attention she once received disappears. The story exposes the futility of support and highlights the notion that crowds will rally until time and patience run out, leaving the victims to be forgotten.

This experience is not limited to one country, it is a worldwide tragedy and sadly repeats itself when humans become desensitized to the loss of life.

Creativity and imagination play an important role in the collection as authors such as Blasim, Hassan Abdulrazzak, Mortada Gzar and Khalid Kaki delve into advanced technological visions of Iraq. In “The Gardens of Babylon,” written by Blasim and translated by Johnathon Wright, Babylon is a playground for “virus architects and software artists.” Water is scarce but the Chinese have established a system to counter environmental shortcomings. In Kaki’s story, “Operation Daniel,” translated by Adam Talib, the past is frowned upon and ancient languages and literature are prohibited. Powerful overlords such as Gao Dong, who renames Kirkuk “Gao’s Flame,” believe that citizens are their beneficiaries and must “protect the state’s present from the threat of the past.” In Abdulrazzak’s story, “Kuszib,” life has changed entirely and no semblance of the old world exists.

The authors in this book do not shy away from bleak visions of the future, visions that have arisen from the destructive political and environmental policies of current-day Iraq. Climate change, depleting natural resources and rampant poverty cause the characters to yearn for a time before political struggle tainted the lives of Iraq’s inhabitants. “The Corporal,” written by Ali Bader and translated by Elisabeth Jaquette, is one such story. A fallen Iraqi soldier comes back to the world to tell future Iraqis who he was. He tells whoever will listen that he was born in 1960, served in the Iraqi army for 22 years, faced war for most of his time on earth and died for reasons misunderstood. It highlights the limited opportunities people ravaged by war have when it comes to choosing their own destiny.

Diaa Jubaili, Zhraa Al-Haboby, Jalal Hassan and Ibrahim Al-Marashi focus on futures in which citizens speak of the past and refuse to forget it. There is a particular longing for peace and tranquility in their stories, especially in “The Here and Now Prison,” written by Hassan and translated by Max Weiss. This theme is also prevalent in “Baghdad Syndrome,” written by Al-Haboby and translated by Emre Bennett, in which the older characters still refer to streets by their old names, still dream of Baghdad and revel in a beautiful past.

Each author touches upon Iraq’s tragic history and its bleak future. The destruction of the environment plays as important a role as the destruction of the country. Powerful overlords, authoritarian regimes and the continued limitation of life and freedom are presented in nearly every story, revealing powerful insight into the visions these creative talents have of Iraq’s future. However, a longing for the past keeps hope alive in the stories and allows the reader to revel in a past unknown to them, one that is not forgotten and one that will be carried through time, despite war and invasion. The memories of human life and history cannot be taken away as long as they are written about and remembered and this compilation is a testament to the hope that resides in remembrance, creativity and imagination.

Book Review: A testament to creativity and imagination

Book Review: A testament to creativity and imagination

What We Are Reading Today: Little Bosses Everywhere by Bridget Read

In “Little Bosses Everywhere,” journalist Bridget Read tells the gripping story of multilevel marketing in full for the first time.

“Little Bosses Everywhere” exposes the deceptions of direct-selling companies that make their profit not off customers but off their own sales force.

The book lays out an almost prosecutorial case against many multilevel marketing schemes, explaining why regulators need to take the industry seriously, and the larger story it tells about whom the economy has set up to fail.

The book “reads like a thriller as it investigates the birth and growth of this shadowy and sprawling industry that polished up door-to-door sales with a new veneer of all-American entrepreneurialism,” said a review in The New York Times.

The book primarily focuses on a broader analysis of pyramid schemes and their history.

What We Are Reading Today: ‘King Leopold’s Ghostwriter’

Author: Andrew Fitzmaurice

Eminent jurist, Oxford professor, advocate to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Travers Twiss (1809–1897) was a model establishment figure in Victorian Britain, and a close collaborator of Prince Metternich, the architect of the Concert of Europe.

Yet Twiss’s life was defined by two events that threatened to undermine the order that he had so stoutly defended: a notorious social scandal and the creation of the Congo Free State.

In “King Leopold’s Ghostwriter,” Andrew Fitzmaurice tells the incredible story of a man who, driven by personal events that transformed him from a reactionary to a reformer, rewrote and liberalized international law—yet did so in service of the most brutal regime of the colonial era.

In an elaborate deception, Twiss and Pharaïlde van Lynseele, a Belgian prostitute, sought to reinvent her as a woman of suitably noble birth to be his wife. Their subterfuge collapsed when another former client publicly denounced van Lynseele.

Book Review: ‘Oil Leaders’ by Dr. Ibrahim Al-Muhanna

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Muhanna’s book, “Oil Leaders: An Insider’s Account of Four Decades of Saudi Arabia and OPEC’s Global Energy Policy,” offers a detailed narrative of the oil industry’s evolution from a Saudi perspective, drawing on the author’s four decades of experience.

Published in 2022, the book coincides with global energy crises triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Al-Muhanna relies on data from OPEC, the International Energy Agency and interviews to provide an anecdotal biography of key figures who shaped oil politics, targeting a broad audience including policymakers, researchers and industry professionals.

The book is divided into 11 chapters, beginning with the influential role of Saudi Oil Minister Ahmed Zaki Yamani, whose overconfidence and perceived indispensability are critically examined.

Subsequent chapters highlight other pivotal figures, such as Hisham Nazer, Yamani’s successor, and delve into events such as the 1991 Gulf War.

The narrative also covers Luis Giusti, of Venezuela’s PDVSA, whose disregard for OPEC quotas sparked tensions, and discusses OPEC’s struggles with production cuts and falling oil prices in the late 1990s, which led to economic crises in oil-exporting nations such as Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.

Al-Muhanna explores the political ramifications of oil price fluctuations, noting how high prices influenced US presidential elections and shaped diplomatic interactions, such as George W. Bush’s visit to Riyadh.

The book also examines the rise of Russia under Vladimir Putin, the privatization of Saudi Aramco as part of Vision 2030, and the roles of contemporary leaders such as Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman and former US President Joe Biden in shaping global energy policy.

What We Are Reading Today: ‘Africa’s Buildings’ by Itohan I. Osayimwse

Between the 19th century and today, colonial officials, collectors, and anthropologists dismembered African buildings and dispersed their parts to museums in Europe and the United States.

Most of these artifacts were cataloged as ornamental art objects, which erased their intended functions, and the removal of these objects often had catastrophic consequences for the original structures.

“Africa’s Buildings” traces the history of the collection and distribution of African architectural fragments, documenting the brutality of the colonial regimes that looted Africa’s buildings.

What We Are Reading Today: ‘Birds at Rest’ by Roger Pasquier

“Birds at Rest” is the first book to give a full picture of how birds rest, roost, and sleep, a vital part of their lives.

It features new science that can measure what is happening in a bird’s brain over the course of a night or when it has flown to another hemisphere, as well as still-valuable observations by legendary naturalists such as John James Audubon, Alfred Russel Wallace, and Theodore Roosevelt. Much of what they saw and what ornithologists are studying today can be observed and enjoyed by any birder.